In 2014, as technology continues to make great leaps forward, and with computer games, films and television finding ways to treat us to ever more realistic and graphic depictions of violence, there are constant calls for the more extreme elements of these “entertainments” to be curbed, as constant exposure to them might lead children and teens to imitate the hostile behaviour they have witnessed on screen.

Interestingly, a similar argument was raging in 1888, at the height of the Jack the Ripper murders, as society struggled to come to terms with how an individual could perform such atrocities for no other reason than for pleasure.

On Saturday September 22nd 1888, The Times published a letter in which the writer pointed out that “it has long been the custom for provincial newspapers to publish serial stories in their weekly issues, generally of a more or less sensational character. These stories of late have in many instances taken the form of the lives and actions, most highly exaggerated, of notorious criminals….”

The writer went on to opine that, “It is only those whose duties cause them to be mixed up with the lower and criminal classes who can really appreciate how great is the evil influence of this pernicious literature and how eagerly it is sought after.”

The writer then informed his readers that “Not long since some lads, children of honest parents, committed two burglaries; it was clearly shown by their own confessions that that they had been instigated to do so by reading “Dick Turpin, The Prince of Highwaymen.” A youth of about 18, of miserable physical power, when arrested for larceny bit the constable’s thumb and said “I am as game as Charley Peace, and I will do as much as him before I die.” The history of the “King of Criminals” was being published at the time by one of the local papers. Many similar instances could be furnished.”

The letter’s writer then turned his attention to the murders that were then taking place in the East End of London and observed that, “It is, to my mind, quite possible that the Whitechapel murders may be the fruit of such pernicious seed falling upon a morbid and degraded mind.”

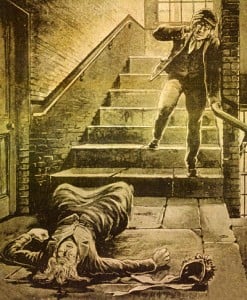

On that same Saturday The Illustrated Police News wondered if the public “…shouldn’t feel indebted for the horrible crimes in Whitechapel” to the “…highly-coloured pictorial advertisements to be seen on almost all hoardings in London, vividly representing sensational scenes of murder, exhibited as ‘great attractions'”.

The article went on to observe that “Everyone who walks much about the streets of London, or of any other large town, must have observed that during the last two or three years the illustrated posters on the walls have shown an increasing tendency to be grossly horrible and revolting.”

Having pointed out how “Theatrical advertisements” spare no detail, by depicting the “…fiendish expression of the villain’s countenance as he plunges a dagger into the bosom of the hero…” the News went on to opine that “…In all great communities there are certain to be a number of small-brained creatures, only half human, whose minds, muddled by bad air and bad gin, readily take fire when they are confronted with the ghastly particulars of murder. Such pictures as these produce upon them the same effect that the taste of blood produces upon the tiger.”

The mention of “Theatrical advertisements” is interesting in that there was a lot of controversy at the time over the stage version of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was, at the time, playing at London’s Lyceum Theatre, with American actor Richard Mansfield performing the dual role of Jekyll and Hyde.

His nightly transformations from one to the other were absolutely terrifying his audiences and had led some to believe that his Mr Hyde persona might not be all down to acting, and some were even wondering if Mansfield himself might be responsible for the East End murders.

Laughable as the accusation might seem, the newspapers were beginning to draw a parallel between Mansfield’s stage depiction of the evil Hyde, and the all too real villain who was bringing terror to the East End streets of the Metropolis, as early as the second Jack the Ripper murder, that of Annie Chapman, on the 8th September 1888.

On the day of her murder, the Pall Mall Gazette referred to the perpetrator of the crimes as “Mr. Hyde at large in Whitechapel.” Later in the month, on Saturday 29th September 1888, the St Stephen’s Review was observing that “Between the Whitechapel Murders and the weird performance of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the mental condition of people with highly-strung nerves is becoming very serious…”

On the 10th October 1888, the Philadelphia Enquirer even went so far as to inform its readers that “the police have started the theory that the Whitechapel murders are the result of a case in real life of “Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.”

So, by the time of the second Jack the Ripper atrocity, it is more than apparent that, in the eyes of certain elements of the media at least, the identity of the Whitechapel murderer himself might not have been known, but the motivation for his crimes lay squarely at the door of the way that violence was being glorified and sensationalised by cheap fiction and by the theatre.

In many ways, the same arguments are still being made and, it seems, we are still as uncertain, or perhaps as unwilling, to draw a correlation between the violence in the media and the real thing as we were in 1888?