On the evening of Thursday the 11th February, 1897, Miss Elizabeth Camp was murdered on a train as she travelled to Waterloo Station.

The London Evening Standard broke the story of the atrocity on Friday, 12th February, 1897. albeit the early accounts of her murder gave her name as Kemp:-

SUPPOSED MURDER IN A RAILWAY CARRIAGE

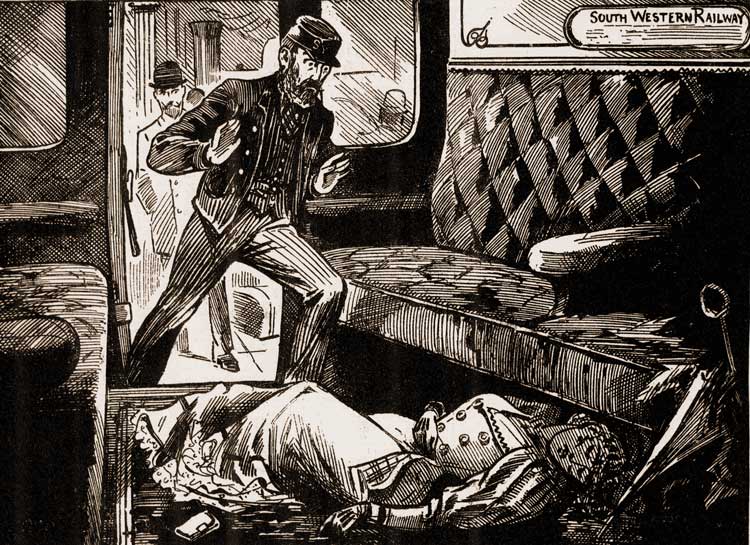

“At an early hour this morning, a rumour was circulated in South London that a shocking crime had been committed in a second-class railway carriage on the London and South-Western Railway.

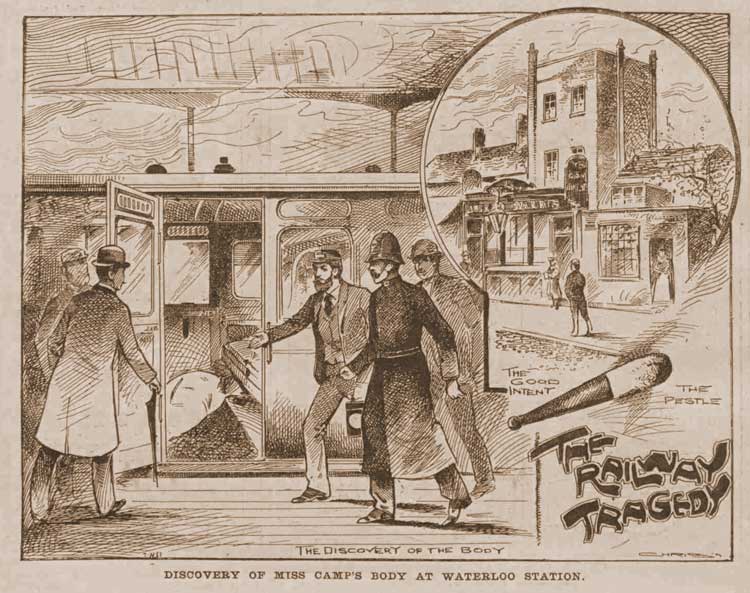

A Correspondent, who inquired at the Kennington-road Police Station, was informed that the body of a well-dressed female had been discovered lying beneath the seat of a second-class carriage in a train, on its arrival at Waterloo Station, with a bullet wound in the head. No weapon was found in the compartment.

The body was placed on an ambulance and removed to the Lambeth parish mortuary to await an inquest.

From further inquiries, it has been ascertained that the murdered woman has been identified as Miss Elizabeth Kemp, barmaid, lately of the Good Intent Tavern, East Street, Walworth.”

HORRIBLE MURDER TRAGIC FATE OF A BARMAID

BODY FOUND IN A TRAIN

ON THE EVE OF MARRIAGE

Later that same day, The South Wales Echo, quoting the Press Association, gave a much fuller account of the circumstances surrounding the crime.:-

“The Press Association states that the-latest information shows that the murder in a railway carriage on the South-Western Railway last night was a crime of a particularly brutal and deliberates character.

The injuries which caused Miss Kemp’s death were evidently caused by some sharp weapon such as a chopper, as the head was very much lacerated and battered. Care was also taken to conceal the body from casual observers by pushing it well under the seat of the carriage.

The body was warm when discovered, but when examined at St. Thomas’s Hospital a few minutes afterwards life was quite extinct.

HER FIANCE IDENTIFIED HER

The first identification of the remains was made by Mr E. Berry, a fruit dealer in Walworth-road, to whom Miss Kemp was engaged to be married within a month.

Miss Kemp had a day off and spent the day at Hammersmith and Hounslow with friends.

Mr Berry went to the station to meet her on her return, and from what he heard he went at once to St. Thomas’s Hospital. There he identified the body, and was naturally much overcome by the spectacle.

The body remains at the Hospital, but will probably be moved to the parish mortuary before the inquest is held.

A POPULAR WOMAN

Miss Kemp, who was about 27 years of age, had been employed as manageress at the Good Intent, East-street, Walworth-road, for some years, and was a general favourite with customers. Prior to going there, she acted as nurse for some time in one of the hospitals in the North of London.

The friends she visited at Hammersmith and Hounslow were sister and brother-in-law, and it was arranged that her affianced should meet the 8.25 train in the evening.

When he was on the platform he saw a commotion, and, hearing what had occurred, he went to the hospital.

No arrests had been made by the police early this morning.

WHERE THE BODY WAS FOUND

The body of Miss Kemp, who was a well-dressed, good-looking young woman, was found packed under the seat of a second-class carriage. There were indications that there had been a desperate struggle in the compartment, the sides of which were besprinkled with blood.

Nothing was found in the compartment with which the injuries could have been inflicted, but a pair of bone sleeve-links was picked up. It has not been ascertained however to whom they belonged.

ADDITIONAL DETAILS

MISS KEMP’S ANTECEDENTS

As the result of further inquiries this morning, the Press Association representative has ascertained that the actual age of Miss Kemp was 30.

It appears that, two years ago, she for some time kept company with another young man, resuming later on the old courtship with Mr Berry. The immediate friends of the deceased are not, however, inclined to believe for a moment that jealousy had anything to do with the tragedy, as they are not aware that she was ever troubled in the least by her old admirer, whose name she was never heard to mention.

After leaving the residence of her brother-in-law (Mr Sheat) at Hammersmith in the afternoon, Miss Kemp proceeded to a general shop at Hounslow kept by another sister (Mrs Haynes). The immediate object of the visit was to assist Mrs Haynes in packing up preparatory to leaving Hounslow, it having been Mrs Haynes’s intention to go to reside with her sister in Walworth within a few days.

The fact that Miss Kemp’s dead body was found in the train by which she intended arriving at Waterloo, appears to conclusively prove that all her original intentions were carried out up to the time of leaving Hounslow.

Nothing was known up to 10.15 this morning regarding the ownership of the sleeve links found in the train.

MR BERRY INTERVIEWED

A representative of the Press Association had an interview early this morning with Miss Kemps lover, Mr Edward Berry, who keeps a fruiterer’s shop in East Street, Walworth, almost immediately opposite the Good Intent public-house, where Miss Kemp had been employed.

Mr Berry was greatly distressed as the result of the terrible tragedy, but he willingly gave all information possible.

A very pathetic fact elicited in the course of the conversation was that Miss Kemp was to have been married to Mr Berry within a month.

She had, he said, been employed at the Good Intent for many years, and her steady behaviour and cheerful nature made her a general favourite in the neighbourhood. “Indeed,” said the grief-stricken fellow, “she was as nice a girl as one could wish to meet.”

She was about 27 years of age, and, as a young girl, she was employed at the Good Intent as a barmaid. After that she for some time acted as a nurse at a hospital at Winchmore Hill, in North London, returning to the public-house in East-street some two years since as manageress on the death of Mr Harris, the landlord.

The last time that Mr Berry saw her he said, was at noon yesterday. It being her half-day off, it was her intention to utilise her leisure in visiting a sister and brother-in-law at Hammersmith and then to proceed to the residence of another sister at Hounslow.

Her lover had arranged to meet her on the arrival of the 8.25 train at Waterloo last night, but of the manner in which she carried out her intentions and of further incidents of the journey, which culminated so tragically Mr Berry, of course, knows nothing. He could only say that Miss Kemp was in a most cheerful mood when she left him, and that in accordance with his arrangement he duly awaited her arrival at Waterloo in the evening.

As she did not put in an appearance at the appointed spot, he at first imagined the train was late.

Several minutes more, however, elapsed, and still she did not appear. He then made inquiries, and found that the Hounslow train had arrived some minutes before. At the same time he became aware of considerable commotion among the police and other railway officials, and, on asking the cause of it, was told that the dead body of a lady had been found in the Hounslow train, and was being conveyed to St. Thomas’s Hospital.

The coincidence of events struck him at once, and, hurrying off to the Hospital, he was horrified to find that his worst suspicions were realised and that the body was indeed that of Miss Kemp. She was quite dead, although the fact that the blood was still warm showed conclusively that the murder was committed not far from Waterloo.

The head of Miss Kemp was in a terribly battered condition. At first, it was thought that she had been shot, but subsequent examination showed that a chopper or an axe had been used to inflict the shocking and fatal injuries.

On being questioned by the reporter as to whether he could suggest any possible motive for the murder, Mr Berry said he was utterly at a loss to account for it. Miss Kemp had not, as far as he was aware, a single enemy, and the deed must have been that of a madman.

Miss Kemp usually carried a good deal of money, but, as Mr Berry was not aware as to what was found upon her, he was not able to say whether or not she had been robbed.

NO CLUE AT PRESENT

The Press Association adds:- Little or nothing can be ascertained from the police, who are naturally reticent as to anything that may have come within their knowledge, and up to half-past-nine this morning the terrible murder still remained a mystery.

It may be taken for granted, however, that neither the railway company nor the police will leave a stone unturned to solve it.

A GRUESOME DISCOVERY

The Press Association learns that the railway line has been searched, and that a chemist’s pestle with blood and hair upon it has been found between Wandsworth and Putney. It is believed, however, that Miss Kemp’s injuries were caused by some heavier weapon.

The presumption is that the murder was committed between Wandsworth and Putney.

MISS KEMP’S SISTER’S NARRATIVE

A representative of the Press Association has had an interview at Hounslow with Mrs Haynes, sister of Miss Kemp.

Mrs Haynes, who was in a very distressed condition and hardly able to realise the sad fate which had overtaken her sister, said the deceased reached her house about 5 o’clock yesterday afternoon and seemed in the best of spirits up to the time of her departure.

Mrs Haynes cannot form any idea as to a motive for the crime. The motive if any was, she felt sure, not robbery, for her sister’s brooch, earrings, and silver-mounted umbrella were found on the body.

Mrs Haynes saw her sister off at Hounslow. She put her into a second-class carriage, in which there was no other occupant, and inclines to the idea that someone entered later on and made an attempt to criminally assault her sister. Then in the struggle or to cover his escape he murdered her.

Mrs Haynes added that she practically knew nothing of the matter, and that the police were reticent even to herself.

She said, however, that she did not believe that the bone links found in the railway carriage were her sister’s as the deceased was accustomed to wear gold links, and she (Mrs Haynes) did not notice any bone links yesterday.

The deceased made some purchases at Hounslow yesterday, and remarked that she had spent nearly all her money.”

THE INQUEST OPENS

The Reading Mercury, in its edition of Saturday, 20th February, 1897, carried the news that the inquest had opened on the previous Tuesday, and also revealed that the murder had caused terror amongst women who travelled on the line:-

“On Tuesday, Mr. Braxton Hicks opened the inquest on the body of Elizabeth Camp, who was murdered in a train on the South-Western Railway on Thursday in last week.

Mrs Annie Sheat, of Hammersmith, having identified the remains as those of her sister, the coroner adjourned the inquiry for a month to enable the police to continue their investigations.

Many clues have been followed up, and all upon whom it was possible suspicion could fall have been traced and questioned.

A medical examination the body has confirmed the suspicion that the fatal injuries were inflicted by the pestle found on the line.

A marine store dealer has come forward and stated that he sold a pestle to a man similar to one who was several times noticed in the public-house at Walworth, where the murdered woman was employed.

The murder has caused a widespread alarm amongst women travelling upon the line, and a woman, travelling in a compartment alone with a man, was nearly thrown into a fit because the man opened his knife before her in order to trim broken nail.”

THE RAILWAY MURDER

Meanwhile, many newspapers were pointing out that the murder highlighted the danger posed to passengers, especially to women travelling alone, of the box-carriage system adopted by the railway companies.

The Exmouth Journal was just one paper that raised the issue on Saturday, 20th February, 1897:-

London and all Britain, indeed, have been once more startled and shocked by the matter of the terrible outrage on the London and South-Western – in which a young woman named Camp, a barmaid who was about to be married, was foully murdered – by a railway tragedy of peculiarly atrocious character, and one which, apart from the horror of its details generally, is calculated specially to alarm the travelling public.

Here was a young woman riding through a busy suburban district, with the train which conveyed her making stoppages every four or five minutes, foully murdered by some miscrant who was enabled to escape and leave scarcely a clue behind him.

Not only was the victim fiercely despatched, but her body was hidden away under a seat unnoticed until a servant of the company entered the carriage when the passengers had departed. It is a commentary upon the insecurity of our everyday railway travelling, which seems to call for immediate attention.

THE DANGERS OF BOX CARRIAGES

The papers are full of the details of the hunt for the murderer, but, meanwhile, we may here reproduce a letter in connection with the crime from “an indignant British matron,” who asks:- “Will anything be done now to sweep away our box-like railway carriages? Or is this latest crime merely to go by as a sorry accident?

Is it not a burning disgrace that we encourage these evils by presenting to evildoers opportunities that cannot fail to allure them? What safety is there for women or even men if boxed up with a stranger and travelling alone?

No one is responsible. No railway company guarantees the safety of its passengers. They are left entirely to themselves. The guard is boxed up in his little corner and other people are boxed up in their little corners. Well, if anything happens, a shrug of the shoulders seem to say, “if folks travel what can they expect?”

THE BENEFITS OF CORRIDORS

Travel we must, and at the end of the nineteenth century is it too much to expect the means for doing so with decent safety?

It will probably take our addled conservative minds another century to grasp the benefits that will accrue from having corridor trains all over our country.

Nothing could be more simple than those resembling the tramcars, and, even if the cars should be very scantily peopled, could not the guard of the train occasionally walk through from one end of the train to the other?

It is no wild dream at all, nor is it an idea borrowed in advance from the joys and comforts of the coming millennium. It wants a little common sense to promote it, and the result will be satisfactory.

As it is, we must put up with what we have got, ride third-class whenever we are unescorted, and eschew the rapidity of railway travelling whenever possible.

Crimes may well flourish when so carefully nurtured and encouraged by the combined wisdom of the 19th-century railway company.”

FEWER AND NICER PEOPLE

“One little incident of the tragedy is that the deceased’s sister once asked Miss Camp why she travelled second-class. “Oh! there are fewer and nicer people.” “Ah”, said her sister, laughingly, “the third-class carriage affords better protection to a woman.”

THE COMMISSIONER’S REPORT 1898

As it transpired, the murder of Elizabeth Camp was, like the Jack the Ripper murders, destined to remain unsolved. albeit the police did have several suspects, and one in particular who, but for a delay in the case being reported to the Metropolitan Police, may well have been charged and prosecuted as the perpetrator of the crime.

In November, 1898, Sir Edward Bradford, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, published his report for 1897, and made specific mention of the fact that his force had not been informed of the murder until it was too late, and the delay meant that a promising suspect was, in consequence, able to evade justice.

The London Evening Standard published the Commissioner’s criticism on Saturday, 29th November, 1898:-

Regarding the crime on the London and South-Western Railway, Sir E. Bradford remarks:- In the case of Elizabeth Camp, found murdered in a London South-Western Railway carriage at Waterloo on the 11th of February, the body was removed from the Railway Station to St. Thomas’s Hospital, and from thence, after a medical inspection, it was sent to the mortuary, the police remaining in ignorance that any crime had been committed.

During the time that thus elapsed, the murderer was drinking in a certain public-house, but the opportunity of taking him red-handed was lost, and evidence was afterwards lacking to justify an arrest.”

Elsewhere in the same issue, the Standard commented in an editorial on the report that:-

“The case of Elizabeth Camp gives rise to something like a complaint against the hospital authorities for not furnishing information to the police that a crime had been committed, the murder in the meantime enjoying himself at a public house.

How far hospital authorities might be rightly expected to assist the police seems to be a moot point, as indicated by some other cases as well as this.”

THE HOSPITAL’S RESPONSE

However, St Thomas’s Hospital considered the criticism to be both unfair and untrue, and, on the 1st of December, 1898, the newspaper published a letter from St Thomas’s Treasurer, Mr J. G. Wainright, in which he refuted the Commissioner’s accusation:-

“As this is the Hospital referred to, may I be allowed to point out that the woman was brought here by a London and South-Western Railway policeman at a quarter to nine on the evening of February 11th, 1897, and, on her being found to be dead, a police-constable of the L Division was at once summoned, who conveyed the body to the Lambeth Mortuary at a quarter-past nine pm?

It will thus be seen that, in spite of the fact that the body was brought here by one of the London and South-Western Railway police force, we gave immediate information to the Metropolitan Police, when our responsibility ceased.”

I am, Sir,

your obedient servant,

J. G. WAINWRIGHT, Treasurer.

Albert Embankment, London. S.E.,

November 30.

SIR ROBERT ANDERSON RECALLS THE CASE

In September, 1908 Sir Robert Anderson, who was head of the Criminal Investigation Department during the Whitechapel Murders and beyond, looked back on the murder of Elizabeth Camp and lamented the fact that it demonstrated how, compared to the French system, the English system had been found wanting.

The Bolton Evening News reported his musings on Wednesday 2nd September, 1908:-

“Sir Robert Anderson contrasts the English and French police powers.

In France, the place where a murder is committed is immediately closed, if possible, to the public, and nothing is allowed to be touched till the Chief and his staff have completed their inspection and inquiries. If any clue be left, it is there undisturbed for the police to see.

The larger spirit of freedom and curiosity in England are not over-concerned about police functions as the first thought.

UNAWARE OF THE CRIME

Sir Robert Anderson recalls the South-Western Railway tragedy, and says that Miss Camp had been taken St. Thomas’s Hospital before Scotland Yard were aware of the crime, news of which only reached the authorities through an officer seeing the victim being conveyed through the streets from Waterloo to the Hospital.

The custom in France would have sealed the doors of the carriage, which would have been removed to a siding, or into a shed, placed in charge of officials, and the police called for to examine the undisturbed body and compartment.

It cannot be asserted with truth that in England the police are not, in the vast majority of cases, summoned at the earliest moment, nor can it be said that they lack public help. But it is possible that French ideas and practice might be useful in some instances in England…”