In the last instalment of our blog on the murder, in July 1895, of Emily Coombes in Plaistow East London we revealed how her 13-year-old son, Robert, was charged with the crime.

If you missed the previous instalment, you can catch up with it here.

In the aftermath of the murder, neighbours told journalists that Emily had been an exemplary wife and mother. But, at her son’s subsequent Old Bailey Trial, a somewhat different image of her emerged.

AN EXCITABLE WOMAN

Next door neighbour, Mrs Ingrams, for example, told how she had known the family for three years and that she had found the mother to be “rather excitable all the time I had known her.”

The family doctor, John Joseph Griffin, testified that:-

“I attended the Coombes family for the last two years – the mother was of a hysterical disposition, very emotional, and subject at times to fits of crying and laughing, and to attacks of hysteria – she used to laugh and cry with the least exciting cause – she was generally of a weak and nervous disposition…”

Her widowed husband, Robert Coombes Snr, testified that:-

“I have been married seventeen years – Robert was my first child – I had been married four or five years before he was born – my wife was a very excitable woman from the first, very frequently laughed and cried at the same time – I was not at home at the time of Robert’s birth, I think I had just gone to sea, or came home just afterwards, I cannot recollect – I know that my wife had a very bad time.”

Mr Coombes, however, also stated, on oath, that:- “There is no insanity on my side of the family or my wife’s either.”

ROBERT COOMBES’S MENTAL STATE

Robert’s mental health was subjected to a great deal of discussion over the course of his trial at the Old Bailey, which began on the 9th September 1895.

In the aftermath of the murder, neighbours had stated that he was a “sullen and morose” boy, and that he was “known to have been deceitful and dishonest in small things.”

However, at his trial it emerged that 13-year-old Robert Coombes was an extremely troubled teenager.

According to his father he had been troubled for all of his life, and the fact that his birth was a difficult one may well have resulted in the mental illness that plagued his childhood. Testifying at the trial, Robert Coombes Snr stated that:-

“I first noted signs of excitability about him when he was about three or four years of Age – he always complained of headaches – in disposition he was a very good boy – I took him to Dr. Coward when he was three or four to see what was the matter with him – he always complained of those bad headaches…”

He also mentioned the fact that his son had birthmarks on his temples, which were caused by instruments that had been used during his delivery at birth.

DR GRIFFIN COMMENTS ON HIS MENTAL STATE

Dr John Joseph Griffin, the family’s physician, made specific reference to the birthmarks during his testimony:-

“…the lad was brought to me by his father, and sometimes by his mother – the last time was December 1894 – he was suffering from attacks of mental excitement due to cerebral irritation – his father brought me two papers, in consequence of which I prescribed for a disordered nervous system – when the attacks were on him he had an irresistible impulse to run away without reason – I advised his father to take him to sea for a trip in consequence of these attacks – what I saw might develop into mania – and from what I have heard since, the boy has changed for the worse from what I saw last, physically and mentally – the disorder is of a progressive nature, and has got worse in my opinion – I form the opinion from what I have seen of him and what I saw yesterday – I have noticed the birthmarks on his temples…they show very considerable pressure and violence had been used…”

WAS VIOLENT LITERATURE TO BLAME?

When Police Inspector George Gilbert gave evidence, he spoke of having conducted a search of the house at 35 Cave Road, where the murder had occurred.

The search, he said, took place on the evening of the 17th and the morning of the 18th July 1895.

One revelation from his testimony led to a great deal of speculation as to what may have influenced Robert Coombes to commit such an horrendous crime. The inspector revealed that he had come across “books in the back parlour; they are apparently sensational stories.”

Asked about these books, Robert Coombes Snr, replied:- “he is a very learned boy, he read a great deal – he has not to my knowledge been reading sensational books – the books that were found in the house were good books, such as the Strand Magazine and the New York Century – he took an interest in the trial of criminals…”

However, and despite what his father said, it transpired that the books in question were, most certainly, sensationalist.

Mr Grantham, for the defence, tried to forge a link between his client’s enjoyment of “sensational stories” and a motive for the crime by claiming that, given the boy’s mental state, this type of “pernicious literature would be very bad for such a boy to read.”

At this point the judge spoke up and opined that “It would have a bad effect upon the mind of any boy, I should think,” to which Mr Grantham replied, that it would be worse for a boy “suffering from mental affections…”

This revelation led to speculation in several newspapers that Robert Coombes Jnr’s interest in the “Penny Dreadfuls” may have, in some way, influenced the act of matricide. Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, for example, in its edition on the 22nd September 1895, commented that, “Like most young criminals he was a reader of the worst fiction.”

The Illustrated Police News was a little more fulsome in its condemnation of the type of literature that Robert seemed to enjoy, despite the fact that, when it came to sensationalism, its own track record was far from blameless, so much so that it had once been dubbed England’s Worst Newspaper!

Commenting on the case it informed its readers that:-

“Both Robert and Nathaniel have been greedy devourers of sensational literature; indeed, there have been found in the house all kinds of penny ‘dreadfuls’ and blood-curdling narratives … The demoralizing influence of pernicious reading had begun to tell on the boys for some months, particularly on the elder, who a few years ago was treated by a now deceased doctor at Bow for a brain affection.”

Even the jury at the inquest into the death of Emily Coombes had raised the issue by adding a condemnation of the type of literature that they felt may have disturbed Robert’s already disturbed mind further to their verdict of “Wilful murder:-

“…the Legislature should take some steps to put a stop to the inflammable and shocking literature that is sold, which we are of the opinion leads to many a dreadful crime being carried out”

In other words, the argument as to whether or not depictions of crime and violence in the media could be blamed for crimes of violence in reality was being raised – and it’s an argument that still rages today!

CHILLING REVELATIONS

Also called to give evidence at the trial of Robert Coombes was his younger brother, Nathaniel Coombes.

During an earlier appearance, at West Ham Police Court, there had been “very careful consideration” of Nathaniel’s “position in the case,” and the decision had been taken to discharge him. He would, however, it was decided, be put in the witness box and would be “asked to tell the story as he knew it.”

NATHANIEL TELLS WHAT HAPPENED

Testifying at his brother’s Old Bailey trial, Nathaniel had this to say:-

“Robert and I slept together in the same room, the back room upstairs – on the Saturday night I think Robert slept with my mother, and on the Sunday I slept in the hack room by myself – between half-past eight and nine on the Monday morning Robert came into my room, and told me he had killed my mother – I said, “You have not” – he said, “Come in and look” – I went into mother’s room; I heard her groaning like – I did not see her exactly; I don’t think I went in half a yard from the door; I looked at the bed, but I could not see her – I went back to my room – I don’t know what my brother did – he did not come back to my room – I went to bed again – on the Friday or Saturday before, he said to me he would try and do it – he had spoken about it once before that, I could not tell how long before – it was not in the same week -the first time he spoke about it he said he was going to kill my mother – he said he wanted to get away to some island – he said he was going to stab her – he bought a knife – I was not with him when he bought it – he showed it to me – I think that was about three days before the Monday – this (produced) is the knife – he said, “That is the knife I am going to do her with,” that was after my father had left home – my mother has beaten me several times – she hit me on the Sunday before she died – I was naughty. Robert was present when she beat me he said, “If you cough twice that will show that I will do it” – he said that on the Saturday, I think – I did not cough – on the Monday evening he brought mother’s dress into my room and got the money, out of the pocket – it was in a purse I could not tell exactly how much there was – it was some in gold and some in silver…”

He then went on to state how they had been on several excursions – including to Lord’s Cricket Ground – and how, on the Wednesday following their mother’s murder, they had gone to fetch John Fox, the man who had initially answered the door when their aunt, Emily, had come looking for their mother.

Significantly, he stated that Fox did not go into their mother’s room and that they had, all three of them, slept in the downstairs parlour.

As a result of Nathaniel’s testimony, John Fox was later found not guilty of any involvement in the crime.

CONDITIONS INSIDE THE HOUSE

Something of the horrific conditions inside the house at 35 Cave Road can be gleaned from his revelation that:-

“The door of my mother’s room was opened about twice after the Monday; I think it was opened on the Thursday, and I think on the Monday following; my brother opened it; I saw him go in; I could not say whether he went into the room or not, I saw him open the door, he went to see if she was all right…when my brother opened the door during the week there was a smell – I was going upstairs on the Thursday, when the door was opened – I noticed the smell as soon as the door was opened – I did not notice it after the Thursday – on the Monday when the door was opened the smell was the same…”

NATHANIEL REMEMBERS HIS MOTHER, EMILY

Remembering their mother and the immediate aftermath of her murder, Nathaniel stated that:-

“Mother was very kind, and did all she could for us both – my brother ran away from home suddenly on two occasions, I think – he took me with him – he asked me to go with him – our father said nothing about it – Robert has often complained of pains in the head, headaches, and has been excitable – I never coughed on the Sunday night; I was sound asleep all night till he called me, between four and five – there is no clock in my room; he brought the clock into my room to show what the time was – he was quite calm, and knew what he was saying then – we went out about 5.45 that morning, I think – after he came into my room he got up; he said nothing to me about going back to sleep.”

One statement made by Nathaniel during his evidence caused genuine revulsion in court, and several newspapers commented on how there were loud groans at the revelation. He had, he said, asked his brother what he intended to do with their mother’s body. His reply had been that he was going to cover her in quicklime.

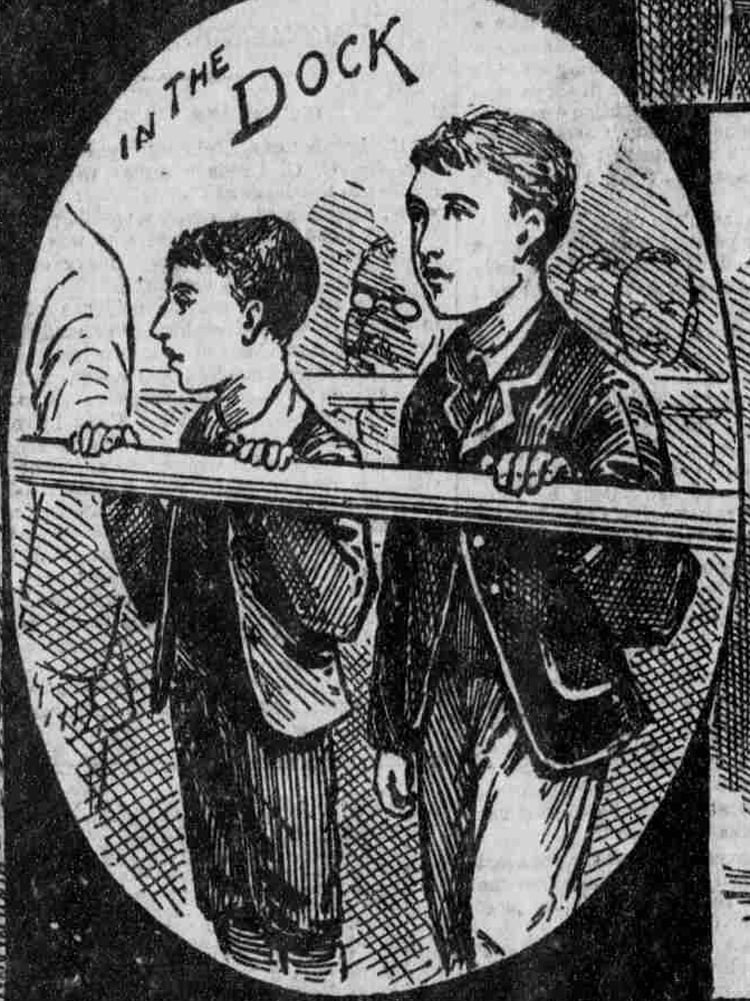

With Nathaniel’s testimony over, the court began turning its attention to the mental state of Robert at the time of the crime. Was he mad or bad?

HE GRINNED AND GRIMACED

Robert’s behaviour during his trial, elicited comment in the newspapers as they tried to contrast his youthfulness with the sheer horridness of the crime he had committed.

Several newspapers commented on the fact that his behaviour during the trial was far from normal.

He would, for example, grin when evidence was being given. He would sometimes bury his head in his hands, and on several occasions he, according to the Daily News on Wednesday September 18th 1895, “made hideous grimaces at the judge and witnesses.”

Whilst in Holloway Prison, awaiting trial, he had had to be placed in a padded cell and, so the Daily News informed its readers, “had sung and whistled and was impudent to the officials.”

GEORGE EDWARD WALKER’S TESTIMONY

However, the most revealing testimony regarding the mental health of Robert Coombes came from George Edward Walker, the Medical-Officer of Holloway Prison and Newgate Prisons, who had been looking after the boy since the 18th July 1895 and who had, therefore, “watched him carefully” for the previous few months.

He told the court that Coombes had seemed to him a very clever boy and that “as a rule he was well behaved.” However, he had noticed a change in his behaviour around the 5th of August when his “…excitability was especially noticed and [he] would not do what he was told – he was singing and whistling, and was very impertinent to the officers…”

The doctor then went on to say hwo:-

“…he has complained of pains in the head on two or three occasions – he told me he had suffered from them more or less all his life – there is a distinct scar on his right temple, and on very careful examination I noticed also a very faint scar just in front of his left ear – those scars might have been caused by instruments used at the time of his birth – the brain is always compressed more or less when instruments are used, which will occasionally affect the brain – I believe children have suffered from fits afterwards – I have come across such cases, and I think it has been stated to me by the mothers – generally the marks disappear, but in this case there is a distinct mark of a wound – it depends upon whether the flesh has been injured or not – in this case considerable violence must have been used – and from the violence there must have been considerable pressure on the brain – I have noticed that his pupils are at times unequal – the variability of the pupils shows that the mischief is not in the eye, but is probably due to cerebral irritation – I asked him whether he heard voices – he said at night he had heard voices saying, “Kill her, kill her, and run away” …I questioned him closely as to those voices, how they seemed to speak to him, and he stated that they seemed to whisper into his ear – he said he killed his mother because he was afraid that if he did not do so she would kill his brother Nathaniel, and that she had often threatened to knock his brains out with a hatchet, and had thrown knives at him – he said he had an irresistible impulse to kill her…”

GLEEFUL ABOUT GOING TO TRIAL

Mr Walker also testified that, around the 10th of September 1895, he noticed that the boy was “suffering from cerebral excitement” and commented that:-

“…it was peculiar – he appeared in very great glee at being about to be brought here to be tried – his manner was peculiar…he thought it would be a splendid sight, and he was looking forward to it – he said he would wear his best clothes and have his boots well polished – then he began to talk about his cats – from having been very talkative he suddenly became very silent and burst into tears – I asked him why he was crying, and he said because he wanted his cats and his mandolin.”

A LETTER FROM AN INSANE PERSON

Walker also showed the court a letter, written by Robert Coombes, which, he said, had been handed to him on Sunday and which, he opined “appears to be written by an insane person.”

The letter was addressed to The Reverend Mr Shaw, 538, Barking Road, Essex, and it is worth quoting it in full:-

” From R. A. Coombes, H.M.S. Prison, Holloway, 14.9.’95

“Dear Mr. Shaw,

I received your letter on last Tuesday. I think I will get hung, but I do not care as long as I get a good breakfast before they hang me.

If they do not hang me I think I will commit suicide. That will do just as well. I will strangle myself.

I hope you are all well.

I go up on Monday to the Old Bailey to be tried. I hope you will be there. I think they will sentence me to die. If they do I will call all the witnesses liars.

I remain,

yours affectionately,

R. A. Coombes”

The postscript to the missive consisted of a crude drawing of a gibbet and two figures being pushed forward by a third; over this last figure was written “Executioner.” The drawing was headed,” Scene I, going to the Scaffold.”

A second drawing showed a depiction of a gibbet with a person being hanged, and the words “Goodbye” issuing from the mouth, followed by the statement – “Here goes nothing!”

Finally the boy had written:- “My will: To Dr. Walker, £3,000; to Mr. Payne, £2,000; to Mr.Shaw, £5,000; to my father, £60,000; to all the warders, £300 a piece. Signed, R. Coombes, Chairman, solicitor. P.S. Excuse the crooked scaffold, I was too heavy, I bent it; I leave you £5,000.”

GUILTY, BUT INSANE

With al the witnesses having given their evidence, the Jury retired to consider their verdict.

After an hour they returned and the foreman stated that “they found Coombes guilty; but they strongly recommended him to mercy on the grounds of his youth, and they thought he did not realize the serious nature of the act.”

The Judge, Mr Justice Kennedy, told them that they must find “distinctly whether the prisoner was or was not insane” and instructed them to retire again and consider their verdict.

Returning, they said that they “found him guilty, but that he was insane when he committed the act.”

ROBERT BECOMES EXCITABLE

At this point, Robert Coombes became very excitable and, as several newspapers noted, he smiled as he turned rapidly to the warden standing nearest to him and whispered something to him.

Mr Justice Kennedy then informed him that “…the only judgement I can give is that the prisoner, Robert Allen Coombes, be detained in strict custody in the gaol at Holloway until the pleasure of her Majesty be known.

With that, the boy was led from the dock. As he was so, according to the St James Gazette, on the 18th September 1895:- “…he laughed audibly, and observed to the warder, “It’s all over now.”

SENT TO BROADMOOR

Ultimately, he was sent to Broadmoor, where he became the youngest patient. He remained there for 17 years and was released in 1912, at the age of 30.

GOES TO AUSTRALIA

Upon his release, he emigrated to Australia and went on to serve with great distinction as a stretcher bearer in the army during the First World War.

THE WICKED BOY

His story has recently become the subject of the latest book by Kate Summerscale – the author of The Suspicions of Mr Whicher. You can get full details of the book, and purchase a copy, from any good book store, or by clicking here to go to Amazon.