Sir William Gull (1816 – 1890) is a frequent – and, in my opinion, unjustified – guest on the ever growing list of Jack the Ripper suspects – especially when television and film directors get involved with telling the story. With his links to the Royal family, and his movements amongst the great and good of the Victorian era his allure as a contender for the mantle of the Whitechapel murderer is easy to understand.

But, what was the real Sir William Gull like and, more importantly, how was he perceived by his contemporaries?

A RESPECTED PHYSICIAN

It is safe to say that, reading the various plaudits cast in his general direction by his friends, colleagues and patients. Sir William Gull was a hugely respected physician. If you want to know more about his astonishing career you can read his full biography on this page.

In addition to becoming the Physician in Ordinary to Queen Victoria, he also made a considerable contribution to medical knowledge – for example, he gave ‘Anorexia Nervosa’ its name and treated it with some success. In addition, he advanced the understanding of several other diseases including Myxoedema, Paraplegia and Bright’s disease.

He also championed the role of women in medicine.

According to a newspaper report, published after his death:-

“Sir William always said that his real education had been given to him by his mother, and to the end of his life he would quote a nursery rhyme she had instilled into him:-

If I were a tailor I’d make it my pride

The best of all tailors to be

If I were a tinker, no tinker beside

Should mend an old kettle like me.”

The article went on to say how:-

“Notwithstanding his great ability, he had at the early period of his career a remarkable lack of confidence in his own powers, as is shown in the following incident:- During an examination he was about to leave the room, saying he knew nothing of the case proposed for comment: fortunately a friend persuaded him to return, with the result that the thesis he then wrote gained for him his doctor’s degree and the gold medal.”

MANY POOR PATIENTS

According to the same aforementioned article:-

“…Gull had many poor people among his patients to the last. Late one night, on returning tired from a long journey, the cabman, on receipt of his fare. still held out his hand with the money in it, hesitated, and said – “But could you give me something for my cough?” The man was taken into the house, prescribed for, and sent away happy.”

THE STORY OF A HEART

On another occasion, Sir William Gull had attended a poor patient who was suffering with severe heart disease. It was apparent that nothing could be done, other than make the man comfortable and await his inevitable demise. Following the patient’s death, Gull was extremely anxious to perform a post mortem examination, but it took an awful lot of persuasion for the dead man’s sister to grant the request.

However, she did eventually agree, on condition that nothing was to be taken away.

Gull, therefore, had to conduct his examination with the dead man’s sister – “a strong-minded old maid” – keeping a keen eye on the proceedings. It was obvious to Sir William that it would be nigh on impossible for him to conceal anything from her, nor for him to persuade her to leave the room until her brother had been sewn up, fully intact.

Anxious to secure the heart for further research, Gull deliberately took it out in front of the woman, popped it into his pocket and then, turning to the astonished sister, he fixed her with a steady stare and said “I trust to your honour not to betray me.” According to a subsequent newspaper report, written after his death, “His knowledge of character justified the result, and the heart is now in Guy’s Museum.”

I HAVE NO SPEECH

According to newspaper reports, following his death on the 29th January 1890, almost his last conscious act was to write the words “I have no speech.”

This prompted the Guernsey Star to lament the “never-to-be-forgotten impression of his voice,” which had soothed “thousands of sick folk…by its harmonious charm.” Indeed, William Gull’s manner of speech, so the article remembered, ” was musical to a degree expressing the refined taste and culture of the speaker.”

However, so the article continued, “..its genuine tones were reserved for the suffering poor, wasting on hospital beds or in wretched homes; for the dying troubled with the dark shadows of the awful valley, and the agonised watchers around their couch; above all, and always, for little children.”

Indeed, one former patient recalled how, as a child, a bout of ill health, that his own doctor proved unable to treat, had resulted in his parents consulting Sir William Gull. He recounted how he [the child] “…came trembling into his presence with awful anticipation of new torments, in the shape of cross-questioning, misapprehension and drugs.”

However, as the former patient recalled many years later, “…out of the gloaming came that voice, inviting us fatherly wise to come close and tell all our little troubles…and by that we were gathered within a kind clasp that knew how to draw out childish confidences…”

SECRET CHARITIES TO THE POOR

Sir William Gull was also a great, and often unsung, charitable worker who worked tirelessly for the Victorian poor and, according to another obituary, “his boundless kindness to the afflicted will never be known this side of the grave.” The article went on to remember how:-

“…He used to make one or two persons in his confidence act as his private almoners, and where medicine and advice alone would have been of little use, the secret purse bearers used to follow, with wine and food, sent by the physician where they were needed.

And the rush and hurry of his busiest days would be made to pause, when some unknown sufferer needed the help of sympathising words and kindly counsel. In fact, he never spared himself, but spent strength and time so ungrudgingly for all who claimed them, that the wonder is for how many years the overtaxed brain held on…”

HIS FUNERAL

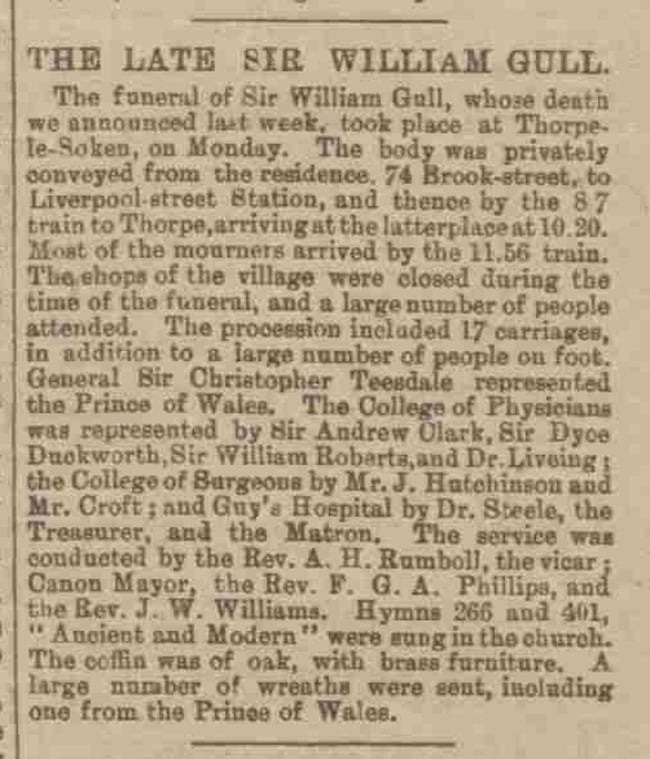

On the day of his funeral, his coffin was transported from his home at 74 Brook Street, in London’s Mayfair, to Liverpool Street Station, from where it was taken by train to Thorpe-le-Soken in Essex. Something of the esteem in which he was held can be gleaned from the fact that the funeral cortège consisted of 17 carriages as well as a large number of mourners who followed on foot.

He now lies buried in St Michael’s Parish Church, Thorpe-le-Soken where, sadly, his grave has attracted the attention of vandals, thanks in no small part to the vandalism that film and television companies have inflicted on his memory by, using little more than ill-informed conjecture and unrestrained speculation, coupled with an awful lot of artistic licence, linking him to five sordid murders in the East End of London that took place in the autumn of 1888.

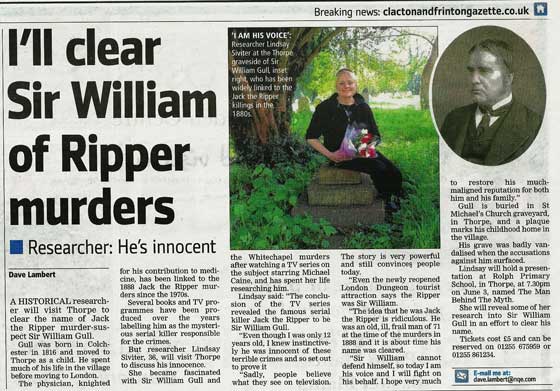

LINDSAY SIVITER’S MISSION TO CLEAR HIS NAME

If you would like to discuss Sir William Gull further, our guide Lindsay Siviter is one of the foremost authorities on him – she is his official biographer – and she is always happy to discuss her latest findings about his life on her tours.