A rich source of information about the police force that attempted to keep law and order in the Victorian metropolis is the number of memoirs that retired detectives wrote in which they spoke about their rise through the ranks of the Metropolitan Police.

These memoirs are interesting since, in the case of the memoirs of the likes of Sir Melville Macnaghten, they give us an insight into the theories and suspicions of various police officers as to who Jack the Ripper might have been.

Others are of interest in that they are able to give us an idea of the type of person that was recruited to the police force in the late 19th century, and of the process they had to pass through in order to become detectives.

They are also of interest in that several of these detectives spent time in their early careers policing the streets of Whitechapel and, as such, they provide us with an intriguing glimpse into the district through the eyes of individual officers, as opposed to through the eyes of the journalists who often saw the east End of London as a good place in which to mine sensational copy.

One interesting feature of the 19th century police recruitment policy was that the majority of the constables were, in fact, from outside London – farm labourers being a favoured group, as it was believed they would possess the necessary stamina to cope with the everyday rigours of life on the beat.

CORNISH OF THE YARD

One such officer was Ex-Superintendent George W. Cornish, who published his memoirs, entitled “Cornish of Scotland Yard” in 1934.

He begins his reminiscences by describing how, very early on in his career, he was assigned to Whitechapel.

This is what he says about his early recollections of his life in the Metropolitan Police:-

A THOROUGHLY BOVINE EXTERIOR

“At the beginning of February 1895, I walked into New Scotland Yard for the first time. I was on my way to my medical examination as a possible police recruit, and I remember hoping that my thoroughly bovine exterior hid my secret amazement at the difference between Westbury on a market day and London.

I was twenty-one, and it was the first time that I had been to London, or indeed far from my father’s farm.

After the examination by the Police Surgeon I was accepted as a recruit, and asked whether I wanted to go home again before commencing my training.

As I had only arrived in London that morning I could think of no reason why I should return to Wiltshire again that day, so I said that I was ready to start at once.

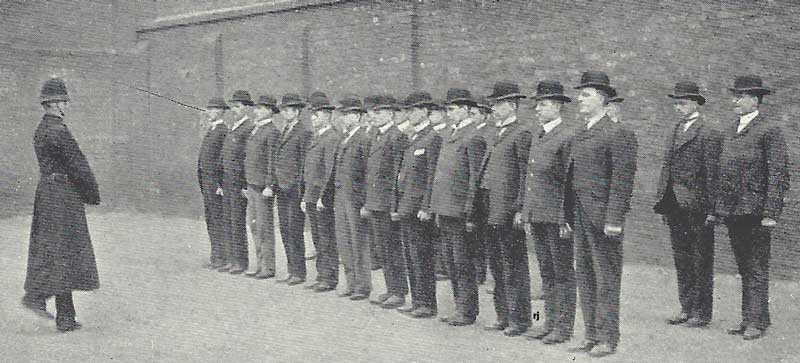

DRILLED AT WELLINGTON BARRACKS

The next morning found me trying to do my first drill at Wellington Barracks.

It was nearly a year before I saw my people and the farm again.

During the three weeks’ training which was the rule in those days, I lived with the other recruits in a Section House in Kennington. There were a number of other country lads there, and we spent our spare time in exploring London.

We were stolidly determined not to be bewildered by anything or anybody, but I think that we were all inwardly astonished at the crowded pavements, the endless streams of hansom cabs, horse busses and carriages.

Our days were so full of work that we had no time to be homesick, and for my own part the farm might never have existed, and Wiltshire seemed as remote as London had once been.

SWORN IN AND SENT TO WHITECHAPEL

At the end of the three weeks training I was sworn in before the Assistant Commissioner at Scotland Yard, given my uniform, and drafted to the Whitechapel Division.

This, as I realised later, was a piece of tremendous good fortune.

Of all the various districts to which I might have been sent, Whitechapel was undoubtedly the best in which to test the worth of a fledgling constable.

It certainly made a detective of me.

To-day the young policeman is given a period of training at Peel House. He starts with a thorough knowledge of the rudiments of his work, but we were thrown out to find our own feet. We were put in charge of an older and experienced constable and walked our beats with him. He taught us not only a great deal about our work and its pitfalls, the neighbourhood and the type of people who lived there, and when and where trouble usually started, but also what was of almost more use to us, the various peculiarities and idiosyncrasies of our immediate superiors.

MEAN STREETS AND DARK ALLEYS

To-day Whitechapel is as law-abiding as any district in London, and perhaps more so than some.

It is still cosmopolitan, and in parts rather picturesque.

The two great roads to the eastern suburbs and the Docks run through it, but they are very different from the cobbled, badly-lit streets of thirty-five years ago.

There are still mean streets and dark alleys, but the coming of busses and the Underground, restaurants, big shops and cinemas has altered it completely.

When I first went there the pavements were thronged by a hybrid crowd of Jews, dockers and sailors from almost every country on earth.

COMMON LODGING HOUSES

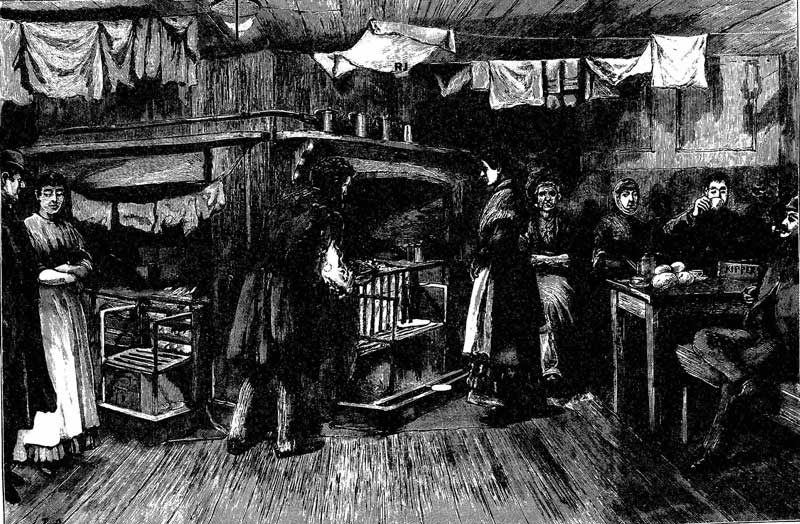

There were hundreds of low dens, public-houses of evil or notorious repute, and worse still, poor lodging-houses which were the breeding ground of every sort of crime.

Every type of criminal, both men and women, from the meanest sneak thieves and pickpockets to the smart crooks who worked further “up West,” lived in this human rabbit warren.

To make the work of the police still more difficult, these lodging-houses and dens were often linked together by cellars, and a network of courts and alleys which made raids extremely difficult, and escape easy.

Another difficulty was that of language; nearly half the people we had to deal with could speak very little English, and we had to use interpreters.

The condition of the lodging-houses even in my time was almost incredible, but before Mayhew published his book London Labour and London Poor, the conditions were beyond belief.

In 1851 the police had been given the task of supervising the London lodging-houses, but their work was more that of keeping an eye on criminal suspects than of any form of welfare work.

Even so, they shut seven hundred of the worst places before 1894 when the London County Council took over their control.

But the conditions were still appalling, and it was not until 1902, when the L.C.C. were granted additional powers from Parliament to make regulations and bye-laws, that things really improved.

CRIME HAD BECOME DIFFUSED

What applies to Whitechapel applies to other parts of London.

Increased transport, far more and far cheaper ways of amusement, and the various clubs and organisations for boys and girls have all played their part in doing away with these dens of vice and crime.

Crime has become diffused rather than lessened, and it is no longer concentrated in certain areas.

We had to deal with every type of crime known to the law.

There were constant gang warfare, fights that often ended fatally, and that form of blackmail which is known to-day as racketeering.

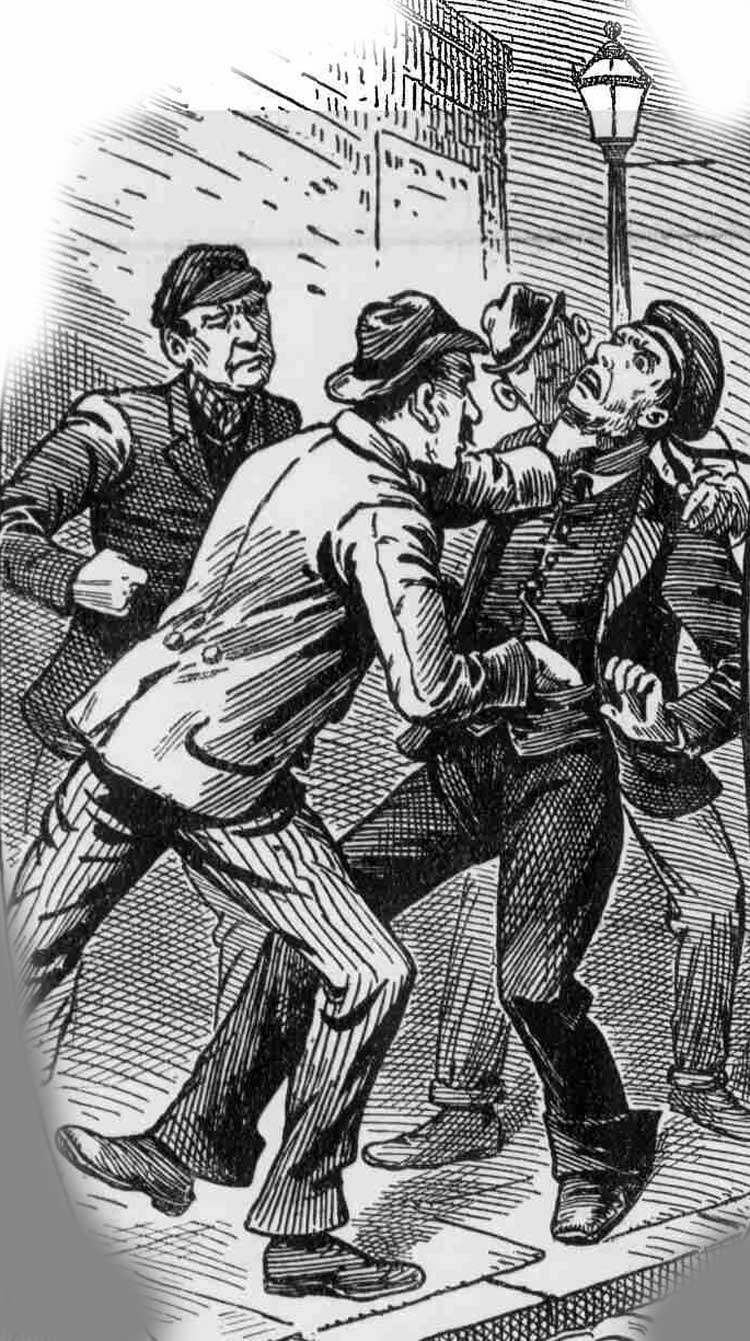

THE WHITECHAPEL GARROTTERS

One of the most prevalent crimes which we had to contend with when I was a young constable was garrotting or to use the legal explanation, highway robbery.

As the whole neighbourhood was cleaned up garrotting was almost stamped out, but it is a crime that has always existed and will always crop up again from time to time.

In a district so near the Docks sailors were naturally the best prey for these “gangs,” for when they came ashore after a long voyage they usually had plenty of money and were on the look out for a good time.

Women decoys lured them into public-houses, and when they were drunk, the men would set on them in some dark street, and rob them of everything of value.

The slightest show of resistance meant violence, and the man would be lucky if he got off with a beating from knuckle-dusters, broken bottles or some other similar weapon.

The sympathy of the crowd was usually with the gangsters when we made an arrest, especially if it happened to be a woman.

The men were often cowards, but the women fought like wild-cats, and a constable had to be a wary man when he tackled one of these furies if he knew that no assistance was within easy reach.

This happened to me once in my early days; after a struggle in which I was well scratched, I had arrested a woman only to discover that I had no idea where I was. I was forced to ask my way to the police station from a jeering and threatening crowd. It took me a long time to live down that joke.

Garrotting seemed a horrible crime to me, and I began to collect criminals rather as I had collected birds’ eggs as a small boy. I developed a “flair” for being on the spot when something happened, and I became so fascinated by my work that I spent most of my spare time in doing unofficial detective work in various places where useful information could be found.

THE EAST END GANGS

As I have already said, the various East End gangs caused us endless trouble.

Perhaps the only good thing about them was that they were constantly fighting among themselves which from one point of view assisted us in our work.

One of our difficulties was the abject fear of their victims, usually aliens or people who had broken or were breaking the law themselves in some way.

The Russian Jews with their ingrained terror of the police would in practically every case rather put up with the gangs than risk the consequences of complaining to the police.

This, of course, applied to the minor law-breakers who were blackmailed as well, and we were continually having to let cases drop through lack of evidence.

The usual procedure of these gangs is now familiar to everyone, they were “racketeers.” They levied a protection toll, or in other words they blackmailed timid alien shopkeepers, the proprietors of coffee stalls and so on.

The faintest shadow of protest on their part at this blackmail and the gang descended on them in force armed with guns, knives and such weapons as broken bottles. Their shops and stalls would be completely wrecked, and they themselves beaten up.

Only too often we arrived on the scene just too late to get the evidence we needed, but we might be in time to save some unfortunate man from being badly mutilated or even killed.

HOW DETECTIVES WERE TRAINED

By 1902 I had become a member of the Criminal Investigation Department of the Metropolitan Police, or briefly, one of the C.I.D.

It may perhaps be of interest to describe the process by which a detective is made.

The young constable is watched by his superior officers, and his general ability, his keenness, and his capacity for acting on his own initiative without making a fool of himself are noted.

Another important point is learning to give evidence.

A policeman who is unable to present his evidence clearly, or deal with and bring up witnesses in their proper and most useful order cannot hope for much success.

To-day the young constable learns the rudiments of police procedure and the methods of giving evidence at Peel House while he is training.

We did not get this opportunity, but we used to attend the police court twice a day to listen to cases and see how they were conducted.

After two years in uniform if the constable proves himself keen on his work and exceptionally efficient, the Divisional Detective-Inspector will, when the next vacancy occurs, ask him whether he would like to go in for this particular branch of police work.

Such was the method of becoming a detective when I was young.

A policeman’s, and for that matter, a detective’s career is a series of examinations, and they were not and are not easy.

In these days young policemen are given tuition in preparing for their first examinations, but thirty years ago we had to do it for ourselves. There were good libraries in the reading-rooms of the police stations where we could get all the textbooks we wanted on law and police procedure, but general education and general knowledge which form an important part of these examinations was another matter.

POLICE ACCOMMODATION AND EDUCATIONS

In the Section House, where I lived with about forty other men, many of us subscribed a shilling a week and paid a schoolmaster to come and give us evening lessons.

I had another job besides my police work when I was down at Whitechapel; I was the caterer to my Section House, and I kept the job for over six years.

This, perhaps, wants a word of explanation.

The unmarried policemen who live in the Section Houses cater for themselves. They choose one of their number who undertakes to find good cooks, and himself arranges for and supervises all the shopping. Each man pays so much a week as his mess bill. It naturally depends on the efficiency of the caterer whether the cooks are good at their work and do not spoil food in the cooking, also that the menu is varied.”