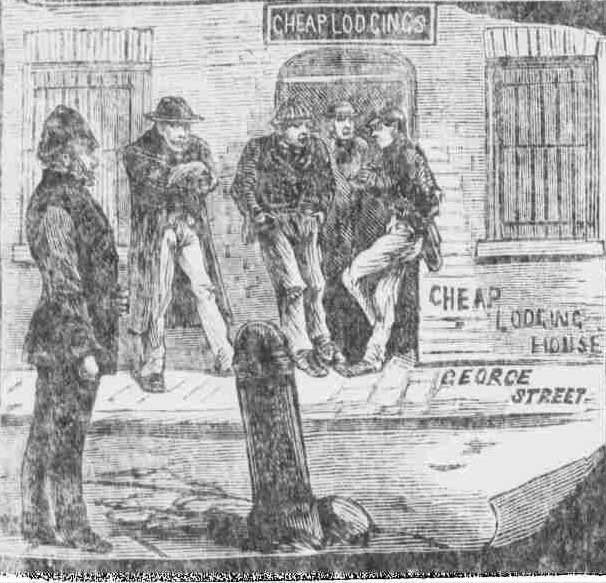

One of the things that all the victims of Jack the Ripper shared in common was the fact that, in almost all their cases – Mary Kelly being the exception – they lodged in the common lodging houses of Spitalfields and Whitechapel.

These places came in for a lot of press criticism during the period in the autumn of 1888, when the plight of the victims exposed the living conditions that prevailed inside many of them.

Indeed, there were times, in the immediate aftermath of several of the murders, when the police seem to have believed that the perpetrator of the crimes was hiding out amongst the transient population that inhabited the neighbourhood’s lodging houses.

IN A COMMON LODGING HOUSE

On Tuesday, May 1st, 1888, The Star, Guernsey had published an article, which was reproduced from the previous weeks Cassell’s Saturday Journal which gave readers an insight into what daily life was like in these establishments, and which provided a sneak peek at some of the characters who inhabited them:-

“To thoroughly understand what the common lodging houses are, you must see one.

Come down this narrow, unswept, and under the-weather looking street.

You see that house which looks as though it were a double-fronted shop with the shutters still up.

That is a common lodging house.

The door in the centre is a swing door.

Outside it a gentleman in the unpicturesque tatters of our national costume is smoking a clay pipe; and, with his hands thrust in his trousers pockets, is looking fixedly at nothing.

Over the doorway at which the gentleman stands, is an inscription in white letters on a black board, “Registered Lodging House. Beds 3d. and 4d. a night.”

INSIDE THE COMMON LODGING HOUSE

Let us push the swing door open and walk in.

It is broad daylight outside, but directly we have passed the swing door we find ourselves almost in darkness.

The room we are in is the “kitchen,” or common room, in which all the guests sit and take their meals, and amuse themselves until it is time to go upstairs to bed.

I cannot say how one of these kitchens would look in the glare of day. There is nothing to show sunbeams that they would be hospitably received, and so they remain outside. The light in these kitchens, then, is generally of the dim and religious order.

It suits the scene.

THE PEOPLE WHO LODGE WITHIN

The people who are sitting on the long forms at the tables, or crouching together before the dull red fire, would, some of them, look hideous in the full light of day.

In the red glow that the fire throws on them, as they sit in the darkened room, they look almost picturesque.

The swarthy fellow with the coal-black hair and the fierce eyes who sits on the floor, still working at his trade and making baskets, might in this light have stepped out of a Spanish picture.

The woman who, with a wretchedly dirty baby, sits on a form looking at him, is his wife.

They are having a few words together as we enter the kitchen.

They are tramps, and are only passing through London on their way to the south of England. The man had a cart and horse once; he did a broom and basket trade after the gipsy fashion.

HAWKERS AND STREET TRADERS

On the form drawn near the fire are three men of the hawker or street-trading profession.

These men have sold out their wares, and won’t go out again till early morning when they will be off to the markets by four o’clock in order to get a bargain.

They trade in different things according to the seasons of the year, but generally in the “scourings” of the market – that is to say, in the stuff which is not good enough for the shops, and even too bad for the costermonger with a connection. Fish, oranges, watercress, nuts, onions, apples – anything and everything that comes in their way at a price they will buy and sell.

THE WORKMEN WHO LODGE

The workmen who live in these lodging houses are not home yet.

They will come in about six o’clock.

There will not be many in the house because it is a low house – that is to say, it is a house frequented by tramps and loafers and shady customers, and moreover it is a “family house,” and that means women and children to disturb the harmony of the evening in the common kitchen.

The common lodging house is to these men home and club combined, and the proprietor who gets this class of men – men in steady employment – tries to please them, and gradually they fill the house, and then he excludes chance customers and “roughs,” and his house becomes a regular working man’s home.

ARISTOCRATS OF THE ABYSS

One great advantage that a man with regular wages finds in these places is that he is able to keep a valet.

Yes, a valet!

In all of those common lodging houses there are men who, for a copper or so a week, “valet” for the aristocrats.

For twopence a week paid to a poorer fellow-lodger, the aristocrat has his boots blacked and his supper cooked, in addition to this the valet runs his master’s errands and keeps his favourite seat by the fire till he wants it, and when there is a discussion on any matter the faithful valet chimes in with his master, and is always ready to back him up in any assertion that he may choose to make.

THE WRECKAGE OF HUMANITY

Besides working men and hawkers and tramps and mendicants, there is a class which frequent these common lodging houses which can only be properly described as wreckage.

It is among the wreckage that we find the “life drama” in its most painted aspect.

“Wreckage” forms a large percentage in the sum total of London misery.

Everywhere the men who have had their chance and flung it away jostle the men who have failed to grasp their chance, or who have had no chance at all; all classes meet in the common lodging house, and the workhouses.”