In May, 1888, Samuel Smith, of the National Vigilance Society, stood up in Parliament to complain about the “immense increase of vile literature”, in particular, the works of Émile Zola (1840 – 1902), which, so Smith claimed, were being sold in cheap editions to “young girls in low bookshops”, and were not only corrupting their young and impressionable minds, but also encouraging immorality and prostitution.

Smith conceded that he himself had not actually read any of Zola’s works, but, in a moralistically bombastic address he assumed a grave countenance and informed his fellow Members of Parliament that he had it on good authority that, “nothing more diabolical has been written by the pen of man.”

The target of Samuel Smith’s outrage was the elderly publisher Henry Richard Vizetelly (1820 – 1894) and, in consequence of Samuel Smith’s address in Parliament – in September, 1888, it was announced that Vizetelly was to be prosecuted for “Obscene Libel”, specifically for having published Zola’s La Terre [The Soil].

A DEFENCE OF ZOLA

Henry Vizetelly responded to the news that he was to be prosecuted by firing off a missive to the Treasury in which he defended the works of Zola, and in which he argued that some of the greatest authors in English history were “guilty” of equal, if not worse, obscenities:-

“As the Treasury, after a lapse of four years since the first appearance of the translations of M. Zola’s novels, has taken upon itself the prosecution instituted for the suppression of these books, I beg leave to submit to your notice some hundreds of extracts, chiefly from English classics, and to ask you if, in the event of M. Zola’s novels being pronounced “obscene libels,” publishers will be allowed to continue issuing in their present form the plays of Shakspeare, Beaumont and Fletcher, Massinger, and other old dramatists, and the works of Defoe, Dryden, Swift, Prior, Sterne, Fielding, Smollett, and a score of writers – all containing passages far more objectionable than any that can be picked out from the Zola translations published by me.

I admit that the majority of the works above referred to were written many years ago; still they are largely reprinted at the present day – at times in editions de luxe at a guinea per volume, and at others in people’s editions priced as low as sixpence – so that while at the period they were written their circulation was comparatively small, of late years it has increased almost a hundredfold.

Now, however, that the Government has thought proper to throw its weight into the scale, with the view of suppressing a class of books which the law has never previously interfered with – otherwise the works I have quoted from could only be issued in secret and circulated by stealth – circumstances are changed, and I ask, for my own and other publishers’ guidance, whether, if Zola’s novels are to be interdicted, “Tom Jones” and “Roderick Random,” “Moll Flanders” and “The Country Wife,” “The Maid’s Tragedy” and “The Relapse,” in all of which the grossest passages are to be met with, will still be allowed to circulate without risk of legal proceedings.

In the extracts now submitted to your notice, and which you must be well aware could be multiplied almost a hundredfold, I have made no selections from cheap translations of the classics with their manifold obscenities – in a single epigram of Martial’s, greater impurity is to be found than in M. Zola’s twenty novels – nor from popular versions of foreign authors, whose indecency surpasses anything contained in the English versions of “Nana” and “The Soil,” and who, unlike M. Zola, exhibit no moral tendency whatever in their writings.

Is life as it really exists – with the vice and degradation current among the lower classes, and the greed, the selfishness, and the veiled sensuality prevalent in the classes above – to be in future ignored by the novelist who, in the case of M. Zola, really holds the historian’s pen?”

HE PLEADED GUILTY

The case ran parallel in the newspaper reporting of it with the Jack the Ripper murders of Mary Nichols, Annie Chapman, Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes, and was, in many ways, overshadowed by events in Whitechapel.

Ultimately, Henry Vizetelly opted to plead guilty and was fined £100, despite the fact that numerous writers and publishers had taken up the cudgels on his behalf.

What the case did do, however, was to feed the suspicion that the ready availability of cheap editions of perceived obscene literary works was behind a decline in the morals of the lower classes, and, in consequence, it ignited a debate as to whether censorship should be enforced to stop impressionable young people from being able to acquire such works.

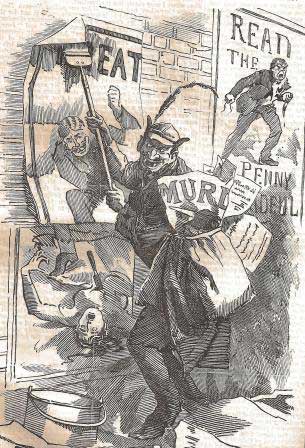

In turn, this led to arguments as to whether the increase in violent crime – as typified by the Jack the Ripper murders – might not be being fuelled by the glorification of crime and criminals in the penny dreadfuls and the cheap newspapers that had begun to proliferate in recent decades.

A CENSORSHIP OF MORALS

The St James’s Gazette, on Thursday 1st November, 1888, reported the outcome of the Vizetelly case, and raised the issue that, if there was to be suppression of the works of authors such as Zola, should there not also be suppression of the glamorisation of criminals in low-class fiction, and even of the reporting of crime in the popular press:-

With the literary aspects of the question raised by the prosecution of Mr. Vizetelly for publishing obscene books, we do not propose to meddle. Some literary persons, well qualified and ill-qualified, were ready to take up the cudgels for Mr. Vizetelly, for Zolaism in general, and for La Terre in particular.

But Mr. Vizetelly cut away the ground from his apologists by pleading guilty and promising not to repeat his fault.

ART AND MORALITY

Nor shall we touch the question – raised and debated a hundred times, but never likely to be settled – how far Art is concerned with Morality. Is art above morality? or beneath it? or does it stand on an altogether different plane?

What we propose to ask is a much more practical question. Is there to be moral censorship of literary work? Hitherto the practice has been to tolerate or to ignore every publication which was not an open defiance of decency.

Mr. Bradlaugh and Mrs. Besant were prosecuted because it was believed – rightly or wrongly – that it was their intention to corrupt public morality.

A later and a far graver offence against decency was allowed to pass almost unchallenged; and the immunity extended to the publishers of a newspaper is, no doubt, a partial explanation of the increased audacity which has been recently exhibited by the persons who traffic in the obscenities of native and foreign fiction.

The desire not to advertise them, and the probability of unsuccessful prosecution have influenced many persons who detest them and would gladly suppress them, to leave them quite alone.

We are not sure that this was not the wiser course, nor are we sure that the punishment of Mr. Vizetelly will have none but good effects, even in that sphere of morality which is intended to benefit by it.

THE GLORIFICATION OF MURDER

But purity is not the whole of morality.

If the books which tend toward lubricity are to be suppressed, why should the books be allowed to go free which glorify murder, burglary, and highway robbery? Why is bloodshed and dishonesty to be preached on the streets if sexual morality is to be guarded by legal procedure?

It is quite as important that the minds of boys and girls should be kept from unnecessary contact with crime which injures the community as with dirtiness which has no influence except upon the personal character.

For the young persons who have been taught to read trash at the public expense, it is debasing to read the gross amours of French peasants; but it is equally debasing for them to study the thrilling deeds of Pearce the house-breaker and Jack the Ripper.

DIRT FICTION

If dirt fiction is to be suppressed, why should we not take one step further and check the sensational histories of actual crimes? This is a course which few people would be as yet prepared to recommend. But yet it is in a way the logical consequence of yesterday’s proceedings in the Central Criminal Court, If we are to have a censorship of public morals, let it at least be complete and thoroughgoing.

But we are not sure that the nation would not be ready to support some kind of censorship if it had any kind of certainty that its good effects would counterbalance the evils which it certainly would bring about.

LEGAL CONTROL OVER PRESS REPORTING

It is certainly a singular and significant sign of the times that it should be possible to discuss the question at all. Yet discussed it will be.

It may be said that to exercise a legal control over the publication of accurate reports of real crimes and real trials is to strike a blow at the publicity of English justice. So it is, and the objection is grave; but so is the evil which we have to deal with.

THE CHILDREN OF THE LOWER CLASSES

Until what is called education had become nearly universal, the possibilities of harm which were latent in printed matter had not attracted public attention. The children of the lower classes read with difficulty, and did not read for amusement.

That has all been changed.

With the penny novel, the penny biography, and the cheap newspapers, an evil and a danger which had been limited has become universal.

We have now to face an agent of moral corruption, no longer confined to persons willing and ready to be corrupted, but obtruding itself on everybody, young and old, rich and poor, even upon those who would be glad to escape from temptation.”