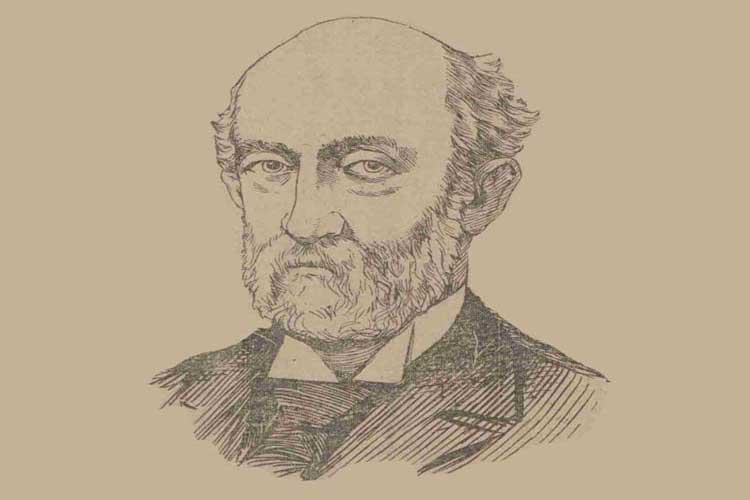

Inspector Henry Moore (1848 – 1918), was one of the officers who, in September, 1888, was sent from Scotland Yard, the headquarters of the Metropolitan Police, to supplement the East End detective force who were investigating the Whitechapel murders.

He worked as a subordinate under Inspector Frederick George Abberline, until, in August, 1889, Abberline was recalled to Scotland Yard to head up the Cleveland Street scandal investigation, whereupon Moore was given command of the on the ground investigation into the Whitechapel murders.

He would remain in charge until 1896, when, with the certainty that the crimes had stopped, the hunt for the murderer was wound down.

THE LEAD JACK THE RIPPER DETECTIVE

As the lead detective on the case from 1889 to 1896, and as a member of the team of detectives who pursued the ripper throughout the autumn of 1888, Moore’s opinions on and recollections of the hunt for the killer would be of great interest to all students of the case.

As it happens, in August, 1889, Moore gave an interview to the American journalist Richard Harding Davis (1864 -1916), who came to London to research an article about the Whitechapel murders.

MEETING WITH ROBET ANDERSON

Carrying a letter of introduction to Dr. Robert Anderson, the Assistant Commissioner, and the head of the Criminal Investigation Department, Davis made his way to Scotland Yard, where Anderson met with him.

Davis, it would appear, was looking forward to some juicy revelations about crime rate in London, but Anderson was quick to disabuse him of the notion that the metropolis was a hotbed of villainy.

According to Davis’s subsequent article, Anderson began their meeting with an apology. “I am sorry to say on your account and quite satisfied on my own that we have very few criminal “show places” in London. Of course, there is the Scotland Yard Museum that visitors consider one of the sights, and then there is Whitechapel.

But, that is all.

YOU OUGHT TO SEE WHITECHAPEL

You ought to see Whitechapel. Even if the murders had not taken place there, it would still be the show part of the city for those who take an interest in the dangerous classes.

But, you mustn’t expect to see criminals walking about with handcuffs on or to find the places they live in to be any different from the other dens of the district. My men can show you their lodging houses and can tell you that this or that man is a thief or a burglar, but he won’t look any different from anyone else.”

Davis observed that he had never found that they looked any different from any one else.

“Well,” replied Anderson, “I only spoke of it because they say, as a rule, your people come over here expecting to see dukes wearing their coronets and the thieves of Whitechapel in prison-cut clothes, and they are disappointed. But, I don’t think you will be disappointed in the district. After a stranger has gone over it he takes a much more lenient view of our failure to find Jack the Ripper, as they call him, than he did before.”

OFF TO LEMAN STREET POLICE STATION

Having arranged for Davis to be shown around the area by a high ranking officer, Anderson bade him farewell, and the journalist headed to the East End, and he arrived at Leman Street Police Station, at 9 o’clock at night, where he found the entrance to the station barricaded with several crossings of red tape.

“It was very different from the easy discipline of an American police station,” he later wrote, “and from the nights when, as a police reporter, I walked unquestioned into the roll room and woke up the sergeant in charge to ask if there was anything on the slate, and to be told, sleepily, that there was “nothing but drunks.””

SUPERINTENDENT ARNOLD

On his being admitted to Leman Street Police Station, he met with Superintendent Thomas Arnold, who introduced him to the man who was to be his guide, “a well-dressed gentleman of athletic build, who, Arnold told him, was Inspector Moore, the chief of the detective force that has, since April, 1888, covered the notorious district of the Whitechapel murders.”

Could there have been a better qualified guide to take him around the East End haunts of Jack the Ripper?

UNFAIR CRITICISMS

As the Whitechapel murders scare had gathered momentum over the course of the previous twelve months, the Metropolitan Police had found themselves facing hostile criticism, not only from the British press and public, but also from some of their overseas counterparts.

Some of the criticism had been unfair, and had been made by people who had no understanding of the problems that the warren-like complexity of the district confronted the investigating detectives with.

Inspector Moore, was anxious to put the record straight, and he began holding forth on these criticisms as he and Davis left the police station and set off through a network of narrow passageways, which, the journalist later described as being, “as dark and loathsome as the great network of sewers that stretches underneath them, just a few feet below.”

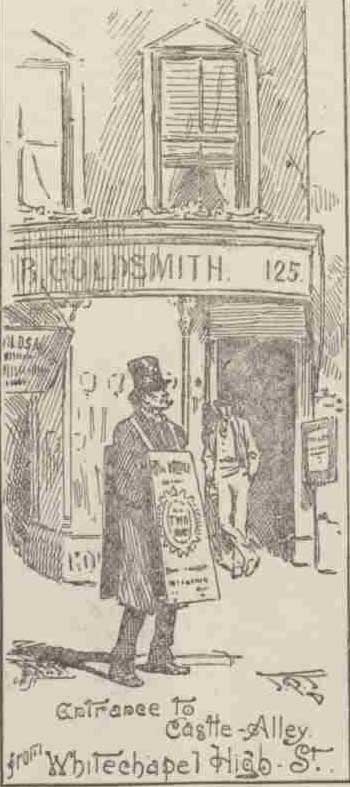

CASTLE ALLEY AND AN APOLOGY

They arrived in Castle Alley, which, in July, 1889, had been the scene of the murder of Alice McKenzie, and Moore told Davis how it was here that he had been able to elicit and apology from an American police chief who had not understood the unique challenges posed by the labyrinth-like layout of the streets of Whitechapel to the prevention and detection of crime and criminals. Davis later recalled how Moore had told him:-

“The chief of police from Austin, Texas, came to see me, and he offered me a great deal of advice. But when I showed him this place and the courts around it, he took off his hat and said, “I apologise, I never saw anything like it before. We’ve nothing like it in all America.” He said that, at home, an officer could stand on a street corner and look down four different streets and see all that went on in them for a quarter of a mile off.

TWO REGIMENTS OF POLICE

Moore then highlighted the difficulties of policing thoroughfares such as Castle Alley:-

“Now, you know, I might put two regiments of police in this half-mile of district, and half of them would be as completely out of sight and hearing of the others as though they were in separate cells of a prison. To give you an idea of it, my men formed a circle around the spot where one of the murders took place, guarding, they thought, every entrance end approach, and, within a few minutes, they found fifty people inside the lines. They had come in through two passageways which my men could not find.

And then, you know these people never lock their doors, and the murderer has only to lift the latch of the nearest house and walk through it and out the back way.”

A TOUR OF THE DISTRICT

The two men then set off to explore the district, and Moore revealed that they called Whitechapel the three Fs district, which, he informed Davis, stood for “Fried Fish and Fights.”

They paid a visit to a well known lodging house, and Davis was sufficiently disturbed by what he saw to ask Moore if he ever felt nervous for his personal safety.

The policeman handed the journalist his cane by way of explanation.

“It was a trivial looking thing,” Davis later informed his readers, “painted to represent maple, but on close inspection I found that it was made of iron.”

Moore then revealed to Davis how he never really felt unsafe in the district since he enjoyed a certain amount of respect among its criminal classes.

“They wouldn’t attack me,” Mr Moore said, “It’s only those who don’t know me that I carry the cane for.”

THE PLAIN CLOTHES DETECTIVES

One of the intriguing things about the ripper investigation, is the number of plain clothes detectives who were drafted into the area at the height of the scare, not to mention the number of amateur detectives that were out on the streets on the murderers trail. Davis was given a glimpse of some of the nocturnal activities that the police were pursuing:-

“The inspector gazed calmly up and down the street, and then remarked, apparently to a lamp across the way, “Better write; you mustn’t come too often.”

We walked on in silence for half a block, and then I suggested that he was using amateur as well as professional detectives in his search for the murderer.

“About sixty,” he replied, laconically.

PEOPLED WITH SPIES

Although Moore proved reluctant to give away much information about his army of plain clothes detectives, Davis later informed his readers that he had himself spotted them, and he made an observation about them that was a standing joke amongst locals and journalists, that, no matter what disguise the plain clothes detectives adopted, they always wore their standard issue police boots and so were easily identifiable.

As Davis put it:-

“The inspector was non communicative, but I could see and hear for myself, and a dozen times during our tour women in rags, lodging-house keepers, proprietors of public-houses and idle young men, dressed like all the other idle young men of the district, but with a straight bearing that told of discipline, and with the regulation shoe with which Scotland-yard marks its men, whispered a half-sentence as we passed, to which sometimes the inspector replied or to which he sometimes appeared utterly unconscious.

From what he said later, I learnt that all Whitechapel is peopled with these spies. Sometimes they are only “plain clothes” men, but besides these he has half a hundred, and, at times two hundred unattached detectives, who pursue their respectable or otherwise callings while they keep an alert eye and ear for the faintest clue that may lead to the discovery of the invisible murderer.”

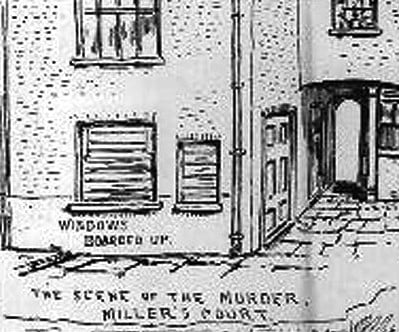

A VISIT TO MILLER’S COURT

One of the locations that they visited that night was Dorset Street, off which Mary Kelly had been murdered, on the 9th of November of the previous year.

The two men actually visited 13, Miller’s Court, the room in which the atrocious crime had taken place, and they even met with the current residents of the room.

Moore, told Davis that he had seen inside Mary Kelly’s room in the immediate aftermath of her murder, and he claimed to have seen the body as it lay on the bed.

It should be noted, however, that the account that appeared in the article appears to have been exaggerated, and certain facts that are given – such as the killer escaping through the window, and the fact that he had hung bits of flesh and body parts around the room, are at odds with the reported facts.

THE WORST OF THE MURDERS

“This was about the worst of the murders,” said the inspector, when they reached Dorset Street.

“He cut the skeleton so clean that, when I got here, I could not tell whether it was a man or a woman. He hung the different parts of the body on nails and over the backs of chairs.

It must have taken him an hour and a half in all. And when he was ready to go he found the door was jammed; and he had to make his escape through the larger of those two windows.

LOCKED IN THE ROOM

Imagine how this man felt when he tried the door and found it was locked; that was before he thought of the window – believing that he was locked in with that bleeding skeleton and the strips of flesh that he had hung so fantastically about the room, that he had trapped himself beside his victim, and had helped to put the rope round his own neck.

One would think the shock of the moment would have lasted for years to come, and kept him in hiding.

But it apparently did not affect him that way, for he has killed five more women since then.

INSIDE NUMBER THIRTEEN

We knocked at the door and a woman opened it.

She spoke to someone inside, and then told “Mister Inspector” to come in.

It was a bare white-washed room, with a single bed in one corner. A man was in the bed, but he sat up and welcomed us good-naturedly.

The inspector apologised for the intrusion, but the occupant of the bed said that it didn’t matter, and obligingly traced out with his forefinger the streaks of blood upon the wall at his bedside. When he had done this, he turned his face to the wall to go to sleep again, and the inspector, ironically, wished him pleasant dreams.”

I rather envied his nerve, and fancied waking up with those dark streaks a few inches from his face.”

THEY MAKE HIS CHANCE FOR HIM

Having held forth on the gruesome scene inside 13, Miller’s Court, Inspector Moore, turned his attention the type of women that Jack the Ripper was choosing as his victims, and made a point that is extremely valid, i.e., it wasn’t the murderer, but, rather, his victims who chose the locations where the murders occurred.

He also revealed the effect that the crimes, and the hunt for the perpetrator, had had on him:-

“What makes it so easy for him” – the inspector always referred to the murderer as “him” – “is that the women lead him, of their own free will, to the spot where they know interruption is least likely. It is not as if he had to wait for his chance; they make the chance for him.

MISERABLE AND HOPELESS

And then they are so miserable and so hopeless, so utterly lost to all that makes a person want to live, that for the sake of fourpence, enough to get drunk on, they will go in any man’s company, and run the risk that it is not him.

“I tell many of them to go home, but they say they have no home, and when I try to frighten them, and speak to the danger they run, they’ll laugh and say, “Oh, I know what you mean. I aint afraid of him. It’s the Ripper or the bridge with me. What’s the odds?”

And, it’s true; that’s the worst of it” The inspector feels his work and its responsibilities keenly. He talked of nothing else, and he apparently eats and sleeps on nothing else.

NO CLUES LEFT

Once or twice he stopped, and pointing to a man and woman standing whispering on a corner, said, “Now, why isn’t that Jack the Ripper?”

Why not, indeed?

When I was in the Scotland-yard museum I expressed some surprise that there were no relics on exhibition of the Whitechapel murders, the most notorious series of criminal events in the history of the world when one considers the civilisation of the city and of the age in which they have occurred, and the detective who was showing me about said, “We have no relics; he never leaves so much as a rag behind him. There is no more of a clue to that chap’s identity than there is to the identity of some murderer who will kill someone a hundred years from now.”

HOAXERS AND LETTER WRITERS

Obviously, at the time, the hunt for the murderer was still going-on, and numerous clues and lines of enquiry were still being being pursued.

But, as Inspector Moore explained, the investigation was being hindered by hoaxers, letter-writers and, on occasion, even by the very detectives who were out on the streets trying to catch Jack the Ripper before he killed again:-

“But they have thought they had clues. They have thought they had the murderer himself perhaps, hundreds of times. Suspicion has rested, so the inspector said, on people in every class of society – on club men, doctors and dockers, members of Parliament and members of the nobility, common sailors and learned scientists.”

WHERE THE MURDERER WAS HIDING

In two squares the inspector pointed out three houses where, he said, he had gone to find him. He told the story to illustrate the degradation of the women of the district, but the point of interest in them to me was that, in a space of two hundred yards, he had found three houses where the murderer was supposed to be in hiding.

This shows that there must have been hundreds of men suspected of whom the public have heard nothing.

MISTAKES AND FALSE CLUES

Inspector Moore said that his own detectives, amateur and professional, would occasionally follow each other for a week with the idea that they were tracking the murderer.

“And then we are so often misled by false clues, suggested by people who have a spite to work off. We get any number of letters throwing the most circumstantial evidence about a certain man, and when we run it out we find the evidence has been cooked up by someone who hates him probably, or some woman whom he has thrown over.

All this takes time and money, and from the nature of our work we can say nothing of what we are doing; we can only speak when it is done.

I have received 2,000 letters of advice from America alone; you can fancy how many I get from this country.

“And then there is the practical joker who sends us letters written in blood and bottles of blood, parts of the human body or the entrails of animals which he says he took from his victim.

It is not an easy piece of work, I assure you. I work seventeen and eighteen hours a day. If I get into bed I think maybe he is at it now, and I grow restless, and finally get up and tramp the courts and alleys until morning.”

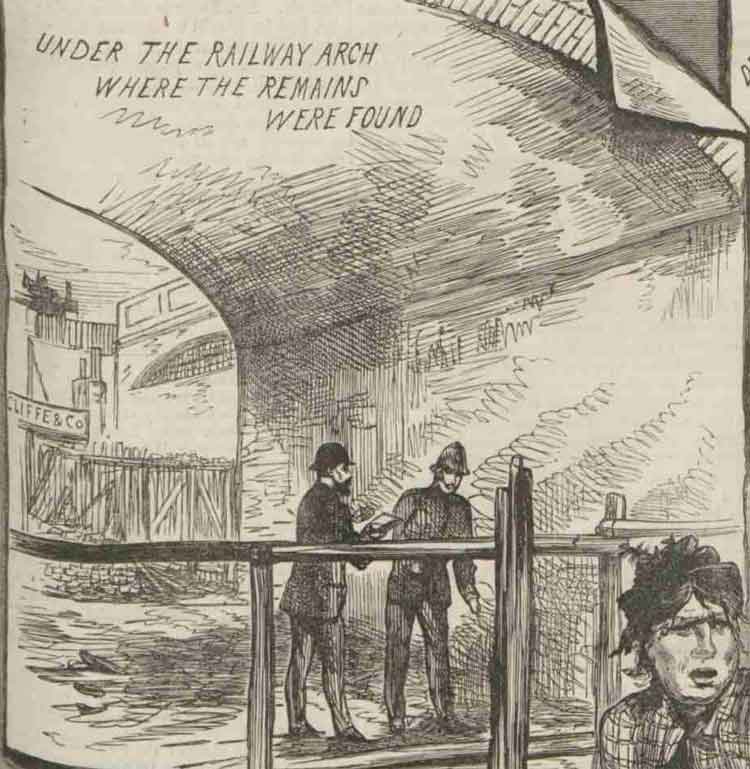

THE END OF THE TOUR

It had been a five hours’ walk through more misery, vice and crime than can perhaps be found in as small a space, less than a square mile, in any other great city.”

As their tour of the area approached its end, and the journalist and the inspector neared Leman Street Police Station, Moore pointed out a location that, in his opinion, would make the perfect spot for a murder to be carried out.

In so doing, he, inadvertently, pointed out the location where the next victim, the unknown lady whose torso was found beneath a railway arch in Pinchin Street, would be discovered, less than a month later.

WHA A PLACE FOR A MURDER

Davis concluded his article thus:-

“There had been only eight murders then.

And, as we neared the station, I remember the inspector’s pointing into the dark arches of the London, Tilbury, and Southend Railway, and saying:-

“Now, what a place for a murder that would be.”

THE PINCHIN STREET ATROCITY

A week later, while I was in mid-ocean on my way back, the body of the ninth victim was found, just under those very arches, and not three minutes walk from the police-station. I don’t know whether Jack the Ripper was lurking near us that night and had acted on the inspector’s suggestion, or whether the inspector is Jack the Ripper himself, but the coincidence is certainly suspicious.

As for myself, although I assented to its being a good place for murder at the time, I can prove an alibi by the ships captain.”

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR YOUTUBE CHANNEL

We produce many videos on all aspect of the Whitechapel murders, as well as the history of policing, crime and of the East End of London. These are available to watch on our YouTube channel.