Homelessness was a massive problem in London prior to and after the Jack the Ripper murders. There were numerous reports in newspapers throughout the 1880’s that brought to the attention of readers the plights of the rough sleepers who were forced to bed down on the streets of the Capital.

The following article was published in The Pall Mall Gazette on the 21st of September 1886:–

WHERE LONDON’S HOMELESS WANDERERS SLEEP

A NIGHT ON THE EMBANKMENT BY A MIDNIGHT WANDERER

“Big Ben chimes twelve. The harvest moon hangs in the pale night sky, and a cold east wind is blowing up the Thames. Cab after cab and hansom after hansom rush across Westminster Bridge; knots of men and women are assembled at the street-corners round Parliament-square, but on the Embankment it is growing very quiet.

As I enter the broad road into that great open dormitory, and slowly wander down to where the homeless and the poor are said to spend their nights, the noise of the town becomes stilled; and soon all that is left of it is a dull, heavy murmur, mixed with the rustling of the planes, the shadow of whose foliage in the moonshine falls as a coverlet of dark lace on the white flagstones.

ALONG THE EMBANKMENT

The seats arc empty ; the guests in this department of the open-air hotel have not yet arrived.

Down to the Needle not a human being is seen except four tall policemen wrapped in their unprofitable-looking capes.

Then we come to the lonely figure of a man, who has thrown himself down, and is breathing heavily as his head drops low on his chest and his arm falls over the side of the form.

Nearer Blackfriars Bridge the seats are more frequented.

SOME OF THE PEOPLE

In twos and threes the men sit together – some old, with yellow, wrinkled faces, white beards, and bent backs; others, middle-aged men, drunken and sulky-looking, men with vice and crime stamped on their faces; and slight, lanky lads, their ragged coats buttoned up to their throats, and their shoulders drawn up with cold and possibly with hunger. Most of them are talking, a few smoking, all regardless of the occasional presence of a “lady” among them.

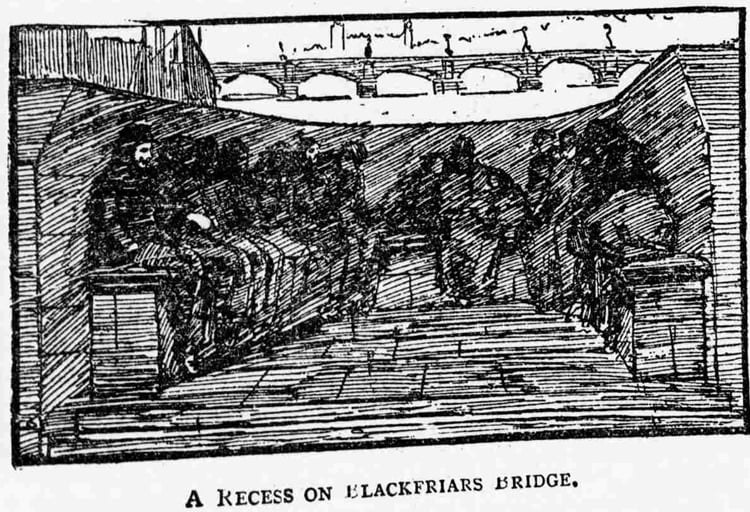

But of the latter there are few, and they sit silently and listlessly among the men: The hour is late, but the wing known as Blackfriars Bridge is occupied.

Seven men sit in the first niche, and one woman, under whose shawl a child, its head resting on the woman’s knee, is quietly asleep. She is of middle age, and out of the white handkerchief, which is tied over her ears, her face looks strangely dark and forbidding.

Gloomily she stares before her, heeding neither the men around her nor the passers by.

HUMAN FIGURES UNDER RAGS

In the three other recesses on the same side, which is least exposed to the wind, more men are sitting, leaning, crouching, in attitudes which make it impossible to discern the human figure under the rags.

Later it becomes more silent; and as I saunter back on the opposite side of the bridge I find,’an empty niche,’ where I sit down on the seat, comparing the wide stone bench to the narrow cushioned seats of one of our great railways, and deciding that a night on Blackfriars Bridge would be pleasanter than a night in a hot, dusty railway carriage.

But I have scarcely had time to calculate that a dozen men could easily be seated in the recess, when I am joined by two loiterers who sit down beside me.

They are a man and a young girl – he surly-looking and mute; she fresh and rosy, and open to a chat.

“These are cold quarters,” I venture to say, carelessly and amiably.

“Very cold for them poor coves what stop all the night. We ain’t going to do it; we only came out for a walk,” she says, coming closer, and smiling broadly and good-naturedly.

He, on being questioned, admits that he has spent many a night on “that ‘ere seat,” that it is “deuced cold,” and that he goes to work at four o’clock.

Then the two, who for this once are only amateur occupiers of the bridge, depart side by side, and I too resume my wanderings.

I have counted twenty-six sleepers on the bridge.

HOMELESS ON EMBANKMENT

Returning to the Embankment, I find that some of the dormitories are now well filled.

Shiveringly an old woman complains of the “dreadful cold” before she leans back among her male companions; some of the seats are crowded, and on some a whole compartment is taken up by one occupant, whose pillow is a small pile of newspaper.

Now and then one of the men gets up shivering with cold, and runs, his hands thrust into his pockets, up and down in front of a seat, keeping an eye on his share of it.

From under the arch of Waterloo Bridge there rises a heavy snore.

In the dark hole formed by the timber stationed under the arch another man is coughing a rough cough, which sounds the more terrible as it is mingled with the thin shrill whistling of the night wind, which gains in strength as it grows later.

DARK SHADOWS IN THE FURTHEST CORNER

Between Blackfriars and Waterloo Bridge there is an open space leading into Bouverie-street. It is enclosed by a temporary wooden wall, gay with the most cunning devices of London advertisers. The rickety gate leading to it stands ajar all day and night, and behind and all about this open space are scattered about heaps of stone and earth, half overgrown with grass and weeds.

Into this gate I enter, attracted by some dark shadows in the furthest corner – shadows which when approached become a ragged, dirty mass of humanity.

Against the wall, among the stones, on the damp grass and in the weeds, their heads are laid.

THEY ARE HERE EVERY NIGHT

Newspaper placards, the tatters of which flutter hither and thither, covered parts of their bodies, and still they lie, heeding no footsteps, no voice, not even the dazzling bull’s-eye which a City policeman, who has joined me, turns fully upon them.

“I can show you more of them; they are here every night,” he says, leading the way to another part of the enclosure.

There again they lie – not one, not two, but scores of them, huddled together like one immense mass of rags, a ghastly sight under the clear sky, and by the side of the proud mansions.

Once a young boy groans and stirs in his sleep as the glaring rays touch him, but he only turns away from the light and falls asleep once more.

WE NEVER DISTURB THEM

“We never disturb them,” says my newly acquired friend,” as long as they keep quiet. Poor devils! they have no place to go to; and night after night they come about midnight, and are off again with the daylight. There are fewer here to-night than I have seen for three months past; it must be the east wind which drives them away from the river. As soon as they begin to be noisy, or to make themselves objectionable in any way, they are sent off; but it is rarely that we have to do that.”

“Suppose several of the men get unruly, would it not be rather a hard task for you to master them single-handed?”

“No fear of that. I have only to throw my bull’s-eye along the Embankment (I can throw the light a mile in any direction) and shake it for a moment, and my mate is down here at once But the poor wretches don’t attempt anything of the kind, except when now and then a drunken fellow comes and squats down among them, and then they are only too glad to get rid of him.

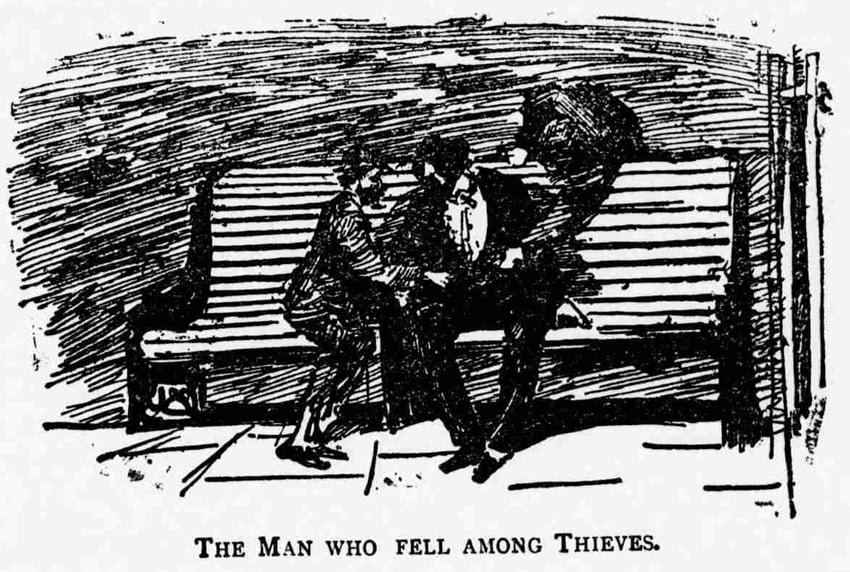

One other occasion when they are tempted to become unruly is when a drunken gent tumbles among them.

They are then not above doing a little in the pick-pocketing line, and the poor gent is almost sure to be minus watch and coin when he wakes up.”

With this the policeman turns round and I pursue my way back to St. Stephen’s, each little turret of which stands out clear and bold against the cloudless starry sky.

THE DRUNKEN GENT

Thirty-eight sleepers on the Embankment between Blackfriars and Waterloo Bridge have I passed; and now the identical “City gent” staggers along – a tall young man, walking, or rather balancing himself, on his toes, while his arms fight the air, and his shining hat comes lower down over his face at every jerk he gives.

Leaning on the parapet, two vicious-looking individuals follow his every movement, as onward he staggers.

Are they the hyenas of whom the constable has been telling just now?

Then the seats which I pass are empty. I have left the great dormitory, the Hotel de Dieu, in the true sense of the term.

THE MOST PITIFUL SIGHT

But no; something moves in the deep shade of the pyramid-shaped trees, whose leaves, seen in the bright daylight, are assuming the metallic tint which comes with early autumn, but which tonight are of the deepest black.

Alas! the most pitiful of the sights of the cold September night is reserved to the last.

An old, old woman rests on the seat; her head is covered with a black lace bonnet, which she has pushed forward over a sad, pinched face. A thin shawl over a thinner dress is all she has to keep the chill sir out; her trembling hand grasps the back of the seat, and shrinkingly she turns her head away and pretends to be asleep.

THE HEART OF WESTMINSTER

Parliament-street is empty; the Whitehall Horse Guards have closed the shutters of their narrow quarters, and one lonely red-coated soldier stalks up and down in front of the long row of Government offices.

Now one look at Trafalgar-square.

Save for a group of policemen standing about it is apparently deserted.

MORE HOMELESS PEOPLE

But no: on the seats and all along the stone step which runs along behind the fountain there are slight signs and sounds of life; and now, indeed, I see that every seat is closely packed with men and women, more respectable-looking than those I have encountered before, but all evidently settled for the night. And, behind them, under the grey wall from the one flight of steps across to the other, there is not a square foot of open space to be found.

Crowded closely together they lie; it is impossible to say whether they are old or young, for their faces are mostly covered with hats, handkerchiefs, or pieces of newspaper.

There are seventy-five of them, all counted, and twenty-five more have taken their position on the seats above in front of the National Gallery.

A hundred homeless creatures in Trafalgar-square, forty more on the Embankment between Westminster and Blackfriars, twenty-six on Blackfriars Bridge, and a policeman’s verdict that there are fewer tonight than there have been for the last three months – that is the result of one night’s ramble.

“Slumming” has gone out of fashion; but would it not be worth while for the ex-slummers to go out into the highways of London and to stretch out a helping hand to “some forlorn and shipwrecked brother” who spends his days in fruitless search for work, and his nights in bitter misery?”