In 1712 a tax was introduced which came to be referred to as “a tax on knowledge.”

The tax in question was, in fact a tax on newspapers, and it would prove extremely unpopular, particular amongst the radical thinkers of the age.

For the government of the day the tax had to functions. Firstly, and, perhaps, most obviously, it provided a valuable source of taxation revenue.

Secondly, it placed newspapers – and, therefore, the dissemination of news and knowledge – well out of the reach of the working classes.

Little by little, the tax rate was increased over the course of the 18th and early 19th centuries until, with the passing of the Stamp Act, in 1814, the tax was set at four pence a copy. This meant that a newspaper could cost around seven to eight pence a copy. And this in an age when the average wages for an ordinary working man were around fifteen to seventeen shillings a week.

In other words, it could cost more than half a weeks wages for workers to be able to afford a daily paper.

WAYS AROUND THE TAX

However, the working classes were not be so easily fobbed off and, such was their desire for news, and for knowledge, that they resorted to all manner of ruses to acquire them.

One method was to simply rent a paper from a news vendor for an hour or two. They could also pool their resources and, having clubbed together with their neighbours or workmates, but a newspaper that would then either be passed from contributor to contributor, or else could be read out loud by a literate member of the group in a public place, such as an inn or a tavern.

NEWSPAPERS DIDN’T LIKE IT

The tax proved equally unpopular with the newspaper proprietors, who realised that, if the tax were to be reduced, or even removed, that might sell more papers and thus increase their profits, and so they began campaigning for the abolition of Stamp Duty on newspapers.

In 1836, their campaign found Parliamentary support, and the tax was reduced to just one penny.

THE DUTY ABOLISHED IN 1855

Then, in 1855, the tax was abolished altogether and, for the first time in over 143 years, news and knowledge was no longer subject to the unpopular duty.

This inspired Mr. B. Hyam, a Manchester Tailor and cap maker, to compose a poem, which was duly published by his, now affordable, local paper on 30th June 1855.

Today the press, from duty free,

Appears on every side;

Whilst competition reigns around

And news is scattered wide.

A perfect flood of papers rise

Like breakers in the storm

Of every size – at every price

And every make and form.

A MARKET FOR SENSATIONALISM

Notwithstanding Mr Hyam’s poetic observation, the cost of newspapers came down dramatically, making them affordable for the literate, and semi-literate, working classes.

This, in turn, led to the appearance of a plethora of new papers all of which had to compete for readers. the competition amongst the newspapers was fierce, and it wasn’t long before they discovered a fact, which newspapers still adhere to today – SENSATIONALISM SELLS.

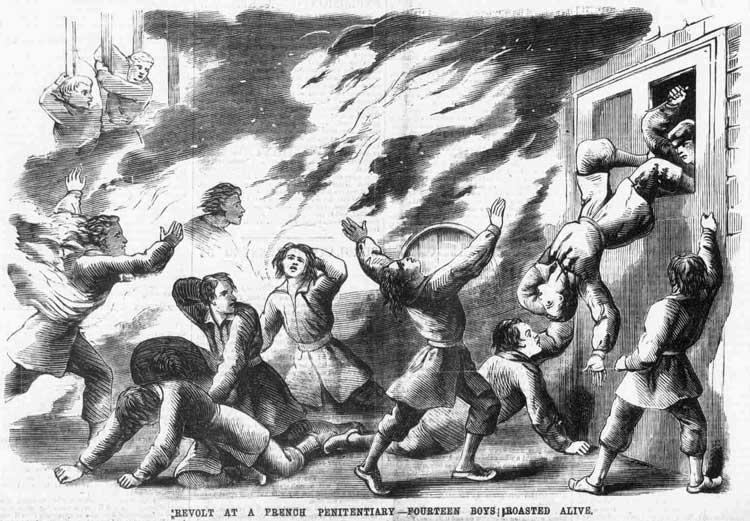

Crime reporting became popular, and the more gruesome or dramatic the case was, the more sales could be expected. Stories of sensational rescues at sea, or escaped zoo animals going on the rampage in major cities, appeared with increasing regularity. Articles about fires proved especially popular as papers tried to outdo one another in the sensationalist stakes in order to win readers.

These article were often accompanied by lurid illustrations that left little to the reader’s imagination, such as this one that appeared in the champion of sensationalist journalism the Illustrated Police News, in one of its earliest editions on Saturday 12th January, 1867.

THE PALL MALL GAZETTE

But another form of reporting came into vogue in the 1860’s, and one that would increase in popularity through the last 40 years of the 19th century and continue, unabated, into the early years of the 20th century.

On 7th February 1865, a new newspaper hit the newsstands – The Pall Mall Gazette.

Founded by George Murray Smith, its first editor was Frederick Greenwood (1830 – 1909).

Initially, the Gazette was very much a journal for gentlemen, a fact which it was emphatic about in a mission statement in its first edition:-

“We address ourselves to the higher circles of society: we care not to disown it – the Pall Mall Gazette is written by gentlemen for gentlemen; its conductors speak to the classes in which they live and were born. The field-preacher has his journal, the radical free-thinker has his journal: why should the Gentlemen of England be unrepresented in the Press?

A change of ownership in 1880 would lead to a change of stance to supporting the policies of the Liberal Party, and cause Greenwood’s resignation when he would be replaced by William Thomas Stead (1849 – 1912).

However, in its early incarnation the paper was aimed directly at gentlemen, or at least wannabe gentlemen, and, in consequence, it tried to come up with stories that would appeal to this readership.

A NIGHT IN A WORKHOUSE

Even in its early days, the Gazette was not above pulling the type of stunt that Stead would later become famous for.

In 1866 Frederick Greenwood persuaded his brother, James Greenwood (1831 – 1927), to undertake research for a new story on the poor of London.

The resultant article would give birth to a news style of journalism that would see more and more articles appearing on the poor of London, and other major cities around the country.

REPORTING THE LIVES OF THE POOR

Now, it must be said, that reporting on the everyday lives of the poor was not new. Charles Dickens (1812 – 1870) had done it; Henry Mayhew (1812 – 1887), Dickens great friend and co-participant in Dickens’s “Amateur Theatricals”, had done it in his monumental study London Labour and the London Poor, published in 1851.

However, Dickens, Mayhew, and other writers who had investigated the everyday lives of the poor had simply gone out and interviewed them and then published their resultant interviews.

But their accounts of the poor maintained a strong sense of “Victorian Propriety” – unpleasant issues were either glossed over, or else not mentioned, and poetic euphemism was employed to enable the genteel readers to read about the everyday horrors the poor had to face, without having to confront them head on.

A DIFFERENT APPROACH

What the Greenwood’s did was radically different.

James disguised himself as a vagrant, and checked in to spend a night in Lambeth Workhouse as one of the inmates.

A NIGHT IN THE WORKHOUSE

The subsequent article, published in 1866, as A Night In The Workhouse, caused an absolute sensation, confronting the reader in vivid, horrific detail with what went on behind the walls of a workhouse.

He told of people stripped of all their possessions, forced to bathe in water that had been used so many times that it had the consistency of a thick soup.

In one stomach-churning passage, Greenwood wrote how the mattress of the bed he was given was soaked in the blood of its previous inhabitant. On reporting the fact to the keeper, he received the sage advice, “just flip it over and you’ll be alright!”

Greenwood’s article gave birth to a new style of investigative reporter – one who would not only report on the conditions of the poor, but who would also go out and become one of them.

IT SOON CAUGHT ON

This style of reporting soon gained popularity and, by the 1880’s, there were so many journalists posing as down-and-outs whilst researching articles, that you can’t help but feel that one of the reasons the poor couldn’t get into the casual wards and workhouses was because so many journalists had got there first.

THE PEOPLE OF THE ABYSS

Nowadays the most famous example of this type of journalism is Jack London’s The People of The Abyss, but it should be remembered that London was at the end of a long line of reporters who had been queuing up to join the poor of London since the 1860’s.

The Greenwood’s pioneering articles, had two immediate effects.

Firstly, they sold copies of the Gazette.

Secondly, they gave the affluent classes an interest in the lives of the poor, and, as more and more newspapers began reporting on conditions in the slums, the middle and upper classes were suddenly confronted by a malcontent underclass that might, at any moment, rise up in revolution and, to quote, Margaret Harkness:-

“walk westwards, cutting throats, and hurling brickbats, until they are shot down by the military.”

Thus did the affluent classes come to look on the working classes a threat to ordered society – and by the 1880’s the lower classes were often being referred to as savages and we start to see articles that speak of missionaries being sent to almost convert people who dwelt on the doorstep of the wealthiest Square mile on earth.