On Thursday, 17th April, 1873, The Falkirk Herald published the following article, which was, in fact, reproduced from the London Daily News, that took readers on a heart-rending visit to one of the slum streets in the East End of London.

The article paid a visit to a house located in a St George’s-in-the-East, one of the most poverty-stricken districts in Victorian London, and it provided readers with a glimpse of the lives being led by the hard-working poor, for whom every day was a constant battle for survival.

They lived a hand-to-mouth, day-to-day, existence and just a small change fo circumstance – a day’s illness, or even a change in the laws governing or affecting their trades, for example – could send them spiralling deeper into poverty, at which point they would become dependent on charity, or, and very reluctantly in most cases, the local Workhouse.

The article read:-

LIFE IN THE SLUMS OF LONDON

“Here is a street in St George’s-in-the-East.

It contains about seventy, four-roomed houses, and the inhabitants average four to every room.

We enter one of the houses.

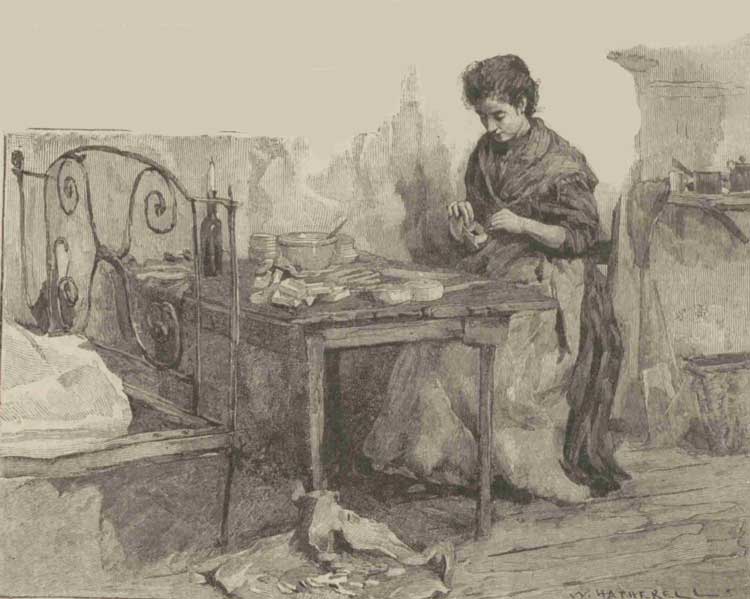

THE SLIPPER-MAKER

In the first room is slipper-maker. Her husband is dock labourer out of work. She makes the “uppers” of carpet slippers, sewing up the sides and binding the edges.

Her eldest girl helps her, and, between them, they make a dozen and half of these uppers a day by constant work.

The pay is 34d a dozen.

No wonder she is forced sometimes to take outdoor relief; and some help she gets from charity encourages rather than demoralises her.

THE POOR WIDOW

In another room is a poor widow with two children, a boy and girl – the boy eleven, the girl thirteen.

They were employed by a lucifer-match factory, and earned between them from three shillings to three and sixpence week; the mother got occasional work in washing.

The boy has broken down, and is ill of fever, and a neighbour, a slipper-maker from the room above, has brought her work down that she may watch him while his mother is away.

THE WORKHOUSE

The boy had been ill some time, and the mother had refused to degrade herself by letting him go to the workhouse.

The neighbours had, however, persuaded her to let him go, but she had been unable to live without him, and, ill as he was, had fetched him back.

The present regulations about infectious diseases were not then in force.

THE SKEWER MAKER

In yet another room of the same house was an old woman, miserably dressed, half leaning against, half sitting on her squalid truckle bed.

A table and broken chair were all her furniture.

There were on the mantlepiece a jug, a cracked tumbler, a teapot, and a cup without a saucer, but there was no fire in the grate.

On a shelf close to the fireplace was a bit of bread, a little packet containing perhaps an ounce of tea, and a parcel which looked like a quarter of a pound of brown sugar.

On the table were two strong knives and a whetstone, with some pieces of wood, such as might be picked up a carpenter’s yard: the floor was covered with chips.

Her occupation was that of making wooden skewers for dogs’ and cats’ meat; she got eightpence a thousand for them, and found her own wood.

THE DOG TAX

The news was just out that the dog tax would be rigidly enforced, and thousands of dogs would be destroyed.

She had tried to extend her trade by making butchers’ skewers, but the gipsies threatened to undersell her, and she was in despair, and was just making up her mind that she must come to the workhouse at last.

ILL-PAID FEMALE LABOUR

This is all in one house; but a like tale might be told of every house in the street, and in many a street.

There are many forms of ill-paid female labour.

The drapers have lately begun to sell hooks and eyes by the ounce, but this small change has sent to the workhouse many women who got a scanty living by sewing them on the cards on which they used to be sold.

Hundreds of women are employed by the penny toy makers, and a wretched living they earn.

The women who stitch together the pieces of gingham or alpaca which make the covers of umbrellas get 10d a dozen covers.

Those who sift the contents of our dust-bins, to find the valuables and save all the cinders for the use of brick burners, get about 10d day on the average for their work.

THOUSANDS OF LABOURING POOR

These and a score of other occupations are the means of living to thousands labouring people, and it is to these people that outdoor relief is so needful; they are the people whose occasional applications swell the ranks of outdoor pauperism, and it is those to whom charity may be wisely administered.”