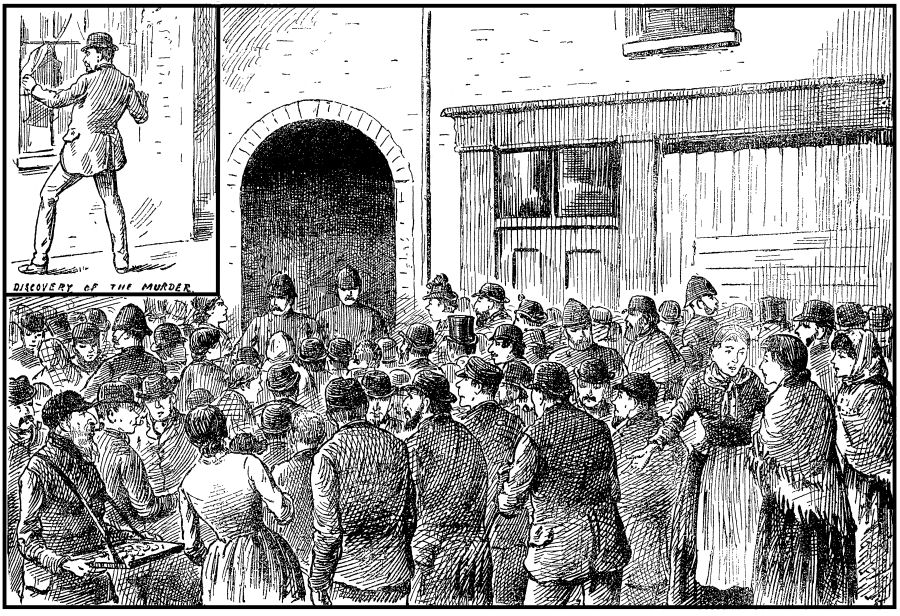

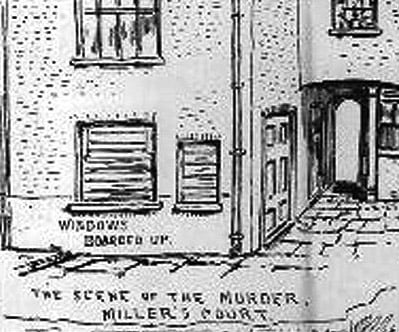

Mary Kelly, whom many believe to have been the final one of Jack the Ripper’s victims, was murdered in Miller’s Court on the 9th November 1888. However, her’s was not the only murder to have taken place in this rather ordinary and, somewhat down-at-heel little court, situated off Dorset Street in Spitalfields in the East End of London.

MURDER CENTRAL E1

Indeed, between the murder of Mary Kelly in 1888 and the demolition of Miller’s Court, several other murders took place in this tiny enclave – so much so that Miller’s Court could be easily classed as Murder Central in the East End of London.

FOUR RESIDENTS IN ONE ROOM

Elizabeth Roberts shared a room in Miller’s Court with her husband, David – who was a painter and decorator by trade – her three year old son, and her sister Kate Marshall.

Elizabeth and Kate both worked as whip-makers, a trade they carried on in the tiny room in Miller’s Court.

26TH NOVEMBER 1898

At 7.30am, on the 26th November 1898, David Marshall went out to work leaving his wife, son and sister-in-law in the room. He returned home at around 6.30 pm to find that Kate had gone out and only his wife and son were in the room. He later recalled that his wife was “quite sober at the time.”

A NIGHT AT THE BRITTANNIA

At 7.15 pm, Elizabeth left to join her sister Kate at the Britannia Public House at the Junction of Dorset Street and Commercial Street and the two spent the night drinking, leaving at 11. 45 pm. The two of them arrived back at the room at around midnight and were carrying a quart can of beer, from which Elizabeth poured her husband a glass which he drank whilst in bed.

KATE AND ELIZABETH ARGUE

The two women then started arguing over the profits from their work. Suddenly, the quarrel turned violent with Kate rushing at Elizabeth and the two of them falling against the table, overturning it before both fell onto the bed and then to the floor. Leaping up, David wrestled the two women apart and then returned to the bed to comfort his son who had become distressed by the incident.

KATE STABS ELIZABETH

The two women continued their quarrel and, suddenly, Kate lunged at Elizabeth screaming “You thing, I will give you something for this.” Mr. Roberts saw Kate strike Elizabeth on the breast, whereupon his wife turned and told him “Dave, she has stabbed me.”

Setting the child down, David Roberts seized his sister-in-law by the wrists and managed to wrestle her out of the room and onto the landing where he called for help.

THE NEIGHBOURS ARRIVE

His cries brought Charles Amory, his neighbour, out onto the landing, who later described the sight that greeted him as he opened his door:-

“I opened my door, and saw Roberts struggling with the prisoner – they were standing up struggling when I first saw them, and then Roberts got the prisoner, on the floor, holding her two wrists—I saw the deceased coming along the landing towards her husband with a terrible gash on the right breast – Roberts gave me the knife, which he snatched out of the prisoner’s hand – I saw him take it from her hand – he said, “Take this knife” – there was blood on the blade and the handle stuck to my fingers – when the knife was given to me the deceased fell on the top of the stairs.”

Mary Johnson, who shared the room with Amory, also came out and witnessed Roberts struggling to pin Kate Marshall down. She saw Elizbeth Roberts clutching her hands to her head and looking very distressed and she promptly ran to fetch a policeman.

PC FRY ARRIVES

By the time she returned with Police Constable Fry, Elizabeth Roberts was slumped unconscious on the landing and was, according to Fry’s later testimony, in a sitting position with her feet towards the staircase. She had “a large wound over the right breast, and a long cut on the left arm.” Fry immediately blew his whistle to summon assistance.

David Roberts, meanwhile, was still struggling with Elizabeth Marhsall who was, so Fry later recalled, “acting like a mad woman…very excited.”

In her frenzy, she had managed to rip David Roberts’s shirt almost completely off and, as the constable arrived, Roberts cried to him “this woman is my wife, and this woman has stabbed her; take hold of her while I get my clothes on.”

THE DOCTOR IS SENT FOR

A fellow constable was soon at the scene and Fry sent to fetch a doctor. Police Constable Randall had also answered Fry’s whistle and he then took hold of Marshall and manhandled her down the stairs at which point, according to Annie Jackson – who lived in the same room as Charles Amory and Mary Johnson – Kate Marshall’s demeamor changed and she cried out in remorse:-“Oh my God, what have I done? Let me go back and kiss her; I must have a kiss if I die for it.”

With the situation under control, Constable Fry attempted to render what assistance he could to the victim and awaited the arrival of the doctor.

DOCTOR HUME TRIES TO SAVE HER

Dr David Hume of White Lion Street was at the scene by 12.20 am and found the stricken woman sitting on the landing, but unconscious. According to his later testimony she was:-

“…suffering from a wound in the right breast – she was taken into Amory’s room – I tried to revive her with brandy, but she died a few minutes later.

She also had a wound on her left arm; it was about two inches long; it was a cut not a stab.

On November 28th I made a post-mortem examination—there was an incised wound in the right breast, and puncturing the lung for about one inch—it had gone through the cavity of the chest – it was the cause of death…I went to the police-station, and saw the prisoner there about 1.40—she was under the influence of drink – I saw Roberts when I was attending to the deceased; he was perfectly sober…”

KATE MARSHALL CHARGED WITH THE MURDER

Kate Marshall, meanwhile, had been taken to nearby Commercial Street Police Station, where she was met by Inspector William Evans who informed her that “The woman who it is alleged you have stabbed is now dead, and I caution you against any statement which you may make, as I shall use it in evidence against you.” He later recalled that her tearful response was:- “That woman is my sister; my God, if it had been any other person than my sister I would have cared. Oh my sister! O Liz, O Liz!”

At 4.30 am that morning Kate Marshall was charged with the “wilful murder of Elizabeth Roberts,” to which she replied “I hear, I am innocent.”

KATE MARSHALL’S OLD BAILEY TRIAL

Her trial began before Mr Justice Darling at the Old Bailey on the 9th January 1899. Giving evidence on her own behalf, she denied stabbing her sister, and claimed that the murder had, in fact, being carried out by the deceased’s husband, David Roberts.

However, when, under cross-examination, she was forced to admit that she had had several previous convictions for stabbing people her claims of innocence fell apart and the jury found her guilty – albeit they strongly recommended mercy on the grounds of “the absence of premeditation, and being done in a state of drunken frenzy.”

SENTENCED TO DEATH

Mr Justice Darling, though, was in no mood for leniency and he sentenced her to death, although the Home Office later commuted the sentence to one of life in prison.

A BIZARRE POSTSCRIPT – THE KNIFE REQUESTED

There is an intriguing, even bizarre, after tale to this case in that, on the 20th January 1899, at Bow Street Police Court a solicitor by the name of Mr Holloway, acting on behalf of her solicitor, Mr Havelock, applied for a summons, requiring the Metropolitan Police Commissioner to show cause why he should not ” deliver to Mr. Havelock…the knife with which the murder was committed.”

According to Holloway, the “knife had been assigned by the condemned woman to Mr. Havelock [and] It was not disputed that this knife was her property.

Sir John Bridge, presided, was disdainful of the request and stated that, even if he granted a summons, he should certainly not make an order for the delivery of the knife.

Mr. Holloway argued that lawyers who had been consulted had advised that this assignment constituted a valid claim for the knife.

WANTED FOR A MONSTROUS PURPOSE

Mysteriously, Bridge concluded that he was in no doubt that “this solicitor wanted the knife for a certain purpose, and he considered this perfectly monstrous [and] in the circumstances he thought it would be wrong to give up the knife, and he should not grant a summons.”

One is left wondering what the “monstrous purpose” could have been? The only possible conclusion to draw is that he wanted it for to sell, or keep, as a souvenir!