By the end of September 1888, the East End of London, as a whole, was beginning to calm down from the panic and excitement that had followed the murder of Annie Chapman on the 8th of September 1888.

Towards the end of September, a journalist from the Daily News took an evening stroll through the streets of Whitechapel and Spitalfields.

Arriving in Hanbury Street – where Annie Chapman had been murdered just a few weeks before – he was surprised by the general mood of the people and by how little alarm there appeared to be in the neighbourhood as a whole.

Accordingly, he stopped a respectably-looking elderly man, and commented on the fact that, “there seems to be little apprehension of further mischief by this assassin at large.”

The man simply smiled at him and replied, “No, very little. People, most of ’em, think he’s gone to Gateshead”.

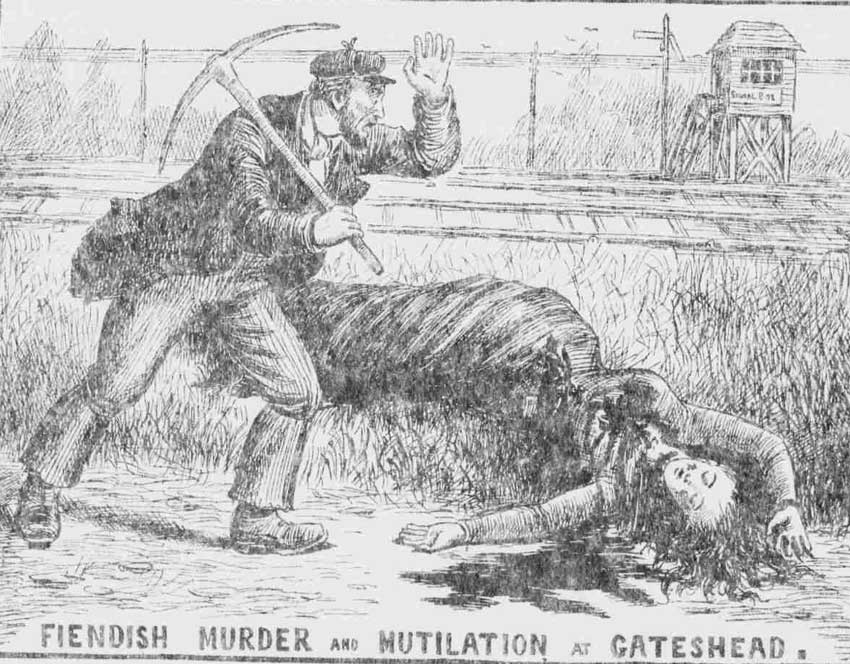

THE BIRTLEY FELL MURDER

The man was making reference to the murder of Jane Beadmore – which was much like the series of Whitechapel murders in its gruesome barbarity – that had taken place in Birtley, a small mining village, just to the south of Gateshead, in County Durham, in the north of England, on the 22nd of September 1888.

THE VICTIM AND A SUSPECT

The body of Jane Beadmore, who was also known as Jane Savage on account of her mother having remarried, had been found on the morning of Sunday 23rd of September 1888.

However, unlike the Whietchapel murders, the police very soon had a suspect in the form of William Waddell, who, up until shortly before the murder, had been her “sweetheart”; and who had not been seen in the locality since the discovery of the body.

IMITATING WHITECHAPEL MURDERS.

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper presented a full account of the events surrounding this northern atrocity in its edition of the 30th of September 1888.

The article read:-

“A tragedy, in some of its details strongly resembling the circumstances associated with the Whitechapel murders, took place at Birtley, county Durham, early on Sunday morning, the victim being a young woman, named Jane Savage, 26 years of age, and single.

On Saturday [22nd of September] she left her home to go to Newcastle, for the purpose, she said, of consulting a doctor, as she was unwell.

It is stated that she was suffering from an affection of the heart.

She returned about three o’clock in the afternoon, and soon after she left the house, stating that she was going to visit some friends, who live in a detached cottage some 200 yards from her parents’ house.

HER LAST KNOWN MOVEMENTS

At that house she stayed until about seven o’clock in the evening, and then went to the Mount Moor public-house, which is kept by a man of the name of Morris.

The public-house is at Birtley North Side, and the unfortunate woman was alone when she visited it.

As far as can be ascertained, a bottle of lemonade was all she had to drink.

After leaving Morris’s house, she went to a shop and purchased some sweets. This would be about half-past eight.

She was seen alive for the last time about that hour by a man who noticed her walking towards what is known as the Cube, near Vale pit, in a direction entirely opposite to that in which her home lay.

HER BODY IS FOUND

The road along which she was walking is a public road, and at one point it crosses a level crossing on the waggon-way running from the pits of the Birtley Colliery company to Pelaw main, and a short distance down this waggon-way, off the road between Birtley and Eighton banks, the body of the poor woman was found horribly butchered, between seven and half-past seven on Sunday morning [23rd of September 1888], by a mechanic who was proceeding to Ouston colliery for the purpose of repairing an engine at Ouston banks.

THE POLICE ARRIVE

The man informed Police-constable Dodds of the murder, and a closer examination of the surrounding circumstances was then made.

The body lay in a ditch beside the waggon-way, at a spot three-quarters of a mile or thereabouts distant from the unhappy creature’s home.

Life had apparently been extinct for some hours.

The hands were held upwards towards the face, as if she had been endeavouring to protect herself. Her clothes were disarranged, and the lower part of the body was exposed.

NO SIGNS OF A STRUGGLE

There was no sign of a struggle having taken place.

There were no bloodstains near the spot where the discovery was made, but the clothes on the body were literally saturated with blood.

The police-constable had the body removed to the house of the woman’s parents.

THE POST MORTEM

The medical examination which followed revealed wounds of a frightful nature.

On the right cheek there was a wound extending to the neck, and on the left side of the neck, a little below the ear, was an incised wound extending backward and downward. These were what may be termed minor wounds when compared with the condition of the lower part of the body.

From the lower portion of the abdomen there was a large incised wound extending upwards for several inches, opening the body.

All the wounds had been inflicted with a knife or some other sharp instrument.

ROBBERY NOT THE MOTIVE

The murdered woman, it is known, had little if any money upon her, and that which she had on Saturday night, together with a portion of the sweets she had bought, was found in the pocket of her dress.

A SHARP BLADE

The immediate cause of Jane Savage’s death appears to have been a deep incised wound in the left cheek.

The instrument used must have been long and sharp, and it entered the left cheek just below the ear. The wound extended almost right through; the neck, and the spinal cord was completely severed. This would have in itself been more than sufficient to cause death.

There was a wound also upon the other side of the face.

The injury to the lower part of the body had been terribly cruel.

The knife, or whatever instrument was used, had evidently been forcibly thrust into the body, and the half-severed bones showed the force that had been used to extend the wound.

DR PHILLIPS ARRIVES FROM WHITECHAPEL

Dr. Phillips, who made the post-mortem examination of the body of Annie Chapman, the victim of the last Whitechapel murder, was sent to Durham to examine the body of the murdered woman with the view of ascertaining whether the injuries inflicted on her resembled those inflicted on the Whitechapel victim.

Inspector Roots, of the Criminal Investigation department, also visited it.

THE INQUEST AND FUNERAL

Mr. Graham opened an inquest on Monday on the body of Savage.

After examining the body, and receiving evidence of identification, the inquiry was adjourned until Oct. 9.

The funeral of the deceased took place on Wednesday afternoon, in the presence of enormous crowds of persons, many of whom had travelled considerable distances.

The coffin bore the plain inscription:- “Jane Beetmoor [sic], died Sept. 22, 1888.”

It was followed to the grave by a cortege fully half-a-mile long, the interment taking place in the parish church at Birtley.

THEORY OF THE CRIME.

Telegraphing on Wednesday night, a correspondent said:-

“No arrest has yet been made. It seems to be the strong conviction of the police that the murder had been committed by some local man, not by any stranger, and for the present they are practically concentrating their efforts on the discovery of the man Waddle, a sweetheart of the deceased, who is missing.

His description has been widely circulated.

It is fair to say that beyond the coincidence of the disappearance of Waddle at the very time of the discovery of the murder there is not, so far as has yet transpired, any real evidence to connect the man with the crime.

It is supposed in some quarters that the woman may first of all have been attacked for another purpose altogether than murder, and that she successfully defended herself, and that thereupon the culprit was led to the perpetration of the abominable outrage.”

NOT THE SAME MURDERER

The belief that the murder had been carried out by the same perpetrator who had been responsible for the recent Whitechapel Murders was soon generally discounted in the locality where the crime had occurred, and most people were convinced that the murder had been carried out by her, now disappeared, “sweetheart” William Waddle, and that the motive had been the fact that she had found a new lover and had, therefore, spurned his advances.

Desperate to find him, the police issued a description of him which was published in several newspapers:-

“Age about 22 years, height 5 feet 9 inches, with a fresh complexion, with blue eyes, which are small and sunken, brown hair, figure proportionate, a very bad walker, last seen wearing a black and grey suit…”

ARRESTED ON THE FIRST OF OCTOBER

Despite initial fears that he might have committed suicide – to which end local disused mine shafts were searched – William Waddle was spotted on the road outside the town of Yetholme, on the morning of the 1st of October 1888 when, “looking wild and jaded and of altogether peculiar appearance,” he was recognised by a wool-dealer by the name of William Stenhouse, who escorted him to the local police station where he was arrested by Constable Thompson.

Thompson put him in a cell and bombarded him with questions before asking him if he knew Jane Beadmore.

Waddell replied that he didn’t.

Trying again, Thompson asked if he knew Jane Savage, to which Waddell replied, “That is my wife, I left her on Birtley Fell on Saturday.”

“Was she alive when you left her?” asked the policeman. “No, dead,” came the incriminating reply.

The next day, he was transferred by train to Gateshead, the track being lined by thousands of curious onlookers who hoped to get a glimpse of the accused.

HIS TRIAL AND DEATH SENTENCE

His trial opened at the Durham Assizes on Thursday November 29th 1889.

Despite a spirited defence from his barrister, Mr Skidmore, the jury, having retired to consider their verdict, took just 30 minutes to find him guilty.

Passing sentence, the Judge, Baron Pollock, warned him that there would be no chance of a reprieve:-

“After hearing the evidence against you in this case, and the verdict of the jury, I certainly cannot hold out any hope to you that the sentence which necessarily follows upon a crime of this character will be interfered with. I say this because I ask you most earnestly not to cling to any false hope that any change in that sentence may take place, and to occupy your thoughts and such time as is still left to you here by attending to the comfort and assistance which I have no doubt will be given you in directing your mind towards God in asking for pardon from him. To me it remains only to pass a sentence which alone the law awards to crimes such as yours, that is that you be taken from hence to the place from whence you came, and from thence to a place of execution, and that you be there hanged by the neck until you shall be dead, and that your body be afterwards buried within the precincts of the prison in which you were last confined after your conviction. And may the Lord have mercy on your soul.”

EXECUTED 18th DECEMBER 1888

William Waddell was hanged at a little after 8am on the morning of the 18th of December 1888.

Of course, the belief that the Birtley murder of Jane Beadmore had been carried out by the same hand as that which ended the lives of the Whitechapel victims had long been dismissed as a possibility.

Indeed, on the very day that Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper published its article on the crime, the East End murderer had struck in the early hours of that morning, 30th of September 1888,and had claimed two more victims, Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes.

And, the sense of relief in the East End at the belief that the killer had moved on and, “gone to Gateshead”, was, as the double murder was to prove, totally wide of the mark.