The people of the 19th century East End of London had fought a daily battle for survival with forces seen and unseen for decades, prior to the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.

Indeed, in many ways, it was the unseen horrors that could most easily strike terror into the hearts and minds of citizens all over London, since they might, at any moment, spill over from the East End, and infect the wealthier parts of the Victorian Metropolis.

THE SCOURGE OF CHOLERA

One of the biggest killers in London during the 1800s was cholera, and its effects on the East End of London were, to say the least, decimating.

Its spread was aided by the unsanitary conditions under which the residents dwelt, and, long before the Whitechapel murders confronted people with another and different type of unseen terror, newspapers were publishing lurid articles that helped create an image of the East End, in the minds of the populace at large, as being an unwholesome district from which little that was good could ever emerge.

THE CAUSE AND EFFECT OF THE EPIDEMIC

One such article appeared in the Penny Illustrated Paper on Saturday, 11th August, 1866:-

“Over again, by illustrations and articles, we have called attention to the foul hotbeds of cholera existing in the poorer quarters of London.

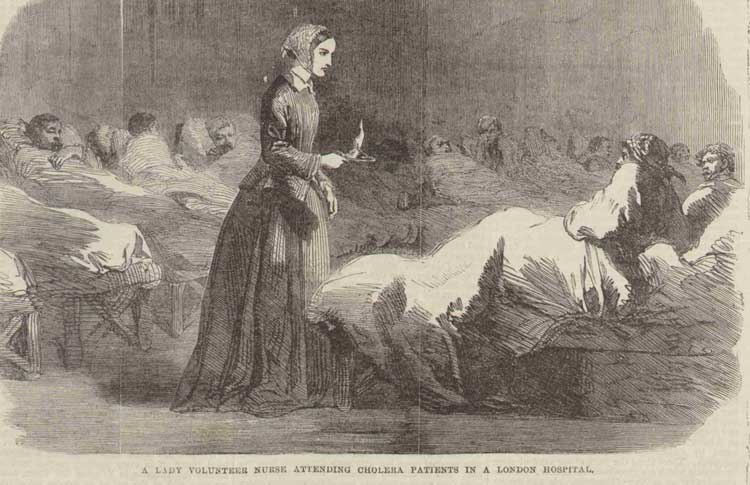

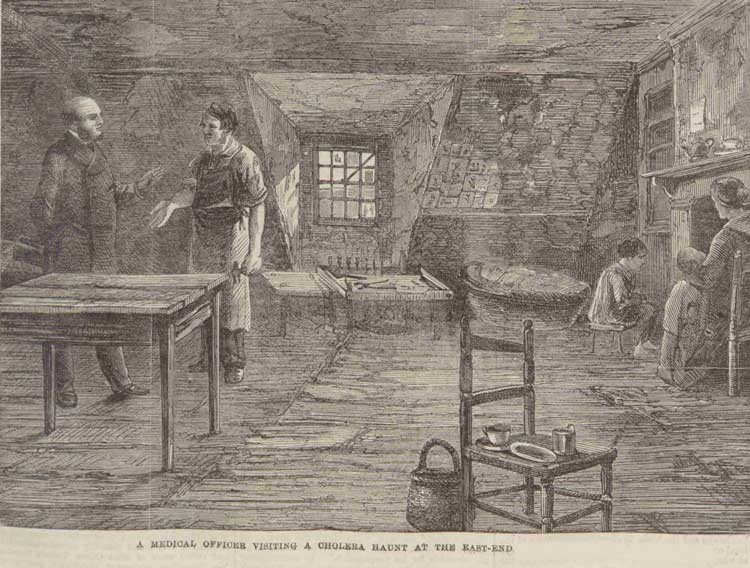

We now print two Engravings depicting in some way the cause and effect of the dread epidemic; and in connection therewith we quote from some recent reports in the Daily Telegraph, which has done the public good service in bringing to light the scenes of squalor at the East-End and the praiseworthy loving kindness of the managers and nurses at the London Hospital.

The most distressing of all the misfortunes of life are those which to human sight have no certain motive or end – which seem to follow no law, to pursue no plan, to suggest no hope nor lesson.

THE MYSTERIOUS TERROR

It is not so with the cholera in this year of 1866.

To watch its mortality is to witness the plain sequence of cause and effect, which, however stern the monition, does not appal us with the grim features of any mysterious terror.

Untrapped drains, reeking cesspools, stagnant ditches, bad food, poisoned water these are the weapons of the enemy, and where these are readiest to his hand the field is most thickly strewn with the slain.

Rifled cannon and needle-gun, shot, shell, bayonet, or sabre could not do the work of death more surely.

THE DISEASE IS ADVANCING

From all signs which are to be read in traversing the infected districts, it would appear that the disease is advancing with unequal steps, but with main directness, from the east.

Nor should any temporary lull be regarded as more than a perturbation in the face of the warnings which former outbreaks have given us.

The concurrent evidence of medical men, within and without the hospital, in this wide neighbourhood is that the cholera of 1866 is more malignant than that of 1849; and if we refer to the records of that calamitous year we shall see that August and September were the two chief months of an awful mortality. There was a fearful leap from June to July, the rate of deaths rising suddenly from 428 to 3239 in London alone.

The advance from July to August brought the figures to 6861; and September showed only a reduction to 6043, though in October the number sank from thousands to hundreds again.

A LOOK AT MILE END

Let us see what has been done in the neighbourhoods surrounding the London Hospital, taking Mile-end first, as being nearest.

We shall find here less to lament and less to condemn than in other districts yet lying open to us – districts into which the first glimpse is suggestive of an appalling task, when their inspection shall be fully undertaken.

OLIVER TWIST AND JACOB’S ISLAND

It is now very little short of thirty years since, in a then flourishing magazine, Mr. Charles Dickens drew such a picture of Jacob’s Island as might almost have been expected to fright even that daringly foul and fetid isle from its impropriety.

The story of “Oliver Twist,” if it did nothing better, did at least excellent service in laying bare the hidden nuisances of London; nor can it be said that the literary Hogarth exceeded truth in his graphic essays; although, at a period long subsequent to their production, a sapient vestryman contended that the book in which the pestilent alleys of Jacob’s Island were described was a work of fiction, and that, argal, the description itself was merely imaginary, and “there wasn’t such a place.”

If there really were no such places, London might be able to give cholera a wider berth; but, unhappily, there are a great many of them every bit as bad as Jacob’s Island.

GROSS AND FILTHY ABUSES

As we have intimated, Mile-end is better off than some adjacent spots; for example, than St. George’s in-the-East, than Bethnal-green, than Whitechapel, than Spitalfields, and than Ratcliff-highway; but truly there is enough for energetic management and medical skill to achieve in purging even Mile-end of its gross and filthy abuses.

DR. CORNER THE MEDICAL OFFICER

The guardians have done well to appoint, in lieu of an old servant whose years and infirmities have carried him past his work, a younger and an unquestionably able medical officer of health, in Dr. Corner, whose first work has been to report on the insalubrious state of several parts of the large hamlet of Mile-end.

He tells them of open cesspools, of untrapped drains, of deficient water supply, accumulations of refuse and filth of all kinds in open spaces, brought thither from the City sewers, and from many, indeed countless sources; and shows them that, where these nuisances exist, cholera is most fatal, diarrhoea most abounding.

“Only the most prompt action and employment of a large and efficient staff,” he says, “can check the advance of disease in a district where there exist in abundance all the elements for its propagation.”

THE MEASURES BEING TAKEN

In praiseworthy accordance with the advice thus given them, the vestry board have appointed five medical visitors, with assistants, to each ward, and have taken other steps to meet the great emergency.

Dr. Corner himself went to the East London Water Company, and urged the necessity of two supplies of water each day instead of one; and his application was met, we are glad to record, with ready acquiescence.

Another suggestion, to which we believe the company are not inclined to lend so willing an ear, is that all cisterns and butts pertaining to the poorer houses in the district should be bodily done away with, and the water supplied directly from the main.

This is a scheme the consideration of which may, perhaps, be allowed to stand over for a time; and, meanwhile, it is some satisfaction to know that the inhabitants houses, wretchedly wanting in all systematic drainage, will be enabled to flush their poor apologies for sewers with an adequate supply of clean water.

A CHILD WITH CHOLERA

The statement of the new acting medical officer, that the ravages of cholera are principally found where, indeed, common sense might first look for them – in the very hotbeds of disease – appeared to be somewhat substantiated one evening last week by a case of cholera which he, in company with one or two other gentlemen, personally attended.

The sufferer was a child, quite a baby, and it was lying on it’s mother’s lap in a poor, though not a disreputably dirty room in a court called Govey’s-place.

The little thing was stripped and wrapped in warm blankets, with a mustard poultice on its stomach. Its eyes rolled hither and thither, in consciousness; and indeed the poor little sufferer was conscious, and actually obeyed the doctor’s demand that it would show him its tongue. This member was quite cold, cold as the surface of the body, and the lips were blue as pale indigo.

Having prescribed brandy-and-water as the only remaining means of restoration, the doctor and his companions went downstairs, to a place right under the sick-room.

THE SEWAGE COVERED FLOOR

This place is indescribable in any language ordinarily adequate to picture squalor and to suggest stench.

It was the workshop of a pipemaker, and it had a refuse hole, open privy, and cloacan chaos, in which all that was perfectly distinguishable was an untrapped drain in the midst of a broken, sunken, swampy, brick or stone floor, concerning which the pipemaker’s voluntary evidence was that the neighbouring drain overflowed upon it.

This hotbed or sink of deadly disease was on a level with the living-room of the pipemaker’s family, and, as we have said, was immediately below the room in which the sick child was being hopelessly tended.

We have left much untold regarding a neighbourhood better off in every sanitary respect than those around it.

THE HORRORS OF GLOBE ROAD

There is, in Mile-end Old Town, near its confines, and at the end of an avenue called Globe-road, one of the most hideous heaps of filth, that might deter any man from speaking of it by the obvious suggestion that the least he could say would never obtain credence.

We believe sincerely, and on good warrant, that the parish authorities are awakened to the duty of cleansing away this abomination and many others of its kind; but how, in the name of wonder, could they ever have slumbered with such uncleanliness assaulting their nostrils.”