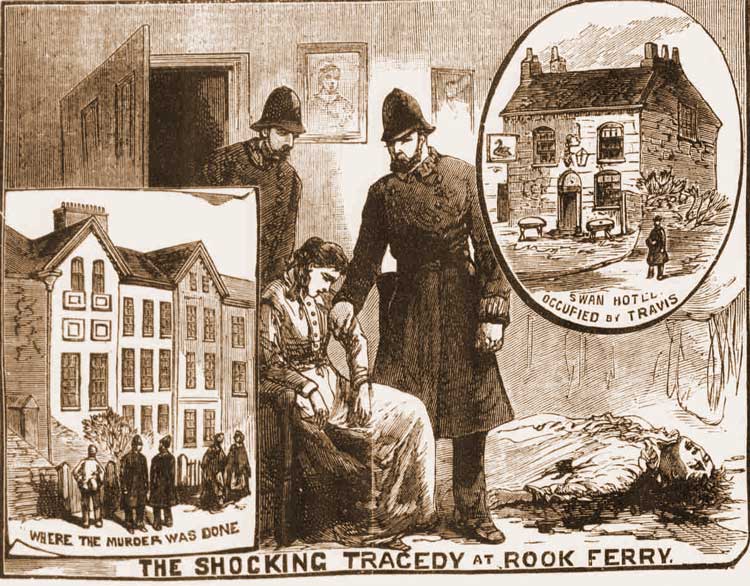

At around 2 am, on Saturday, 13th February, 1886, John Dickinson, who lived at 14, Mersey Road, Birkenhead, heard screams of “Murder!” coming from the house of his next-door neighbours’ Captain M’Intyre and his wife, Jane.

The Captain himself was away in Cardiff, and twenty-six-year-old Jane, so far as Mr Dickison was aware, was alone in the house, with only the couples pet Retriever for company.

Mr. Dickinson immediately sent for the police, and soon Inspector Asbury and Police Constable Dean had arrived at the house.

They discovered that the gate to the backyard of the M’Intyres’ house was open, and, passing into the yard, they found a man lying unconscious on the flagstones. The bedroom window directly above them was open, and it was evident to the police officers that the man had jumped from the window, injuring himself in the process.

FOUND UNCONSCIOUS IN BEDROOM

Suspecting foul play, the two men sealed all the doors, procured a ladder, and climbed up it to enter the house through the open bedroom window.

The room being in darkness, they could see nothing at first. But, on lighting the gas lamp, they were horrified to see the body of Jane M’Intyre lying stretched out on the floor in front of the fireplace, her feet resting on two pillows. Her body was covered in blood, her head was terribly bruised, as was the rest of her body, and it was evident to the two policemen that she had had been “savagely beaten” with a blunt instrument.

She was, at that point, still alive, so Inspector Asbury sent for a doctor, but Mrs M’intyre died shortly after the medic’s arrival, having been unable to tell the police officers what had happened.

THE WOMAN ON THE CHAIR

Sitting on a chair close by, they discovered Jane M’Intyre’s sister, Eliza Platt, who, so they later recalled, seemed to be “in a stupid state, evidently from drink.”

A further search of the bloodstained room uncovered the murder weapon, a pair of brass tongs, which lay twisted a broken on the floor near the fireplace.

Elsewhere in the room were found a man’s hat and coat.

It was evident to the two officers that the man who was lying insensible in the yard, having carried out the murder, had attempted to escape from the scene of the crime by jumping through the bedroom window, tearing down the Venetian blinds and breaking two panes of glass in the process, but had been knocked unconscious on hitting the yard thirty feet below.

THE MAN REGAINS CONSCIOUSNESS

Fifteen minutes later, the man had regained consciousness and was escorted into the kitchen of the house, where he was identified as Robert Travis, the landlord of the Swan Hotel in Great Sutton.

On searching him, the police noted blood-spatters on his clothing and they also found six sovereigns concealed in his pocket and an additional four in his stockings.

Robert Travis and Eliza Platt were charged with the murder of Jane M’Intyre and were taken to the Tranmere Bridewell.

It later transpired that the two of them, Platt and Travis, were due to be married the following week.

The two of them appeared at Birkenhead Police Court on that Saturday morning where they were remanded in custody for a further week.

AN IMPORTANT STATEMENT BY MISS PLATT

On Wednesday 17th February, 1886, at the inquest into Mrs. M’Intyre’s death, a statement was read out from Eliza Platt, which cast doubt on her having been involved in the actual murder of her sister.

The South Wales Echo published the statement in full in its edition of Thursday, 18th February, 1888:-

“My aunt (Mrs Maddocks) received a letter on Wednesday evening from my brother-in-law, Captain M’Intyre, and she (my aunt) requested me to go down to Rock Ferry to see them.

I went, and when I arrived there I found my sister in bed, and a charwoman named Mrs Houghton and her husband sitting at the kitchen fire. I went upstairs, and asked my sister if she had had a doctor, and she said no. I said “You had better send for a doctor,” and she replied, “it is too late tonight; I will send for one tomorrow.”

Mrs Houghton and her husband went home, and I locked up the house and went to bed.

On the following day, I sent for Dr Nickson, and he prescribed for my sister, but she would not let me send for the medicine. After the doctor had been to the house the next day I sent for the medicine, and my sister took one dose.

TRAVIS VISITED THE HOUSE

Between one and two o’clock in the afternoon, the prisoner Travis came and asked how Mrs M’Ityre was. I went upstairs and told her, and she asked me to have him up. I took him upstairs, and we remained about an hour in the bedroom. He then said he was going to Liverpool, and said that he would call on the way back.

He returned to the house about six o’clock, and I went upstairs and told my sister that he had called again. She told me to call him up. I did, and my sister asked him to have some tea, but he said that he had had tea in Liverpool. He brought a bottle of whisky with him, and it was opened, and some poured out into three glasses, which each of them drank. We sat there talking for about an hour, and my sister wanted some oranges. I sent the girl out for threepenny-worth.

We sat for some time afterwards, when my sister asked for a little more whisky, which I gave her. I think it would be near nine o’clock then and Mr Crispin called. I played a few tunes on the piano, and Mr Crispin left when it was near ten o’clock.

My sister asked me to play again, and I played till it was pretty near eleven o’clock. I then went into -my sister’s bedroom, and sat awhile, after which I asked Travis to go, as we had no beds made up in the house.

HE FLEW INTO A RAGE

He said that he would sleep on the sofa. I pressed him again to go, when he flew in a rage, and struck me twice in the face. The second blow knocked me down, and caused my nose to bleed profusely. That was in my sister’s bedroom, by the fire-place.

My sister remonstrated with him about it, and he calmed down. He afterwards went out of the bedroom for the purpose of lying on the sofa. My sister said I was to let the fire go out, as the room was too warm. I sat by the fire while it was dying out and fell asleep.

A SCUFFLING IN THE ROOM

I don’t know exactly how long I slept for, when I was awoke with a scuffling in the room.

I had left the gas burning, but when I was awakened the room was in darkness. The scuffling went on, and I called out “Jane, Jane, what is the matter?” I received no answer. I got up to look for the matches to light the gas, and when I was going round I was struck a blow on the left shoulder with something heavy. My sister screamed out “Oh, Lord Oh, dear.”

The blow caused me to sink down into a chair.

My sister staggered to where I was sitting, and fell upon me. She remained on me for a few minutes, and then slipped down helplessly on the floor. I then heard something fall in the room, followed by a smash of glass, and someone jumped through the window.

That is all I remember till the police came.

That is all I have to say. I felt wet on my hands, but I could not see what it was, for the room was in darkness.”

Having heard the inquest evidence, the jury returned a verdict of “guilty of wilful murder” against Robert Travis, but the jurors chose to believe Miss Platt’s statement and they exonerated her of having any involvement in her sister’s murder.

TRAVIS AND PLATT IN COURT

However, as far as the police were concerned, she was still a suspect in her sister’s murder, and she and Travis were kept in custody, pending a further court appearance.

Prior to their next court appearance, Robert Travis claimed that he had actually been asleep on the sofa when he had been awakened by screams coming from Jane M’Inture’s bedroom. Entering the room, he had found it to be in total darkness. As he entered, he had been struck by several blows, and he had jumped out of the window to escape his assailant.

At the subsequent court appearance, the two prisoners were committed to stand trial for the murder of Jane M’Inytyre.

Their trial took place at Chester Assizes on Wednesday, 12th May, 1886, and, almost immediately Mr. Higgins, on opening for the prosecution, requested that Eliza Platt be discharged, as the case against her was not conclusive, and she could then be called as a witness for the prosecution. The Judge, Mr. Justice Hawkins, concurred, and he duly instructed the jury to return a verdict of not guilty in her case.

ROBERT TRAVIS FOUND GUILTY

The case against Robert Travis was then proceeded with, and evidence was heard which suggested that Travis had carried out the murder in a frenzied, drink-induced rage. Indeed, Eliza Platt testified that, as they were standing in the dock, Travis had said to her, “I don’t know what will become of me; it was all the whisky that caused me to do it.” She also emphatically denied being engaged to marry Travis.

Following a three-hour-summing up by the judge, the jury returned a verdict of “Guilty”, but they recommended mercy on the grounds that, “the act was a frenzied one and was unpremeditated.”

Mr, Justice Hawkins, however, stated that the case was another “sad illustration of the misery and wretchedness produced by indulgence in drink”, and he donned the black cap and sentenced Robert Travis to death.

A HUGE AMOUNT OF PUBLIC SYMPATHY

As Robert Travis languished in prison, a huge groundswell of public sympathy for him began to gather momentum, and more than 14,000 people signed a petition to the Home Secretary, Sir Henry Matthews, requesting him to intervene and commute the deaths sentence to one of life in prison.

In addition, as reported in The Cheshire Observer, on Saturday, 29th May, 1886, several people had come forward to contradict the statements made by Eliza Platt at the trail:-

“With reference to the statement made by Elisabeth Platt that while she and Travis were in the dock at the Birkenhead Police Court Travis said to her, “I don’t know what will become of me it was all the whisky that caused me to do it,” affidavits have been made by Inspector Parker and Constable Shearwood, who were in charge of the prisoners, to the effect that from the time they received them into custody until they were finally committed for trial they took the greatest precaution to prevent communication of any kind passing between the prisoners, and that they both were in such a position that, even if those words had been whispered by Travis to Platt, they must have heard them.

Superintendent Clarke has also made an affidavit, in which he states that when the prisoners entered the dock they were placed in such positions by Inspector Parker and Constable Shearwood that the prisoners could hold no conversation with each other, either by sign, token, or otherwise, without Parker and Shearwood both hearing and seeing.

In reference to Platt’s denial at the trial that she was engaged to Travis, a letter has been forwarded to the Home Secretary, signed by Travis, which is said to be in the handwriting of Miss Platt. This letter is addressed to the registrar of marriages at Great Sutton.”

A REPRIEVE GRANTED

That same day, Saturday, 29th May, 1886, just before noon, a telegram was sent from the Home Office to Mr. R. B. Moore, Travis’s solicitor, containing the following good news:-

“Whitehall, 28th May, 1886

Sir,

With reference to the numerous memorials forwarded by you on behalf of the prisoner Robert Travis, I am directed by the Secretary of State to acquaint you that after having fully considered all the circumstances of this case, he has felt justified in advising her Majesty to commute the capital sentence to one of penal servitude for life.

I am &c.

Godfrey Lushington.”

NEWS BROKEN TO TRAVIS

The Cheshire Observer published the following account of the prisoner’s reaction to the reprieve, in its edition of Saturday, 5th June, 1886:-

“Intelligence from Knutsford states that when Captain Price, the governor, received the commutation of the sentence of death passed upon Travis, he, in company with the chaplain, the Rev W. Truss, went at once to the condemned cell and communicated the intelligence to Travis, whose whole concern has been for his family.

He expressed himself delighted, but declared himself not guilty of the crime, which he has sturdily done ever since he stood in the dock, when his parting words were a declaration of innocence.

Captain Price expects to receive an order for the convict’s removal to Stafford Gaol in about a month, and from there he will be consigned to a convict establishment to work out his terrible sentence.

Mrs Douglas, Travis’s daughter, was present st Knutsford when the Home Office reprieve arrived.

Travis will now be able to see his relatives once only before his departure.”

RELEASED FROM PRISON

Two years later, in June, 1888, Lords Bramwell and Esher, undertook a review of the case and concluded that Travis’s conviction was, in fact, unsafe, and his 1886 conviction was overturned and he was duly released from prison.

A representative from The Liverpool Daily Post promptly caught up[ with him, and the following interview with the newly released man appeared on Saturday, 16th June, 1888:-

FREE AT LAST

“…Travis does not himself Know why he was released.

“Did they give you any reason?” asked the interviewer.

“No, not they. They simply marched me off to the baths, and when I had bathed my own clothes were given to me. Then I knew it was all right. “Thank God”, I said myself, for I darn’t even thank Him above my breath, “free at last.”

Then the doctor came round. “What’s wrong, Travis?”, he said. “I’m going home, sir.” “Home? A lifer going home? Well, I never heard of such thing before.'”

And then I was marched to the big gates, and they were opened wide; wide as they were, they were barely wide enough, I thought, for a free man. They gave me a ticket and a bit of money in my pocket, but I didn’t think of money. If it had been half-a-crown or a thousand pounds it would have been just the same. I was free; that was all I knew, and it was all I wanted to know.

They took my address in Liverpool here, and when I got into Lime Street Station, at about a quarter to nine on Saturday night, I quite expected somebody would have been there to meet me, thinking the authorities had telegraphed to them, but there were nobody there. So I went to my friend’s near here, and sent word up to my son-in-law, and he came to me.”

AN APPLICATION FOR COMPENSATION

Travis had been all but financially ruined by his experience, and his health had deteriorated. Thus, in December, 1888, his supporters launched a campaign to get him some official compensation for his wrongful conviction.

Sir Henry Matthews, however, on reviewing all the facts of the case, refused to grant him any compensation.