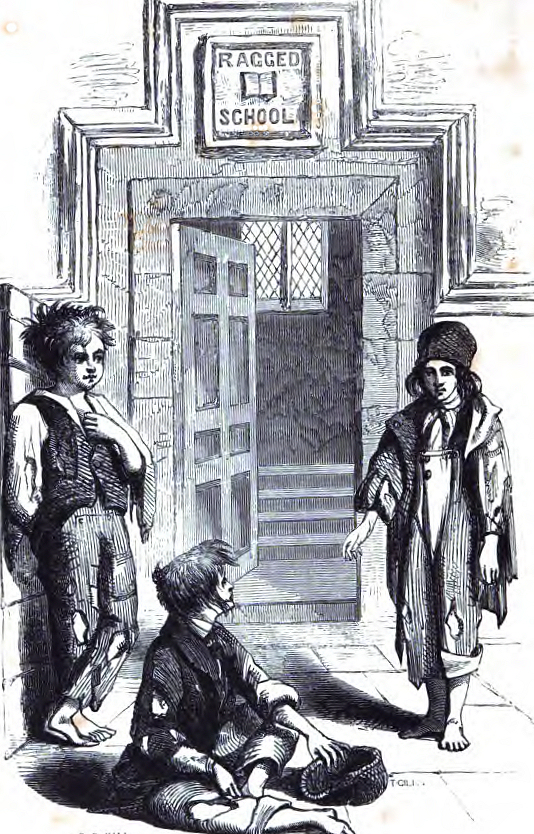

One of the many intriguing places to visit on a trip to the East End is the Ragged School Museum, which is situated at 46-50 Copperfield Road, London, E3.

The museum itself occupies a group of three canal-side buildings, and the complex once had the distinction of being the largest “ragged” – or free – school in London.

It was founded by the redoubtable Dr. Thomas Barnardo in the late 1870’s and, by the time of its closure in 1908, tens of thousands of East End children had passed through its doors to receive a rudimentary education.

JUST ONE OF MANY RAGGED SCHOOLS

But, this was just one of many such schools that were established throughout the 19th century in the working-class districts of the large industrial towns of Britain, where an immense poverty-stricken, and uneducated underclass had been allowed to develop, mostly unchecked and, largely, uncared for by the authorities.

EAST END POVERTY

Nowhere was this more apparent, nor more widespread, than in the East End of London, where the growth in population resultant from the Industrial Revolution had seen a huge growth in population which, in turn, had led to people being forced into overcrowded, unsanitary housing.

Unemployment was rife and poverty was everywhere. Diseases, such as cholera, often struck down the breadwinner of a family leaving their children, should they survive, destitute and forced to survive as best they could on the streets, sleeping in wherever they could find a berth, be it in an abandoned loft or a cold wet and damp railway tunnel.

300,000 DESTITUTE CHILDREN

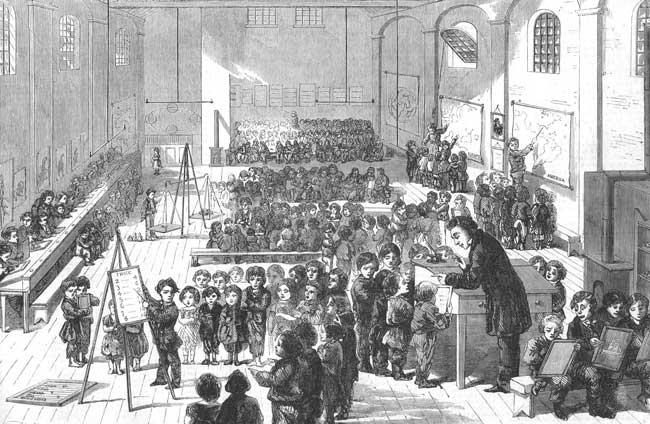

Indeed, something of the squalor that vast swathes of Victorian society were forced by necessity to exist in can be gleaned from the stark statistic that, in London alone, between 1844 – when the Ragged Schools Union was established – and 1870 – when Parliament passed The Elementary Education Act, which set a framework for the schooling of all children between the ages of 5 and 13 in England and Wales – some 300,000 children had been educated and cared for by the dedicated ragged school teachers, the majority of whom were themselves drawn from the working classes of the period.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN LIFE AND DEATH

The “cared for” element was hugely important because, these institutions weren’t just about educating their pupils, but they also provided food, clothing, lodging and other home missionary services for them.

So, the good that they did, and the benefits they provided, extended far beyond improving the minds of the children of the East End. Indeed, there must have been many occasions when the schools made the difference between life and death for the waifs, strays and forgotten underdogs of Victorian society.

THE ORIGINS OF THE RAGGED SCHOOLS

But where did it all begin?

Although the Ragged School Union was formed in 1844, charitable schools were, sadly, already thriving in many parts of the country.

THE TEACHING TAILOR

In 1798 Thomas Cranfield, a tailor by trade, had established a free day school for children on Kent Street, near to London Bridge.

Such was his devotion to administering to the needs of the poor London children of the period that, by the time of his death in 1838, the seemingly inexhaustible Cranfield, had established a grand total of 19 such establishments for the schooling of poor children in the more poverty-stricken districts of London.

THE CRIPPLED COBBLER

In Portsmouth in 1818, cobbler John Pounds – known as the “crippled cobbler” on account of a debilitating fall he had taken into a dry dock when he was twelve years old – began offering free schooling to the poor children of Portsmouth.

He would roam the streets and quays in search of pupils, often carrying pockets filed with hot potatoes with which he would bribe them to come to lessons.

THE LONDON CITY MISSION

The term Ragged School, however, was not generally used in reference to these establishments until the 1830’s.

In 1835, a young Scotsman by the name of David Nasmith (1799 – 1840) founded the London City Mission in Hoxton East London. Its missionaries went out amongst the poor and destitute of London and ministered to both their physical and spiritual well being.

Something of the immense task that confronted then can be gleaned from a report by one of the early missionaries who wrote that, “Last year I walked 3,000 miles on London pavements, paid 1,300 visits, 300 of which were to sick and dying cab men.”

Their dedication is further highlighted in the minutes of their Annual General Meeting, which took place on Tuesday 15th May 1838, in which it was reported that, “…during the present year the agents of the mission have paid 205, 917 visits to the poor, 23,771 of which were to the sick and dying.”

A SHORT VIDEO ON THE MISSION’S HISTORY

THE FIRST RAGGED SCHOOL

It was one of their missionaries, Andrew Walker, who established what is generally acknowledged to be the first Ragged School, which he set up in 1835 in a disused stable in Westminster, with financial backing from Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury (1801 – 1885).

The Mission’s fifth annual report of 1840 made specific mention of the establishment in the previous year of five schools “formed exclusively for children raggedly clothed,” which were being attended by a total of 570 children. These children, seldom wore shoes and were, therefore, unsuitably attired to attend any other type of school.

THE RAGGED SCHOOL UNION

The term “raggedly clothed”, and the concept of establishing places of learning for the neglected offspring of the poor, quickly caught on and, by 1844, around 20 “Ragged” schools had been set up and it was rapidly becoming clear that they would all benefit from being governed by a central body that could promote their cause and service their work.

Thus, in April 1844 The Ragged School Union was formed, with The Earl of Shaftesbury as its President – a position he held, and dedicated himself to, for the next forty years. He was an inspired choice as leader since, as one commentator has put it, “he gave what had been a Nonconformist undertaking the cachet of his Tory churchmanship.”

Thanks to his patronage and the support of newspapers the Ragged School movement saw a massive growth in the numbers of schools, teachers and students.

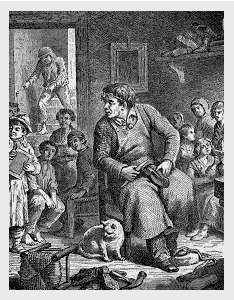

Many of those who ran the schools were drawn from the lower echelons of Society.

A RAGGED SCHOOL AT WINDSOR

In 1846 the Reverend Robert Ainslie, preparing for an upcoming lecture, paid a visit to a Ragged School in Windsor and was most impressed by what he discovered:-

“There were upwards of a 100 young person present from the ages of 18 to 10, boys and girls all behaving with the greatest decorum and respectability, tolerably well clothed…they were in a shed, not boarded, the floor of earth, with a fireplace to keep them warm and comfortable..”

The pupils, so he continued, were able to read and were able to answer questions, which “…but a few weeks ago might just as well have been put to the very boards upon which they were sitting.”

“And who had done all this?”, he asked, before declaring his admiration for the individual responsible in his answer:-

“Not the Court ! Not the Peers! Not the Clergy! Not the Dissenting Ministers! Not the wealthy inhabitants of the neighbourhood! No, it had been done by a poor and humble chimney sweep; who had himself been a bad and abandoned man, but who was reclaimed, and who now sat there, with his dirty face, teaching and doing more good than thousands of others of ten times his capacity…”

EDUCATION RATHER THAN INCARCERATION

On the evening of Tuesday the 3rd of February 1846, the aforementioned Reverend Robert Ainslie gave his lecture about the Ragged Schools at the Literary and Scientific Institution, on Aldersgate Street.

He began by declaring that he “appeared before the audience in the character of an advocate for the juvenile portion of the poorer population, for the purpose of urging upon their attention the necessity of judicious measures being adopted for the improvement and education of children born into the world under circumstances of a most unfavourable nature, born in the midst of more want, distress, infamy and crime, than it was possible to conceive in an intelligent and free county.”

It seemed to him that “the present state of the public mind and of public morality was very advantageous for the improvement of the community. Something of improvement was now being attempted in the shape of free schools, known its the ragged schools for children.”

The origin of the name was, he said, “the fact that the clothes of the children were all in a ragged condition; where one was ragged the others were ragged also.”

He then went on to make a point that was being made more and more by those members of Victorian society who were advocating education for all. The point was that the authorities were busily spending vast amounts of money to build prisons in which to incarcerate offenders, whereas a smaller amount spent on educating people would tackle, and possibly eradicate, the very conditions that had led those offenders into a life of crime in the first place.

As an example, he cited the county of Essex which, he said, had recently spent almost £35,000 building a large county prison. “How much better would it not be,” he observed, “to have spent that sum in educating the poor rather than in building a prison for punishing them?”

His message garnered a great deal of support, not least from Charles Dickens who, the next day, wrote a letter of support to the Daily News.

CHARLES DICKENS VISIT TO A RAGGED SCHOOL

In 1841 a Ragged School had been established in Field Lane, off Saffron Hill in London.

In 1843, Charles Dickens had paid it a visit at the behest of Angela Burdett-Coutts (184-1906), who wanted to know if she should invest money in the movement. Dickens, who was already familiar with the vicinity, as he had used it as the location for Fagin’s lair in Oliver Twist, dutifully paid the school a visit. He was impressed by the dedication shown by the teacher but, at the same time, appalled by the condition of the children that he met.

DICKENS LETTER ABOUT HIS EXPERIENCE

On the 4th February 1846, in response to Robert Ainslie’s lecture, he wrote to the Daily News and recalled the conditions he had encountered:-

“…It consisted at that time of either two or three – I forget which-miserable rooms, upstairs in a miserable house. In the best of these, the pupils in the female school were being taught to read and write; and though there were among the number, many wretched creatures steeped in degradation to the lips, they were tolerably quiet, and listened with apparent earnestness and patience to their instructors. The appearance of this room was sad and melancholy, of course – how could it be otherwise! – but, on the whole, encouraging.

The close, low chamber at the back, in which the boys were crowded, was so foul and stifling as to be, at first, almost insupportable. But its moral aspect was so far worse than its physical, that this was soon forgotten. Huddled together on a bench about the room, and shown out by some flaring candles stuck against the walls, were a crowd of boys, varying from mere infants to young men; sellers of fruit, herbs, lucifer-matches, flints; sleepers under the dry arches of bridges; young thieves and beggars–with nothing natural to youth about them: with nothing frank, ingenuous, or pleasant in their faces; low-browed, vicious, cunning, wicked; abandoned of all help but this; speeding downward to destruction; and UNUTTERABLY IGNORANT.

This, Reader, was one room as full as it could hold; but these were only grains in sample of a Multitude that are perpetually sifting through these schools; in sample of a Multitude who had within them once, and perhaps have now, the elements of men as good as you or I, and maybe infinitely better; in sample of a Multitude among whose doomed and sinful ranks (oh, think of this, and think of them!) the child of any man upon this earth, however lofty his degree, must, as by Destiny and Fate, be found, if, at its birth, it were consigned to such an infancy and nurture, as these fallen creatures had!

This was the Class I saw at the Ragged School. They could not be trusted with books; they could only be instructed orally; they were difficult of reduction to anything like attention, obedience, or decent behaviour; their benighted ignorance in reference to the Deity, or to any social duty (how could they guess at any social duty, being so discarded by all social teachers but the gaoler and the hangman!) was terrible to see. Yet, even here, and among these, something had been done already. The Ragged School was of recent date and very poor; but he had inculcated some association with the name of the Almighty, which was not an oath, and had taught them to look forward in a hymn (they sang it) to another life, which would correct the miseries and woes of this.

The new exposition I found in this Ragged School, of the frightful neglect by the State of those whom it punishes so constantly, and whom it might, as easily and less expensively, instruct and save; together with the sight I had seen there, in the heart of London; haunted me, and finally impelled me to an endeavour to bring these Institutions under the notice of the Government; with some faint hope that the vastness of the question would supersede the Theology of the schools, and that the Bench of Bishops might adjust the latter question, after some small grant had been conceded. I made the attempt; and have heard no more of the subject from that hour…”

INSPIRATION FOR A CHRISTMAS CAROL

Indeed, it was the children he encountered on the visit to the Field Lane Ragged School that inspired the memorable scene in A Christmas Carol – written in 1843 – when, in Stave Three, Scrooge notices “something strange” protruding from the skirts of the Ghost of Christmas Present.

“Is it a foot or a claw”, Scrooge enquires, only to have the spirit bring from the foldings of its robe two “…wretched, abject, frightful, hideous, miserable..” children, whom Dickens describes as:-

“Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing. No change, no degradation, no perversion of humanity, in any grade, through all the mysteries of wonderful creation, has monsters half so horrible and dread.”

Appalled by the very sight of them, Scrooge recoils in horror, whereupon the spirit admonishes him with the dire warning:-

“This boy is Ignorance. This girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy, for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.”

THE DECLINE OF THE RAGGED SCHOOLS

Following the passing of the Elementary Education Act in 1870, the number of Ragged Schools began to diminish dramatically and the Union itself came to be seen as somewhat archaic by many of the new breed of educators, as the newly established School Boards took over the role of educating all classes of society and were obliged to provide elementary education for children aged 5–13 (inclusive). Whereas, officially, parents were meant to pay for their offspring’s education, the Boards would pay the fees of children whose parents were too poor to do so.

Although it would be many more years before the educational system that we tend to take so much for granted today came into being, the 1870’s saw the start of that journey, and it could be argued that the Ragged Schools had, at least, paved the way for many of the later schools – such as the Board and Church Schools – to continue the work that they had begun.

It is also worth acknowledging, however, the fact that many who would become instrumental in the development of the later education system, such as Quintin Hogg (the founder of the Regent Street Polytechnic) and even Dr Thomas Barnardo, had themselves worked in and gained experience in the Ragged Schools.

And, what cannot be denied, is the fact that the Ragged Schools movement had, most certainly, proved to be a significant feature in the lives of many underprivileged children and young people in the 19th century and, doubtless, there were those who enjoyed a better life than they would have done without them.