One thing that is certain about the Whitechapel Murders is that they brought to the area people who would never have dreamed of venturing into the streets of the East End had it not been for the Jack the Ripper crimes.

Journalists, philanthropists and amateur detectives, not to mention the just plain curious, found themselves drawn to the district where the murders were occurring to see, first hand, if the neighbourhood was actually as bad as it was being portrayed in the media.

Many of them found that, in some ways, it was worse!

Many of these visitors to the area,wrote accounts of their experiences and, in so doing, they left us with little snapshots of the East End of London as it was in the late 19th century.

Reading some of the accounts, you can’t help wonder if a little poetic licence wasn’t being deployed, as writers tried to outdo one another with more and more lurid accounts of East End life.

In the wake of the murder of Alice McKenzie, which took place on the 17th July 1889, for example, the New York Herald published an article written by a correspondent who had ventured into the area by night, accompanied by a “member of the Government” and a “special detective.”

The account was reproduced in the South Wales Echo on Monday 22nd July 1889, and it makes fascinating, though disturbing, reading, albeit it is difficult to ascertain just how much exaggeration the article’s author employed to make his piece even more hard hitting.

EXPLORING EAST-END SLUMS

NIGHT IN THE LOATHSOME DENS

OF THE WHITECHAPEL DISTRICT

HAUNTS OF MISERY, WOE AND VICE

“How does the Whitechapel district appear to a stranger in London?

That is what I went to see (says a correspondent of the New York Herald) one Saturday night.

In company with a member of the Government and a special detective, I took a four-wheeler and drove late at night down by St. Paul’s, past the Bank of England, and on through Cornhill, where, turning to the left, we followed up Bishopsgate to the famous underground drinking dive known in history as Dirty Dick’s.

The detective thought it would be interesting to begin the evening with a visit to this celebrated place. It dates back nearly a century, and 70 years ago Dirty Dick was one of the characters of London. Charles Dickens’ Household Words devoted a sketch and a poem to Dirty Dick’s life and peculiarities.

The rules that governed his establishment were: –

“That no person is to be served twice. No person is to be served if intoxicated. No error admitted or money exchanged after leaving the counter. No improper language permitted. No gambling allowed.”

THE FAMOUS HISTORICAL CELLAR

Into this famous historical cellar we entered. Every foot of space was occupied. Men, women, and children were packed together like fish, all drinking, smoking, and swearing, at intervals telling loud stories, while, in the corners, sitting on benches or staggering against the walls, were women, old and young, in various degrees of intoxication,

One miserable creature, evidently in the last stages of sanity, grinned hideously as she leaned over the bar with a wee baby in her arms, begging for another drink, as she had already spent her last penny.

THE SKELETONS OF VERMIN

Along the walls, above the bottles of the bar, were the skeletons of rats and mice and other household vermin, including several cats and dogs.

They were found in the hollow walls when the old building occupied by Dirty Dick was demolished several years ago to make room for the present structure.

To a stranger the dive seemed a filthy den of vice and disease, but on our return from Whitechapel it seemed a very respectable place.

THE BLUE ANCHOR TAVERN

The next stop was made at the Blue Anchor Tavern, further down towards Whitechapel.

To sporting men it is one of the most celebrated places in England, for it is the headquarters of the professional prize ring.

The landlord, Tom Symonds, was at home and showed us over the place.

He is the treasurer of the London Prize Ring, is an ex-champion boxer, and for many years his house had been the training school for the most noted pugilists of the world.

It was here that Jem Smith and dozens of other celebrities took their first lessons in the manly art for professional boxing.

Jem Goode, another ex-champion, who once fought in the United States, dropped into the big billiard hall which is used for boxing once or twice a week.

The rooms are decorated with full-length portraits of the principal prize-fighters and sports of the world.

A buxom young woman with a motherly smile stood behind the bar and served out drinks in the old-fashioned English style of fifty years ago.

THE SLUMS OF WHITECHAPEL

From Tom Symonds Blue Anchor Tavern it is but a short ride into the slums of Whitechapel.

It should be explained for the benefit of those unfamiliar with the geography of London that the Whitechapel district is nearly north of the Tower of London, on the Thames.

A few blocks further down the river are the famous London Docks.

Many of the lower classes of men employed along the river and the numerous water thieves of the wharves live up in Whitechapel.

A hundred years ago, in the time of George III, Whitechapel-road was just outside the eastern walls of London – a sort of suburb for the poorer classes who had little money to pay for rent.

Now it is the centre of a vast and populous district with well-paved streets and alleys – thanks to modern improvements – cutting the district in every direction, with horse, railway, and bus lines following the principal streets, which in olden times were the King’s highways.

Vast warehouses, private and bonded, and manufacturing establishments rise darkly and silently in the night on the borders of the slums.

Then there are big breweries, hospitals, cemeteries, almshouses, and other unpleasant institutions not far away.

A surprising feature of the neighbourhood is that well-lighted streets with tramways and bus lines lie but a few squares away from where the Jack the Ripper murders were committed.

HORRIBLE DENS

A visitor walking up Whitechapel-road would little dream of the horrible dens within a stone’s throw of the brilliantly lighted shops.

Only the policemen on duty there recognise the flashily-dressed men and women who hurry along the pavement as the worst types of London thieves and murderers.

Their restless eyes and scarred faces haunt one long after he takes the second look into their villainous countenances.

It was but a few minutes after the detective turned off the Aldgate-road that we found ourselves in a dark crevice-like lane, with the darkest and most forbidding buildings rising on every side of us.

The streets are as well paved as Broadway, in New York, but some of them are not more than 5 feet wide; and when we entered Petticoat-lane, celebrated among thieves from Cheyenne to Australia, all the world seemed cut off.

FEELINGS OF LOATHING AND HORROR

A feeling of indescribable loathing and horror came over one as he got sight of the scenes within the tenements.

The lane is the headquarters of the most dangerous thieves in Europe.

Every class and nation is represented.

Low Jews, Gentiles. convicts, and prison birds of every grade swarm the place like vermin.

“For a Saturday night scene the region about Petticoat-lane has no equal on the globe,” said the detective.

At every few steps were passage ways leading out of the lane, like tunnels in a mine. No cave could be gloomier or more forbidding and foreboding.

As we walked up the long black alley one of the Government officials said, “You see Dickens did not exaggerate.”

People unfamiliar with these districts think that Dickens drew his characters from his imagination, but this man was right – the Smikes and Oliver Twists, the Fagins and the Dick Swivellers, were as thick as flies.

An ordinary, decently-cared-for child would live about three days in such a place, yet there were hundreds of children hardly able to toddle that darted in and out of the passage ways like rats.

AN OVERWHELMING ATMOSPHERE

The atmosphere was thick and foetid, the fog hung over the alleys like lead, and the few scattering jets of gas burning along the lane were hardly visible ten steps away.

After walking through the neighbourhood for five minutes it seemed as if we had been in the place a month; the world and its green fields and its beautiful cities seemed blotted from creation.

As we passed along, heads were poked out of the little holes leading into dark courts, and then they were pulled back again, the childish owners seeming to vanish through the walls.

Dark-faced, scowling men always planted themselves in our way just ahead, but disappeared, like shadows, at a sign from the detective.

Behind us came beggars and thieves.

Women with streaming hair, and babes in their arms, followed with piteous tales and cries for money.

They, too, were thieves and beggars, and the detective said the worst of the lot.

A COMMON LODGING HOUSE

We made a quick turn around a corner, doubled on our course, and encountered one of the thousands of common lodging houses of the Whitechapel district.

There sat the same women, with somebody’s babies, blaspheming and drinking spirits with the bullet-headed infants hanging over their shoulder, like bundles of rags.

Others were singing ribald songs in hoarse, drunken voices, while the men laughed and joined them in the night’s carousal.

This Whitechapel district is a vast city of vice and poverty.

NOT ENOUGH POLICE

London, with its five million of inhabitants and its colonies of criminals, representing the most vicious classes of Europe, is a monstrous problem for any Government to solve.

As we walked down those gloomy lanes and crawled through the underground passage ways among the depots of stolen goods where fortunes disappear in a moment, where men’s lives go out like a candle, I exclaimed aloud, “No wonder it requires 15,000 policemen in London.”

The Government official said, “We have only half enough police. We ought to have 25,000 or 30,000.”

In the presence of the intricacies of the Whitechapel slums, the thousands of winding passage ways, the tiers of bedrooms no larger than cells in a prison, the scene gave one an idea of why the Whitechapel assassins have not been discovered.

One might as well look along the docks of London for the rat that stole his cheese as to hunt for a criminal in this place.

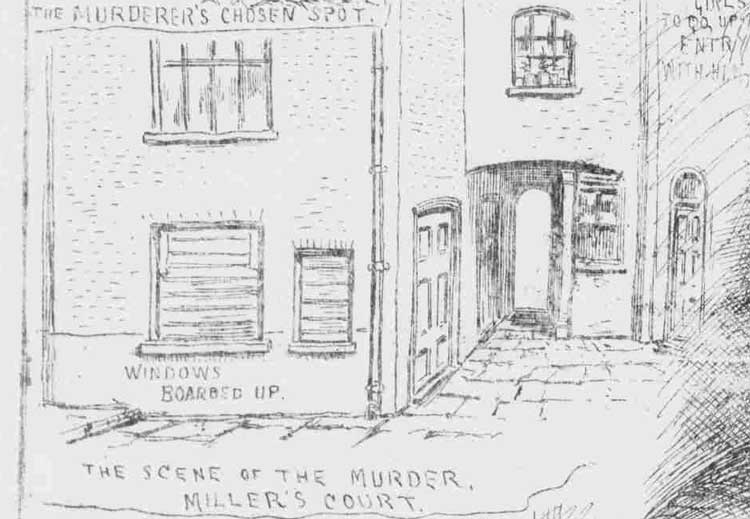

THIS IS MILLER’S COURT

Turning out of a lane, through a dark passage-way in to a little area, and standing beside a small addition, built onto the back of the other houses, and pointing to the boarded windows, the detective said, “In there is where murder number seven was committed.”

While we were looking at the place, and wondering which way the assassin ran after he had killed the poor woman, Kelly, little, yellow-haired children came into the court and listened with a curious boldness as if we were about to open a box of valuables, and there would be a chance for them to steal.

INTO OSBORN STREET

In Osborne-street, where the first of all the murders was committed, and the victim unknown, the White Chapel, which stands in the very middle of Whitechapel-road, is almost in sight.

A walk of a few steps from the horrible place leads one to the open thoroughfare, where the jingling bells of the horse cars are heard, and the chimes of White-chapel ring out on the night air as they do in Christian lands where thieves and murderers are not so near civilisation.

A SURPRISE IN GEORGE YARD

At George’s-yard, Commercial-street – not Commercial-road – the buildings are thick and heavy-walled, entirely fireproof, with arched floors and iron joists.

Yet they are but tenements for the lowest of humanity, and are let as lodgings for men and women indiscriminately it is said.

In all these places there is no attempt made to separate the children from the full-grown thieves and abandoned women.

As I stood in George’s-yard, looking up at the balcony where the poor woman was found with strips of her remains tied round her neck, I turned and saw lights gleaming in a large building separated from the court by a high fence.

On inquiry I found it was a large hall where a much talked about black and white art exhibition was being held.

It seemed incredible that an institution reflecting the light and genius of the 19th century could actually exist and be filled with cultivated men and women, with its windows looking down into the very purlieus of London. The innocence of youth is destroyed by robbers and professional beggars under the very eaves of Christian institutions on one side and breweries and almshouses on the other.

THE PARADOXES OF WHITECHAPEL

We next came to the celebrated Frying-pan Tavern, which is the rendezvous of dissolute characters of the lowest type.

We enter the little room where only “first-class” customers arc served.

In spite of the detective’s efforts, a couple of young thieves got into the room, and proceeded to order “bitter” for two, apparently as an excuse to be on hand should there be chance to steal a watch or cut a throat.

The woman behind the bar was very civil and the place looked as neat as many a saloon in America, but the people who occupied the benches were a study for a painter.

Here, as elsewhere, were women and girls, brazen, leathery-cheeked creatures with bright, suspicious eyes, quick movements, hoarse voices. and gibbering laughs.

The detective informed us that it was a dangerous place, and that two policemen were always kept near the door.

On Saturday nights everybody is at home, and the beggars come in to divide up their spoils, and to hold their weekly revels.

Then the big British officers are very careful about getting mixed up in any rows.

Many a time the policeman, he said, had been thrown down and kicked unmercifully by the crowd, who would yell, “You have got him down now; give it to him until he can’t squeal.”

“They don’t know what mercy is,” said and outside officer, coming up while we were talking.

From the time we entered the street, and while we were in the tavern, tough-looking characters were on watch, like sentinels on each side of the door up and down the street, hoping to get a chance to raid us and steal something should a fight occur.

When strangers come around, these thieves and receivers of stolen goods swarm from the holes in the walls, like wolves from their dens, and a man is as hopeless among them as a child is in the jaws of a crocodile.

ANNIE CHAPMAN’S MURDER SITE

In Hanbury-street, in a brick yard, with dry goods boxes piled up far above the fence, is where Annie Chapman was found with her throat cut, and her body mutilated on the 8th of September 1888.

A RESPECTABLE LOOKING BOY

A bright young lad with fair hair, mild blue eyes, and a good face explained the circumstances of how the body was found – all of which has been told.

He said he had been at school, and he looked like a respectable boy, but all around him were thieves and cutthroats, and, as he stood there in the gloom of the night holding a candle aloft, it was a sight fur missionaries to weep over.”