The murder of Mary Nichols, who many now believe to have been the first victim of the killer we now know as “Jack the Ripper”, took place in Buck’s Row – now called Durward Street – in the early hours of Friday, August the 31st, 1888.

Today, we know that the body was discovered by Charles Cross as he made his way to work along Buck’s Row at around 3.45 that morning.

No sooner had he noticed the body lying in a gateway on the left of the western end of the first section of Buck’s Row, than he was joined at the scene by a second man, Robert Paul, and together they carried out a brief examination of the body, before deciding to continue on their way to their respective places of employment, agreeing that they would tell the first policeman they encountered of their find.

POLICE CONSTABLE NEIL

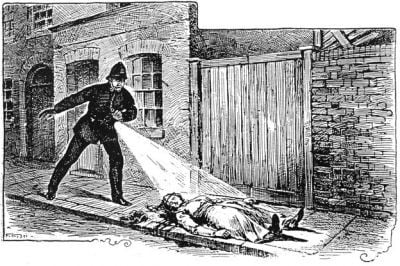

Shortly after they left the scene, Police Constable John Neil, of the Metropolitan Police’s J Division, walked his beat along Buck’s Row, and noticed a woman lying on the right side of the thoroughfare.

Approaching, he shone his lamp onto her, and saw that blood was oozing from an open wound in her throat and had pooled by her neck.

CONSTABLE THAIN

At this point, he noticed Police Constable Thain passing the Brady Street end of Buck’s Row, and signalled to him with his lamp.

Upon Thain’s arrival, Neil sent him to fetch the nearest medic, Dr. Ralph Llewllyn, whose surgery was located at 152 Whitechapel Road.

Police Constable Mizen, who had been alerted by Charles Cross and Robert Paul, then arrived at the scene, and Neil sent him for the police ambulance, which, in reality, was nothing more than a wooden hand cart.

IT WAS THOUGHT HE FOUND THE BODY

Since Neil had played such an important part in the early stages of the investigation, it was initially believed that it was he who had found the body, despite the fact that, by the evening of the 31st of August, several newspapers were reporting that it was, in fact, two men had who had made the discovery.

In consequence, when the inquest into the death of Mary Anne Nichols opened here at the Working Lads Institute on Whitechapel Road, before Coroner Wynne Edwin Baxter, on the afternoon of Saturday the 1st of September – a mere stone’s throw from where the murder had been committed – it was Police Constable Neil who was summoned to give evidence concerning the finding of the body.

Reynolds’s Newspaper published a detailed account of his testimony in its edition of Sunday the 2nd of September 1888:-

THE DISCOVERY OF THE MURDER

John Neil, police-constable, 97J, said:-

“Yesterday morning I was proceeding down Buck’s-row, Whitechapel, going towards Brady-street.

There was not a soul about.

I had been round there half an hour previous, and I saw no one then.

I was on the right-hand side of the street, when I noticed a figure lying in the street.

It was dark at the time, though there was a street lamp shining at the end of the row.

THE SCENE OF THE CRIME

I went across, and found the deceased lying outside a gateway, her head towards the east.

The gateway was closed. It was about nine or ten feet high, and led to some stables.

There were houses from the gateway eastward, and the School Board school occupies the westward.

On the opposite side of the road is Essex Wharf.

THE STATE OF THE BODY

Deceased was lying lengthways along the street, her left land touching the gate.

I examined the body by the aid of my lamp, and noticed blood oozing from a wound in the throat.

She was lying on her back, with her clothes disarranged.

I felt her arm, which was quite warm from the joints upwards.

Her eyes were wide open.

Her bonnet was off and lying at her side, close to the left hand.

AN INITIAL CSI

I heard a constable passing Brady-street, so I called him. I did not whistle.

I said to him, “Run at once for Dr. Llewellyn,” and seeing another constable in Baker’s-row, I sent him for the ambulance.

The doctor arrived in a very short time.

I had, in the meantime, rung the bell at Essex Wharf, and asked if any disturbance had been heard.

The reply I received was “No.”

Sergeant Kirby came after, and he knocked.

THE DISCOVERY AT THE MORTUARY

The doctor looked at the woman, and then said, “Move the woman to the mortuary. She is dead, and I will make a further examination of her.”

We then placed her on the ambulance, and moved her there.

Inspector Spratling came to the mortuary, and while taking a description of the deceased turned up her clothes, and found that she was disembowelled.

This had not been noticed by any of them before.

On the body was found a piece of comb and a bit of looking-glass.

No money was found, but an unmarked white handkerchief was found in her pocket.

CORONER’S QUESTIONS

The Coroner asked:- “Did you notice any blood where she was found:”

“There was a pool of blood just where her neck was lying, “Neil replied. “The blood was then running from the wound in her neck.”

“Did you hear any noise that night?” Quizzed the Coroner.

“No, I heard nothing, “ was the police officer’s response. “The farthest I had been that night was just through the Whitechapel-road and up Baker’s-row. I was never far away from the spot.

“Whitechapel-road is busy in the early morning, I believe. Could anybody have escaped that way?” The Coroner asked.

“Oh, yes, sir.” came the reply. “I saw a number of women in the main road going home. At that time anyone could have got away.

“Someone searched the ground, I believe,” observed Baxter.

“Yes,” Neil answered, “I examined it while the doctor was being sent for.

DID THE MURDER OCCUR ELSEWHERE?

At this stage it was being widely reported that the murder had taken place elsewhere, and that the body was then transported to the location at which it had been discovered.

Thus a juryman asked Neil, “Did you see a trap in the road at all?”

Neil replied, “No.”

“Knowing that the body was warm did it not strike you that it might just have been laid there, and that the woman was killed elsewhere?” the juryman pressed.

“I examined the road, but did not see the mark of wheels,” Neil returned.

THE SLAUGHTERMEN

He then concluded his evidence by telling the court that, “the first to arrive on the scene after I had discovered the body were two men who work at a slaughter-house opposite.

They said they knew nothing of the affair, and that they had not heard any screams. I had previously seen the men at work.

That would be about a quarter-past three, or half an hour before I found the body.”

THE START OF THE AUTUMN OF TERROR

As Constable John Neil left the Coroner’s inquest that day, little did he realise that he had been present at the scene of an atrocity that would be the first of a series of similar murders that, within a few weeks, would have gripped, not only the people of the district, but also people all over the world, and which would become history’s most infamous crime spree.

That would be the knowledge of hindsight.

As Neil stepped out of the Working Lads Institute on that long ago Saturday, and made his way through the crowds along the busy and bustling Whitechapel Road, his mind was no doubt buzzing with the horror of what he had witnessed in the early hours of the previous day.

But, unbeknownst to him, and all those who had heard his testimony, Jack the Ripper’s reign of terror had begun.

BUCK’S ROW TODAY

Today Buck’s Row is called Durward Street, and it has changed almost beyond recognition. The murder site sits uneasily alongside the Durward Street exit from Whitechapel Station, and people pass by it day in and day out, most of them oblivious to the horror that took place there all those years ago.

However, the Board School, which Neil mentioned in his testimony, still looms over the site, a silent witness to that August morning in 1888, when Mary Anne Nichols met her tragic end within the reach of its ominous shadow.