Emily Coombes was worried.

Her sister-in-law, also named Emily Coombes, had not been seen since July the 6th 1895.

The two women had known each other for many years. Not only did they share a common Christian name, they had also married two brothers and, as a consequence, both of them had the surname of Coombes in common, so both of them were named Emily Coombes.

AN EXEMPLARY WIFE AND DEVOTED MOTHER

Her sister-in-law had married Robert Coombes, who worked as a purser and chief steward for the National Steamship Company, and the two had moved into a neat, little, yellow-brick house at 35 Cave Road, Plaistow, where they were raising their two sons, Robert (aged 13) and Nathaniel (aged 10).

A MUCH RESPECTED FAMILY

The parents were, according to later newspaper reports, “much respected in the neighbourhood.” Indeed, neighbours described Robert and Emily Coombes as very pleasant, cheerful people, and Mrs Coombes was, by all accounts, an exemplary wife and mother, and a careful housewife.

The neighbours, however, do not appear to have been similarly enamoured of the two boys, who they described as being “sullen and morose, and resembling neither of their parents.”

Furthermore, they “were known to have been deceitful and dishonest in small things,” and local opinion was that their mother was “very fond of them” and that she “regarded their faults too leniently.”

On Friday 5th July 1895, Robert Coombes bade his 37-year-old wife and their children “goodbye” and headed for the nearby docks from whence he set sail for New York aboard the steamship France.

He had, however, left his wife with sufficient money for all her household needs during his time away.

WHERE IS YOUR MOTHER?

By the Monday following Robert Coombes’s departure, several of the Cave Road neighbours became concerned that they had seen nothing of Mrs. Emily Coombes for several days and had begun enquiring after her with her two sons. However, the boys response was always that their mother had “… gone to Liverpool to see father,” and, since the story seemed believable, it was accepted in the neighbourhood as true.

A DISAGREEABLE ODOUR

But then, on Tuesday July 8th, 1895, neighbours began to notice a disagreeable smell emanating from the property at 35 Cave Road. Believing that the boys were neglecting the sanitation at the house, they quizzed them about the stench, but were assured that everything was alright.

Evidently, the residents of Cave Road, saw nothing wrong with two boys being left alone at home!

THE CHILDREN’S AUNT, EMILY, SENT FOR

One neighbour, however, was growing suspicious that things were not as rosy as the two boys were claiming, and she, therefore, sent word to their aunt, Emily Coombes, informing her that she did not think that all was well inside 35 Cave Road.

Emily had gone round to the house in Cave Road on several occasions, but no-one had answered her repeated knocking at the door.

This she found extremely worrying, although evidently not worrying enough to notify the police that something was amiss!

THE STRANGE MAN AT THE DOOR

On Monday 15th July 1895 she returned to the house at 6pm.

The door this time was answered by a man whom she had never seen before, but whom she would later learn was named John Fox, who was 39 years old.

SHE’S GONE TO LIVERPOOL

The man only opened the door very slightly and looked at her around the narrow opening.

“Can I see Mrs. Coombes?” she asked.

His reply was a curt “No, she is not at home.”

“Where has she gone?”, Emily asked.

“On holiday”, was the reply.

Insisting that she was Mrs. Coombes sister-in-law and that she wanted to know where she had gone, Emily tried to insert her foot into the door, but she was unable to do so.

Informing her that Mrs Coombes had gone “to Liverpool”, the man promptly shut the door.

Again, Mrs Coombes appears to have been unconcerned that a strange man, whom she had never seen before, was answering the door of her sister-in-laws house and was, apparently, there alone with her two nephews.

ROBERT LIES TO HIS AUNT

Perhaps her fears were allayed by the fact that, at this point, her nephews, Robert and Nathaniel, came walking up the street and approached the door?

“Where is you Ma?”, she asked the elder of the two, Robert.

Confirming what the youth had told her, Robert replied that she had “gone to Liverpool.”

A rich aunt, he explained, had died and had “left them a lot of money.” He knew nothing about this aunt, he said, “all he knew was that she was very rich.”

At this point the two boys joined a group of other boys and headed off in the direction of the recreation ground, whereupon Mrs Coombes left the scene.

EMILY RETURNS TO THE HOUSE

However, the fact that she hadn’t been able to gain access to the house played on Mrs Coombes’s mind and, two days later, on Wednesday 17th July 1895, she returned to the house at around 9 o’clock in the morning.

She knocked two or three times, but received no answer.

Returning at midday, she knocked again.

This time the door was opened, but in her later testimony she couldn’t remember who by, other than stating that “it was a man I think, I could not be sure.”

SHE FORCES HER WAY IN

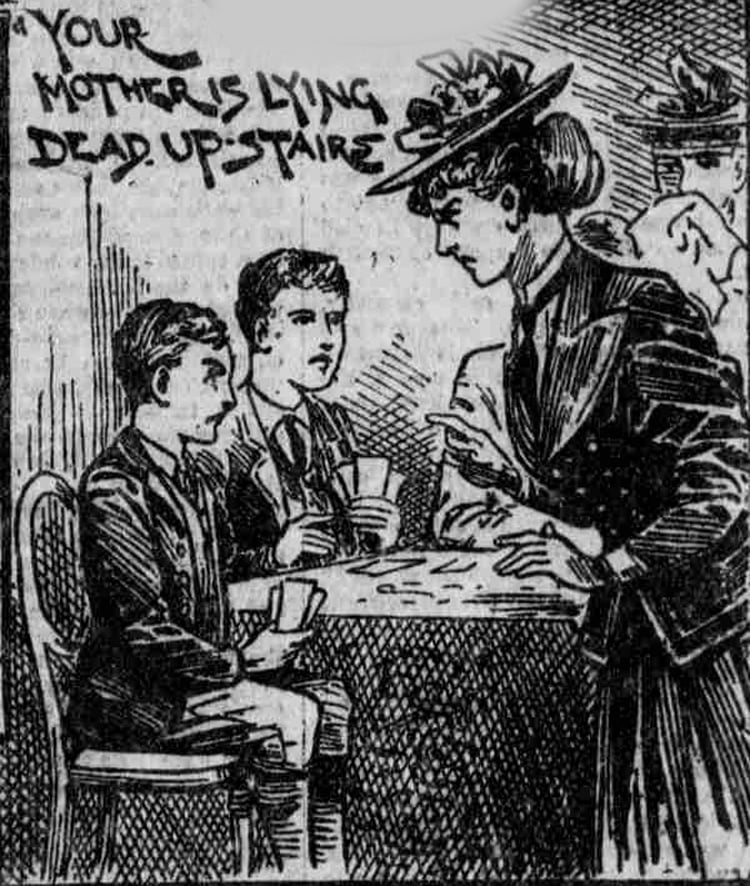

Mrs Coombes had more pressing matters on her mind, other than taking notice of who answered, and the moment the door was opened, she forced her way in and went straight to the back parlour, where she found her two nephews and the man who had answered the door two days previously playing cards.

They promptly scrambled to their feet. “Where is your Ma?” She asked Robert. He told her that she was round at Mrs Cooper’s and offered to take his aunt round to see her. But, Mrs Coombes was not about to be fobbed off and told him that she knew that “his Ma was in this house, and I would not go out until the police came.”

By this point, the younger brother, Nathaniel. had scrambled out through the window and was in the garden.

Mrs Coombes asked Robert if she could “go into his Ma’s bedroom”

She later stated that his reply was “no I could not, it was locked – I asked where the key was; he said he did not know – I then went up to the front bedroom to burst the door open – I found it was locked.”

THE GRUESOME DISCOVERY IN THE BEDROOM

Mrs Coombes was not about to be deterred by a locked bedroom door and, in her subsequent testimony, she recalled, in great detail, the events as they then unfolded:-

“Ultimately I borrowed a key from the landlady, unlocked the door and went in, and there saw the dead body of my sister-in-law on the bed.

I sent for a constable, and Constable Thwart(some newspaper accounts give his name as Ewart) came – I then came downstairs again into the back parlour.

A BAD, WICKED BOY

The two prisoners were still there – I said Robert was a bad, wicked boy, he knew his mother was dead, and he ought to have come and told me.

I’LL TELL YOU ALL ABOUT IT

He said, “Auntie, come to me and I will tell you the truth, and tell you all about it.”

He told me his Ma had given Nattie a hiding on the Saturday, and she would give him one, and Nattie said he would kill her; but he said, “I cannot do it Bob, will you,” and I did it.

He said, “I slept with mother on Sunday night, and I kicked about, and mother pushed me, and I got out of bed and killed her; Nattie was in the back room, and coughed twice, that was when I done it, when Nattie coughed.”

I said, “Did your mother cry – he said, “No” – I asked whether she was awake when he did it – he said, “Yes, with her hand over her face” – I asked him what time it was – I think he said, “about a quarter to four on the Monday morning, a week ago”, she had been dead ten days – I asked him what he did then – he sad he covered her over and went to Lord’s Cricket Ground. I said, “Where is your father’s gold watch” – he said, “I have pawned it, I gave it to John Fox to pawn, and some other things” – he was going to give me the ticket but the police came up, and he handed it to the sergeant – I told Fox he was a bad man – he said he did not know anything about it; that was all he said to me – I noticed that Fox had got on my brother-in-law’s clothes, a new suit – when I went to the house on the 17th before going upstairs I noticed a nasty smell of strong tobacco, that was all – Fox was smoking when I went in.”

POLICE CONSTABLE THWART ARRIVES

Soon Police Constable Robert Thwart had arrived on the scene, and he headed upstairs:-

“I saw on the bed the form of a woman with a pillow over the face – I removed the pillow, and saw the face – it was very much disfigured; the smell in the room was awful – I saw this dagger-knife on the foot of the bed – this bludgeon was on the floor; it is a truncheon; it was lying between the bed and the window – I sent for Doctor Kennedy – I went downstairs into the back parlour, and there saw the prisoners Robert Coombes and Fox”

ROBERT CONFESSES TO THE POLICE

He proceeded to caution Robert that anything he said would be used in evidence against him. Robert informed him that:-

“I did it. My younger brother, Nattie, got a hiding for stealing some food, and Ma was going to give me one, so Nattie said that he would stab her, and as he could not do it himself he asked me to do it, and said, “When I cough twice you do it,” which I did, and I am sorry that I did it. I did it with a knife, and left it on the bed, covered her up, and left her. ”

WHAT THE POLICE SURGEON SAW

As he was interviewing the boy, the Divisional Police Surgeon, Alfred Kennedy, arrived. He later testified as to the sight that greeted him in terms that are both graphic and harrowing, despite the passage of 121 years:-

“I found in the front bedroom upstairs, lying upon the bed and on the left-hand side of it, the body of deceased – she was lying on her back, slightly inclined to the left side – the body was in a horrible state of decomposition; the nose, eyes and ears had been entirely eaten by maggots – on exposing the chest, I found on the left side, over the region of the heart, two gaping wounds – the chemise, bedclothes, and bedding were stained with dried blood – this knife would be a weapon likely to produce the wounds I saw – it was shown to me afterwards by the police; there was blood on it when I examined it, and there are dried blood stains on it now – the smell in the room was frightful – before I got into the house I noticed the smell; the front door was open when I arrived – the buttocks and calves of the legs and other parts of the body were also destroyed by maggots…”

MURDER OF A MOTHER AT PLAISTOW

As news of the murder began to spread throughout the neighbourhood, the newspapers started sending journalists to Cave Road to see what information they could glean from the neighbours about the family and the scene of the crime.

According to an article in Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, which appeared on Sunday 21st July 1895, it had come as “a great shock to everyone when it was announced on Tuesday that Mrs. Coombes had been murdered and had lain dead in her room since the previous Monday week, the 8th inst.”

It came as an even greater shock that the perpetrator of the crime had, in fact, been her own son, Robert.

Furthermore, the neighbours were struggling to comprehend the revelation that “her two sons had been in and out of the house as usual, and the younger one had regularly attended school,” during the week or so in which the body of their dead mother lay decomposing in her upstairs bedroom.

Indeed, “the conduct of the boys excited no suspicion. Both boys partook of their meals in the house, and slept there, in the back bedroom, every night. They seemed to think nothing about their mother lying dead in the house.”

VERY STRANGE INDEED

The whole thing was beyond the comprehension of the residents of Cave Road and the behaviour of the two boys was, to say the least, very strange indeed.

The matter-of-fact-way in which Robert had described the cold and callous manner in which he had murdered his mother was particularity chilling.

But then, as we shall see in part two of the article, Robert Allen Coombes was anything but your average thirteen year old boy.

And, as for their dead mother.

Well, it would appear that their neighbours description of her as an exemplary mother and pleasant person may well have been due to a reluctance to speak ill of the dead.