Major Arthur George Frederick Griffiths (1838 – 1908) was the author of more than 60 books, the best known of which, as far as the public were concerned, were about sensational crime cases.

In 1901, he published Mysteries of Police and Crime, part of which, inevitably, dealt with the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.

It is more than apparent that he consulted Melville Macnaghten during his research for the book, since the passage that deals with the Whitechapel murders is almost verbatim what Macnaghten had written in his 1894 memorandum on the case.

The Northants Evening Telegraph, in its edition of Saturday, 9th March, 1901, reprinted an excerpt from the book and republished what Griffiths had written about the case, as well as his views on the success, or lack thereof, of the police in catching criminals:-

WHO WAS JACK THE RIPPER?

Those in search of sensational reading will find in Major Griffiths’ “Mysteries of Police and Crime,” now being published by Messrs Cassell and Co.

He says:-

The outside public may think that the identity of that miscreant “Jack the Ripper,” was never revealed.

So far as absolute knowledge goes, this is undoubtedly true.

THE THREE SUSPECTS

But the police, after the last murder, had brought their investigations to the point of strongly suspecting several persons, all them known to be homicidal lunatics, and against three of these, they held very plausible and reasonable grounds of suspicion.

Concerning two of them, the case was weak, although it was based on certain suggestive facts.

One was a Polish Jew, a known lunatic, who was at large in the district of Whitechapel at the time of the murders, and who, having developed homicidal tendencies, was afterwards confined in an asylum. This man was said to resemble the murderer by the one person who got a glimpse of him – the police constable in Mitre Court.

The second possible criminal was a Russian doctor, also insane, who had been a convict in both England and Siberia. This man was in the habit of carrying about surgical knives in his pockets; his antecedents were of the very worst type, and at the time of the Whitechapel murders he was in hiding, or, at least, his whereabouts were never exactly known.

The third person was of the same type, but the suspicion in his case was stronger, and there was reason to believe that his own friends entertained grave doubts about him. He also was a doctor in the prime of life, was believed to be insane or on the borderland of insanity, and he disappeared immediately after the last murder, that in Miller’s Court, on the 9th November, 1888. On the last day of that year, seven weeks later, his body was found floating in the Thames, and was said have been in the water a month.

The theory in this case was that after his last exploit, which was the most fiendish of all, his brain entirely gave way, and he became furiously insane and committed suicide.

SOMETHING HAPPENED TO JACK THE RIPPER

It is at least a strong presumption that “Jack the’ Ripper” died or was put under restraint after the Miller’s Court affair, which ended this series of crimes.

It would be interesting to know whether in this third case the man was left-handed or ambidextrous, both suggestions having been advanced by medical experts after viewing the victims.

It is true that other doctors disagreed on this point, which may be said to add another to the many instances in which medical evidence has been conflicting, not to say confusing.

LUCK AND DETECTION

Among the many outside aids to detection, “luck,” blind chance, takes a very prominent place.

When Charles Peace was taken at Blackheath in the act of burglary, and charged with wounding a policeman, no one suspected that this supposed half-caste mulatto, with his dyed, skin, was a murderer much wanted in another part of the country.

Every good police officer freely admits the assistance he has had from fortune.

A FEW EXAMPLES

One of these – famous, not to say notorious, for he fell into bad ways – described to how he was much thwarted and baffled in a certain case by his inability to come upon the person he was after, or any trace of him, and ho, meeting a strange face in the street, a sudden impulse prompted him to turn and follow it, with the satisfactory result that he was led straight to his desired goal.

The same officer confessed that, chancing to see a letter delivered by the postman at a certain door, he was tempted to become possessed of it, and did not hesitate to steal it. When he had opened, and read it, he found the clue of which he was in search!

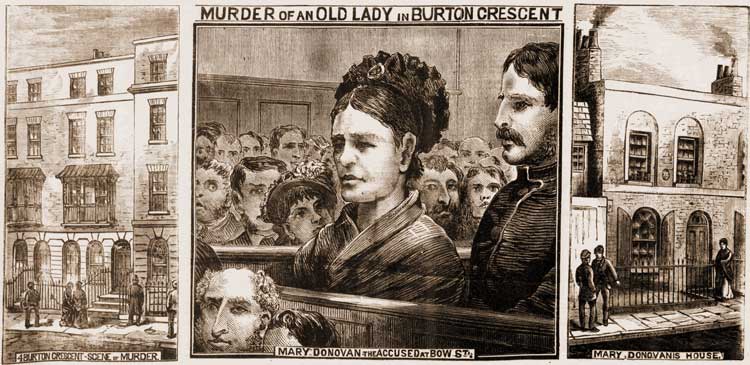

THE BURTON CRESCENT MURDER

The Burton Crescent murder, in December, 1878, must always be remembered against the police.

An aged widow named Samuel lived at a house in Burton Crescent, but she kept no servant on the premises, and took in a lodger, although she was of independent means.

The lodger was a musician in a theatrical orchestra, away most of the day, returning late to supper.

One evening, there was no supper, and no Mrs. Samuel, but making a search he found her dead body in the kitchen lying in a pool of blood.

The police summoned a doctor to view the corpse, and it was found that Mrs. Samuel had been battered to death with the fragment of a hat rail in which many pegs still remained.

The pocket of her dress had been cut off, and a pair of boots was missing, but no other property.

Nothing could have happened till late in the afternoon, as three workmen, against whom there was apparently suspicion, were in the house till then, and the maid who assisted in the household duties had left Mrs. Samuel alive and well at four pm.

Only one arrest was made, that of a woman, one Mary Donovan, who was frequently remanded on the application of the police, but against whom no sufficient evidence was forthcoming to warrant her committal for trial.

The Burton Crescent murder has remained mystery to this day.

THE MURDER OF LIEUTENANT ROPER

So has that of Lieutenant Roper, R E, who was murdered at Chatham on the 11th of February, 1881.

This young officer, who was going through the course of military engineering, was found lying dead at the bottom of the staircase leading to his quarters in Brompton Barracks. He had been shot with a revolver, the weapon, six-chambered, was picked up at a short distance from the body, one shot discharged, the remaining five barrels still loaded with ball cartridges.

The only presumption was that the murderer’s object was plunder, personal robbery.

A SHORT LEAVE OF ABSENCE

Mr. Roper had left the mess at an earlier hour than usual, between eight and nine, on the plea that he had letters to write home announcing his approaching arrival on short leave of absence.

A brother officer accompanied him part of the way to Brompton Barracks, but left him to attend some entertainment, Roper declining to go at once, for the reason given, but promising to join him later.

The unfortunate officer was quite unconscious when found: and although he survived some forty minutes, he never recovered the power of speech, so that he could give no indication to his assailant.

A poker belonging to Roper was found by his side, and it was inferred that he had entered his room before the attack, and had seized the poker as the only instrument of self-defence within reach.

NO CLUE EVER FOUND

Not the slightest clue was ever obtained which would help to solve this mystery; rewards were offered, but in vain, and the police had at last to confess themselves entirely baffled.

Mr Roper was an exceedingly promising young officer; he had but just completed his course of instruction with considerable credit, and he was said to have been in perfect health and spirits on the fatal evening, that there was nothing whatever to support, and indeed everything to discredit, any theory suicide.”