Many of the people of Victorian Whitechapel lived a hand-to-mouth existence, whereby they would buy small quantities of food and provisions, as and when they had the means to do so.

To cater to their needs, the shops around the district would sell provisions in small amounts, often as little as a farthings-worths, or, as it was pronounced in the area “farden.”

POUNDS, SHILLINGS AND PENCE

By way of explanation, in the days of pounds, shillings and pence, a farthing was a quarter of a penny; so two farthings made a half-penny, two half-pennies made a penny, twelve pennies made a shilling, and twenty shillings made a pound.

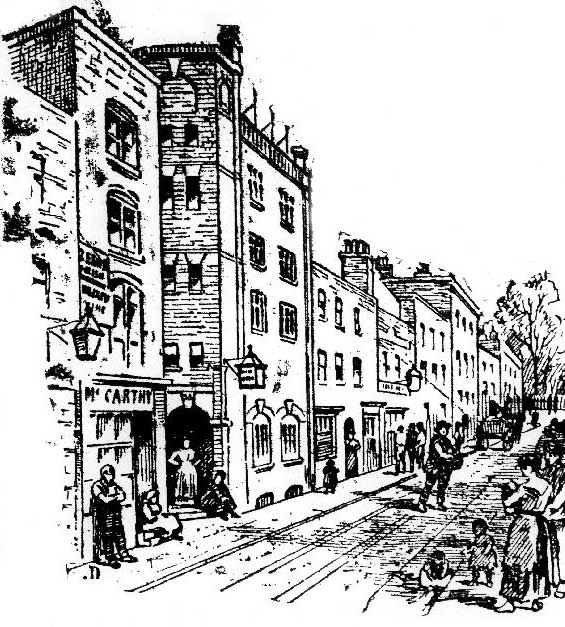

A FARTHING SHOP IN DORSET STREET

On Friday, 6th September, 1889, The Pall Mall Gazette, published the following article by a reporter who had paid a visit to one of the “farthing shops” of the East End.

This one happened to be in Dorset Street, a thoroughfare that, by this time, had become notorious as the location where, the previous November, Jack the Ripper had carried out the murder of Mary Kelly.

It was also the street in which Annie Chapman had been lodging at the time of her murder.

It is a chilling thought that both Annie Chapman and Mary Kelly may well have shopped for provisions at the very shop mentioned in the article.

A VISIT TO A FARTHING SHOP IN WHITECHAPEL

“The window was garnished with a basket of dirty eggs mixed with discoloured chunks of bacon, and sweets, and bread, an article like saveloy run to seed, and the many odds and ends one sees in a “farthing shop.”

The farthing shop is in Dorset-street, a locality made unsavoury by one of the Whitechapel murderer’s feats.

THE PEOPLE OF DORSET STREET

It was nearly eleven o’clock in the morning, and yet on one of the doorsteps two men and a woman were sleeping off a potation.

A gang of impudent-looking young men stood at one corner; they were pointed out as a set of that wretched unnameable tribe who live on women’s shame.

Babies crawl about on all fours in the filth and garbage; sluttish women sit on doorsteps.

This (writes a representative) is the neighbourhood of the “farden shop.”

WHERE DO THE FARTHINGS GO?

The tadpoles on Hampstead Heath formed an interesting study for the fine and ripe intellect of a Pickwick. Would that some statistician could engage himself and interest the world by the study of “Where do the farthings go?”

We miss them so after the limited finance of school days.

A good many of them get to Whitechapel, to this shop in Dorset-street.

INSIDE THE FARTHING SHOP

Among a lot of diminutive packages of soap and tea and sugar, and ha’porths of bacon, there was a saucer of farthings.

I went into the ill-lighted emporium, and a very intelligent young woman, who was serving, told me that they sold nearly everything in quantities of “farthing’s-worths.”

“You can have a farthing’s-worth of tea, and sugar, and soap, and butter and milk. We don’t sell less than a hap’orth of loaf sugar though.”

On the counter, a baby was crowing, and all the time people were streaming in for their farthing’s-worths.

Cooked bacon is sold at a shilling a pound, and “rore bacon,” said the young woman, at seven pence.

THE PEOPLE WHO SHOP

At night the place is a sort of supper club, the members of which all fetch their own provisions from three-halfpence upwards.

Bang went a dirty tin on the counter, and an unkempt child wanted a farthing’s-worth of milk. She put her unclean little nose into it as she walked out.

Then a man came in, and, after much haggling to have the cheapest, he contracted for seven farthings’-worth of bacon. He was a lean and hungry man, long of limb.

Then, in came a woman for a farthing’s-worth of milk and the same of butter.

They evidently breakfast late in Dorset-street. This customer also had a ha’porth of “picallilli,” a peculiar pickle in which it is not exactly possible to distinguish anything but mustard, but it looks chiefly like cauliflower.

Two or three times while I was there the shop filled and emptied, and nearly all the business was done in farthings.

One little boy had a ha’porth of tea-dust.

OPENING HOURS AND PROFITS

The shop opens at six in the morning and it closes at twelve or half-past at midnight. This is the only way that any profit can be got from such poor customers.

Then there are all the packets to be made up ready for customers before the place opens.

This is probably the dearest and the meanest mode of housekeeping anywhere.

THE DREGS OF WHITECHAPEL

The people who live in the street are the dregs of Whitechapel.

Some of them are dockers, but they are the fringe of the worst among the casual labourers.

It explains somewhat how these men, who live from hand to mouth, can hold out so long. If they get a penny from the relief fund there is sufficient to buy a tea with.

With another penny for bread and a penny for coals – for threepence, in fact – the larder is filled, and a cheerful glow permeates the one room that is usually the residence of those who don’t live in the common lodging-houses.”