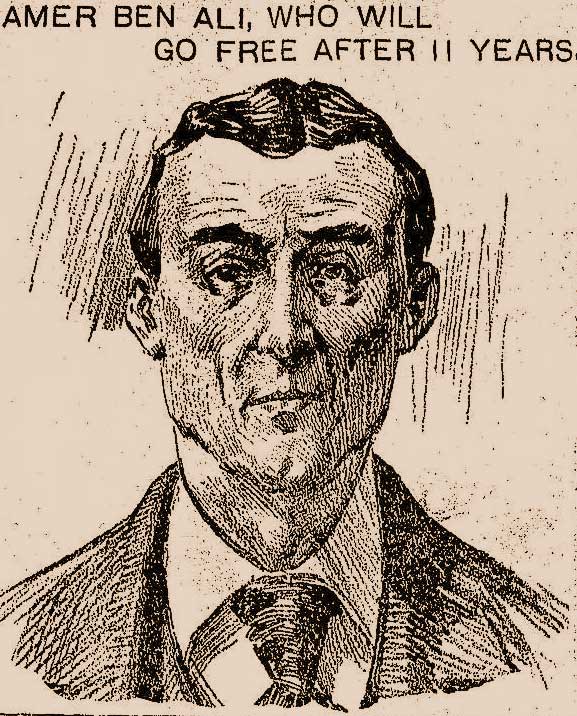

In July, 1891, Amer Ben Ali, also known as “Frenchy” was found guilty of the murder of Carrie Brown, which had taken place on the 24th of April, 1891, and had been sentenced to life in prison.

However, in 1902, the case against him was brought into question by new evidence; and the State Governor duly pardoned him of the crime.

The World published details of this new evidence in its edition of 17th of April, 1902:-

“FRENCHY” SET FREE AFTER 11 YEARS IN JAIL

Governor Odell, Acting on New Evidence, Gives Liberty to the Unfortunate Who Was Accused, of the Murder of “Old Shakespeare”

DOUBT OF HIS GUILT HAS EXISTED ALWAYS

The Crimes of “Jack the Ripper” In London Had Shocked Humanity, And New York Police Had Boasted Such A Monster Could Not Escape Here

After eleven, years of imprisonment Ben Ali, alias George Frank, alias “Frenchy,” convicted of the murder of “Old Shakespeare” in New York City has teen pardoned by Governor. Odell.

The Governor announced tonight that he had exercised Executive clemency in a long list of pardons, of which Frenchy’s was the last.

The Governor’s reasons for pardoning Frenchy were that there had always doubt as to the prisoner’s guilt, and that public sentiment at the time may have been a little too severe, owing’ to the crimes of the famous “Jack the Ripper” in London.

Frederic R. Coudert, of Coudert Bros., filed a petition for Frenchy’s release some time ago.

The French Consul has promised to have him transported at once.

He was transferred thirteen months ago from the Matteawan State Hospital for the insane to the Dannemora State Hospital.

MURDER A NOTED ONE AND TRIAL DRAMATIC

When Amer Ben-Ali was convicted of the murder of “Old Shakespeare”, almost everybody who heard all the evidence doubted his guilt. Even the twelve men in the Jury box doubted it, for if he was guilty at all, his crime was murder in the first degree. Their verdict was a certification of their doubt.

That doubt, which was strong, even amid the popular excitement, at the time of the trial, continued to grow stronger year by year, so that many efforts were made to have the prisoner Pardoned.

These all effected nothing until startling new evidence, first published exclusively in The World, was laid before Governor Odell.

Chiefly upon this, as well as upon a consideration 0f the weakness of the case for the prosecution, the Governor has pardoned the prisoner.

Carrie Brown, alias “Old Shakespeare”, was a drunken woman who lived precariously by vicr in the Whitechapel of New York, that squalid region in the neighbourhood of Water Street and Catharine Street, where stood theEast River Hotel.

The woman was sixty years old, withered and wrinkled, but with rouge on her cheeks.

Early in the morning of April 24th, 1891, she was found dead in a bed on the top floor of the East River Hotel. She had been strangled until life was extinct.

Then the assassin had mutilated her body in the manner made familiar to the public by the crimes of “Jack the Ripper”, who murdered women of Carrie Brown’s class in London’s. Whitechapel.

POLICE HAD MADE A BOAST

The “Jack the Ripper” murders in London. were, at the time, attracting the attention of the civilised world.

The New York police had jeered the clumsy efforts of the London police to catch the assassin.

“If we ever had a crime like that in New York,” they boasted, “we’d catch the murderer within twenty-four hours.

The time had come to make good on this promise.

Within twenty-four hours of the murder of Carrie Brown, the police, working under the direction of Inspector Byrnes, had two suspects looked up, and two or three more within easy striking distance, if they should determine to seize them.

The prisoner, whose individuality seemed best to fit this crime way Amer Ben Ali, a vagrant, who had haunted the district for months and who was called George Frank or “Frenchy” by the women who frequented the evil resorts.

“Old Shakespeare” was murdered by a degenerate.

Every circumstance of the crime proved this. “Frenchy” was a creature of such habits that one by one the dissolute women with whom he associated had turned against him. He had beaten them and robbed them of their scanty money. “Old Shakespeare” was the only one who would endure him.

FACTS THAT MADE MANY DOUBT

Furthermore, “Frenchy” was known to have occupied room No. 33 that night, which was diagonally across the hall from room No. 31, in which the woman was murdered.

True, she had gone to her room at 10.30 P. M. with a. man utterly unlike “Frenchy” and “Frenchy” did not enter the hotel until midnight; but the police argued that he went there determined to rob and murder the old woman, and waited until her companion left her.

It was not announced by the police for several days after the arrest that “Frenchy” was the murderer.

He was put on trial early in July 1901.

When the prisoner shuffled into court, he looked more like a wild animal than like a man. His black hair and beard were matted. His tiny black eyes had a wolfish glare. He was almost six feet in height, but his powerful shoulders were bent and his long, lean legs crooked at the knee. His arms were abnormally long. , With their gnarled and lengthy’ hands, whose knotty fingers ended in claw-like nails, they suggested the arms of a gorilla.

A dozen of the physical abnormalities enumerated by criminologists as stigmata of degeneracy were apparent in “Frenchy.”

MAN LOOKED LIKE A WILD ANIMAL

The man not only looked like a wild animal, but had as little chance to tell his story as would an ape accused of the crime.

First, they tried a French interpreter, who found that “Frenchy” had only a few French phrases at his command.

He said he was from the north of Africa, so an Arab cigar dealer named Sultan was brought in.

Even he could make out very little of what the prisoner said, for “Frenchy” was really a member of a Riff mountaineer tribe, one of the wild people who war on Arabs as well as the French soldiery in Algiers.

Never was there a more dramatic moment in the old General Session Court-House than when “Frenchy” leapt from the witness chair and, raising his long hands high above his head and gazing upward, uttered cries in his wild language – cries of prayer, of protection, of frenzied appeal.

“He calls to God and says he is innocent,” was the interpreter’s scanty and stolid rendering of that fervid plea.

But the case against the helpless outcast was too strong.

The police Central Office detectives told with great circumstantiality of finding a trail of blood leading from the room of the murder to “Frenchy’s room.”

Drop after drop they found along the hallway, then the print of a bloody hand on the knob of “Frenchy’s” door and marks on his bedclothes, as of one wiping off blood on

the blanket of his bed.

BLOOD TRAIL WAS A MYTH

Against this was the evidence that the murderer had washed his hands in an altogether different room; also the fact that the four chief newspapers of New York had sent out their best reporters on the case.

These men had searched that hallway with scrupulous care two hours before the Headquarters detectives arrived, and they were positive that there was not one blood drop in the

hallway.

Those telltale drops could have been placed there after the reporters visit, and still be in time for discovery by the men who wanted to convict “Frenchy.”

There was blood on the man’s shirt, for which he gave a reasonable account, but the police insisted that it came from the murdered woman.

The detectives had scraped under his fingernails and had found blood corpuscles.

CONVICTED ON SLENDER EVIDENCE

Upon this slender evidence, and upon his general bad character, “Frenchy” was convicted.

The police force was vindicated.

The popular feeling was, “He may not be guilty, but he’s better off in Auburn Prison than wandering around committing petty crimes.”

HE BROODED AND WROTE LETTERS

Amer Ben Ali brooded over his fate. He learned to speak and write English, after a fashion.

Every spark of his not abundant intelligence was concentrated on efforts to gain his freedom.

To his counsel, Friend and House, to various Governors of this state, and to newspapers, he wrote pitiful letters, begging for release.

They were in vain.

SENT TO AN ASYLUM

After two years in prison, constant brooding brought on melancholia.

“Frenchy” was sent to the asylum at Matteawan. He was returned to prison as cured in six months, but a year later he was again sent to the asylum.

M. Bruwaort, the French Consul in this city, as well as Ovide Robillard, a New York Lawyer, worked hard for his release, but he was still kept in prison.

ATTACKED HIS BEST FRIEND

On January 16th, 1898, “Frenchy” was seized with a fit of murderous frenzy, and he tried to kill William Green, his best friend, a boy who was sixteen years old.

A NEW WITNESS COMES FORWARD

Then, in May, 1901, George Damon, a New York businessman of the highest standing, came forward to make known a startling fact that he had hitherto kept secret through dread of publicity.

Mr. Damon had employed at his home in New Jersey a surly Dane, known only as “Frank”, who was missing during the night of the murder, and who came home at 6am in so ugly a mood that his fellow servants were afraid of him.”

SUPPRESSED EVIDENCE

It transpired that Mr. Damon had been keeping secret some major evidence that, had it been known at the time of the original trial, could have cleared “Frenchy” of the murder of Carried brown.

The New York Times, on Friday, 24th May, 1901, gave full details of an affidavit that this new important witness had sworn:-

TO SECURE RELEASE OF BEN ALI

“After stating how he came to employ on his place a laborer named “Frank,” whom he had secured from Castle Garden, relates how on the morning after the Shakespeare murder he went to his barn, and there was warned by one of his help not to go near the man “Frank,” as the latter had been out all night and was asleep, having acted exceedingly ugly.

Five or ten days afterwards, the affiant says, Frank left his employ, and upon sending a servant into the man’s room to clean it up, the girl returned bringing with her a key of an East River Hotel room, the place where the murder occurred, the number on the key being the same as that of the room in which the woman was killed.

Besides the key, a bloody shirt was found.

The affiant, according to the lawyer, then goes on to say that the man “Frank ” was apparently a sailor, and that he spoke broken English. He was of a sullen disposition, and altogether a dangerous customer to handle.

WHY HE DIDN’T COME FORWARD

The affidavit next explains why the affiant did not appear sooner, the reasons being that, in the first place, he disliked the publicity; in the second place, he feared that the man Frank might appear to take revenge on him, and finally, because he thought from what he heard of the suspect that a miserable old man of his description ought to be as happy in a prison, where he was well taken care of, as he would be out of it.

Also, he had come to the conclusion that “Frenchy” was a dangerous character and deserved to be locked up.”

THE MURDER WAS NEVER SOLVED

It appeared that a gross miscarriage of justice had been done to Amer Ben-Ali, and, in consequence, the Governor had acted and had pardoned him of the offence.

Which means that the murder of Carrie Brown was never traced, and, in consequence, the New York Police found themselves with an unsolved case, every bit as gruesome and as baffling as the Jack the Ripper case had been to their London counterparts.