If there was one thing that the Jack the Ripper murders exposed, it was some of the shortcomings of the Metropolitan Police detective department that faced the onerous task of trying to hunt the perpetrator of the atrocities down.

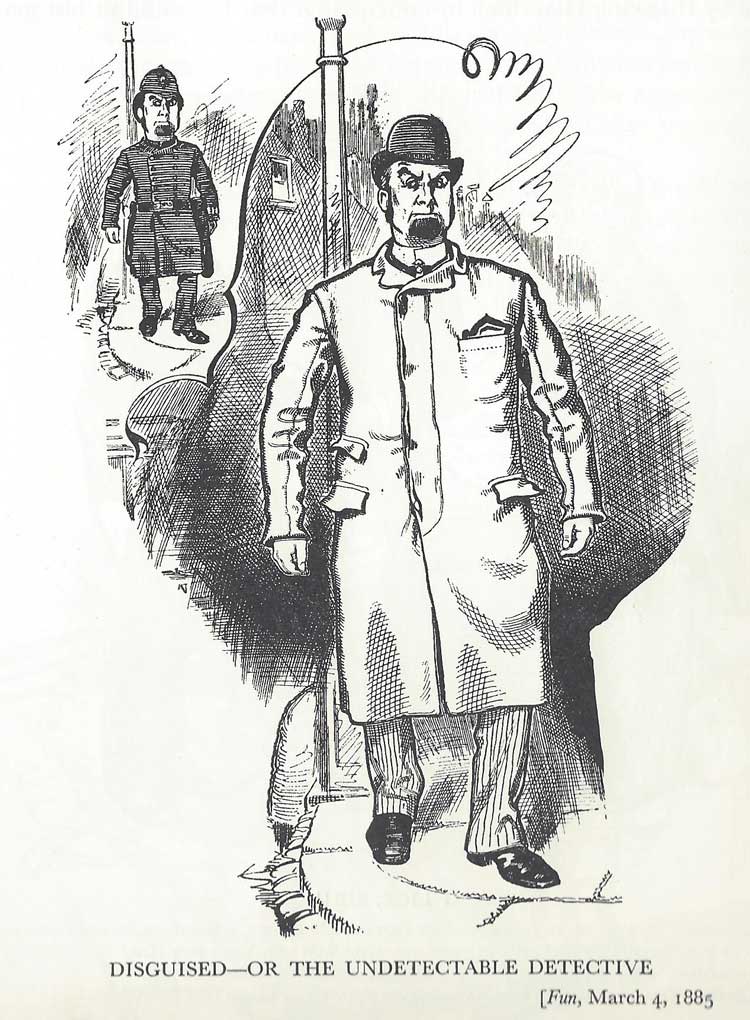

It must be said that the police – and in particular the plain-clothes men – had been the subject of jibes in the press for several years prior to 1888.

But, from early September 1888 there was a groundswell of criticism of the detectives from certain sections of the media, most noticeably from the radical press.

Whereas a great number of the press attacks on the police were both unfair and unjustified, it cannot be denied that, in some respects at least, Scotland Yard’s Criminal Investigation Department, showed itself to be lacking when it came to uncovering the identity of the Whitechapel Murderer.

As the murders increased, and the police showed themselves to be no closer to catching the miscreant responsible, the press criticism gained momentum, and even newspapers that had initially shown sympathy to the plight of the police began criticising the detectives and the shortcomings of the police force as a whole.

On Friday the 5th of October 1888, five days after the so-called “double event” that saw the murders of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes within an hour of each other, the St James’s Gazette published an article that cast a critical eye over the police force as a whole, and of the Criminal Investigation Department in particular:-

OUR DETECTIVE FORCE

“In one sense the machinery upon which we in this country rely for the detection of criminals may be said to be the most inscrutable thing ever invented by mortal man.

Official information as to its character there is none; and any attempt to gather information which can be depended on as even approximately accurate is almost certain to end in failure.

It is useless to apply direct to Scotland-yard.

If one interrogates an individual member of the detective force, the answer is that “the views of every one of us are known to the head authorities, and if you were to publish mine I should be ‘spotted’ instantly.”

The ordinary policeman does as he is bid and “knows nothing.”

All this secrecy would be justifiable if the detective force were really a secret police.

There would then be some excuse for concealing from mere idle curiosity the organisation and personnel of the system.

THE CRIMINALS ALL KNOW THE DETECTIVES

But, the fact is, that our London detectives are unknown only to those with whom they never have occasion to concern themselves.

Every thief in London knows a “tec” at first sight – if not by his face or even by his gait, certainly by his boots; for, incredible as it may appear, every “plain-clothes man” wears the square-toed, unseamed, regulation boots, and by that token is instantly recognised wherever he may be seen.

However, we, albeit not of the already instructed criminal class, have been able to penetrate to some extent into the mysteries of this department of the public service.

THE MAKE UP OF THE DETECTIVE DEPARTMENT

The whole detective force is under the control of the Director of Criminal Investigations.

Immediately under him there are “superintendents” of varying rank and authority.

Under these there are the divisional superintendents; and these in turn have under them inspectors, sergeants, and constables.

The whole of this force is recruited from the uniformed police.

Under an order made by Sir Charles Warren, no policeman is eligible for the position of a detective until he has served three years in uniform – an order admirably calculated to ensure that every detective shall have the appearance, gait, manner, and methods of an ordinary policeman.

HOW TO BECOME A DETECTIVE

Any policeman who wishes to become a detective must make due application.

If successful, he is taken out of uniform and put into plain clothes (except boots), and his pay is increased by the amount of what his uniform is estimated to have cost.

For all practical purposes he is now simply a police-man in plain clothes.

Certainly he has more freedom as to his movements, although he has to make minute reports of his proceedings; but in all other respects he has simply put off his uniform and put on the costume of the private citizen.

From this point his promotion to higher rank and pay depends on himself,

WHY BECOME A DETECTIVE?

And here we may answer the question which will naturally suggest itself: Why, seeing that the change from policeman to detective brings so little advantage, do so many policemen solicit the change?

The answer is, that every policeman believes he would be more successful – that is, he would be able to run more people in – if he were not in uniform.

The appearance of a blue coat at an incipient fight has a chilling effect on the combatants, and the same effect is produced on burglars, pickpockets, garrotters and the like; but the plainclothes man excites less suspicion, and he can (or so, at least, he supposes) look on while a beautiful “case” grows and develops under his very eyes.

Moreover, when an ordinary policeman has surprised and tackled a burglar, has struggled with him for a couple of hours, has sustained serious injuries, and has at length landed his man at the police station, the matter is ended so far as he is concerned.

It is the plain-clothes man who now comes in – “makes inquiries,” poses as the discoverer of “information received,” and finally carries off all the laurels.

These are the reasons why all policemen try to be made detectives; and so we find that the foundations of the detective force are laid in the desire for opportunities of manufacturing “cases,” and that the rank-and-file of the force consist of policemen tired of the inglorious business of merely preventing crime.

HOW THE SYSTEM WORKS

Now, how does this system work?

It is plain on the face of it that the only chance the detective has of doing any good is by happening to observe the commission of a crime which would not have been committed at all had a policeman in uniform been in the neighbourhood.

In other words, the detective detects crime which the presence of the policeman would have prevented – a very doubtful gain.

We certainly do occasionally hear of a pickpocket being betrayed by the unsuspected eye of an officer of the law.

But in the case of a crime committed in such a way that the criminal escapes for the moment, what happens?

Of such crimes there are two classes – one in which the offender is known and has merely to be hunted down, the other in which the offender is not known.

FINDING A CRIMINAL

To find a runaway who has committed a theft, a forgery, an embezzlement, or a murder, is a comparatively simple matter.

The telegraph speedily encloses him in a circle of close observation from which he can hardly escape.

But it is different with a crime of which the author is not known – of a burglary, or a murder, the perpetrator of which has to be sought for among the thirty-odd millions of people who inhabit these islands.

How does our detective system work in such a case?

Information of the crime is circulated; descriptions are given of the missing property or the murdered victim; all the pawnbrokers, lodging-house keepers, and other persons under the supervision of the police are communicated with: and there the effort ends.

If the offender has plenty of money, the chances are a thousand to one that he will get clear away.

If not, he will be starved into betraying or surrendering himself long before the detectives will have got upon his track.

THE PLAIN CLOTHES POLICE ARE USELESS

The plain-clothes constables are of no use whatever; for they are only policemen, and if they had not been policemen would probably have been soldiers, sailors, or labourers.

Their superior officers are but little better; for they are only a higher grade of policeman, to whose minds their promotion has merely brought an added sense of their own importance and a suspiciousness which betrays itself at every turn.

In the whole body of them there is no resource, no initiative, no capacity for putting two and two together – none of that imagination which quickens a few facts into a sound generalisation, or of that instinct which supplies the missing links in a broken chain of evidence.

GROPING IN THE DARK

From the first the operations of the detective force are a mere groping in the dark; and even in this its members are handicapped by their outward and visible brotherhood with the men of buttons and baton.

It is time that these facts were recognised at Whitehall.

The sum of them all is, that we have a uniformed police force and a plain-clothes police force, but no detective force.

It may be desirable to keep the present organisation: but it should at once be supplemented by another – by an organisation capable of tracking unseen the footsteps of the criminal, and of building up from facts theories which in turn are to become facts themselves.

Not in numbers, but in character, organisation, and method is the improvement needed.

No one expects a detective to do impossibilities; but while the present force does perhaps as much as can be expected from it – and in some instances a good deal more – no one can pretend that it fulfils all the functions of which a proper system would be capable.”