Throughout the closing weeks of November 1888 it was becoming apparent to many observers that the police investigation into the Jack the Ripper murders was in total disarray. With the resignation of the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Charles Warren, and a total lack of progress in hunting down the perpetrator of the crimes, many newspapers were questioning the capabilities of the force tasked with keeping Londoners safe, whilst ore than one paper was asking the simple question – where are the police?

ANOTHER ATTACK ON A WOMAN

On Sunday 25th November 1888, Reynolds Newspaper carried a report concerning an attack on a woman that had recently occurred at one of the Common Lodging Houses in George Street, Whitechapel. Pointing our that the attack had, in fact, taken place “close to to the scene of the last murder” – a reference to the murder of Mary Kelly, which had taken place in Miller’s Court, off Dorset Street, on 9th November 1888, the article went on to give some specifics of this latest atrocity which had, apparently, occurred on Wednesday 21st November.

“London was subjected on Wednesday last to one of those recurring fits of horror that have given the East-end such unhappy notoriety. An unfortunate woman living in a Common Lodging House in George Street…had a wrangle with a man with whom she had spent the night, in the course of which a slight wound was inflicted on her throat by a blunt instrument… ”

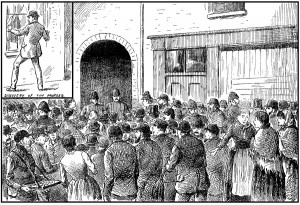

Within moments of the attack, the alarm had been raised and the belief that it had been another attack in the Whitechapel murders sequence led to a massive hue and cry that brought men and women alike out onto the streets where they pursued the attacker through the labyrinth of alleyways and passageways that snaked their way through the district.

However, they had failed to catch him and the assailant has escaped – a fact which, so Reynolds Newspaper informed its readers, “seems to prove that the pursuit was anything but ardent.”

The whole affair, so the report continued, “amounted to little more than one of the usual brawls that occur every week between drunken and dissolute men and women in the hives of vice that abound in every quarter of the East-end.”

OF LITTLE IMPORTANCE

Whilst opining that the event itself was “of little importance” since, as the feature writer observed, “brawls ending in the drawing of blood are the commonest product of society in all communities where wealth abounds side by side with abject poverty…”

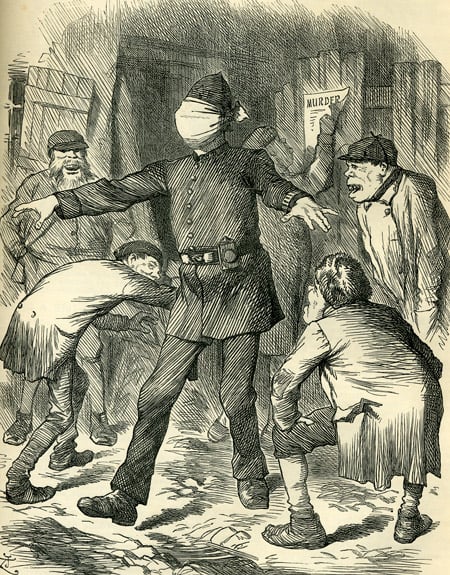

However, what attracted the ire of the journalist and which, no doubt, had a similar effect on the sensibilities of the people in the district where the crimes were occurring, was that the attack had taken place at 9am on a bright winter’s morning, in a densely-crowded district and that, despite the fact that a hue and cry had been raised almost immediately, the assailant had managed to get clean away in a district where, so the article observed, “we have been assured the police are keeping vigilant watch in redoubled numbers” for the “ruffian supposed to be the real Jack the Ripper.”

The fact this had, apparently, been allowed to happen was, so Reynolds Newspaper informed its readers, “one of the gravest and most depressing facts that it has ever been our duty to record.”

“We ask,” read the indignant article. “Where were the police, and, we may add, the vigilance committee, which has recently shown signs (at least in the newspapers) of new vigour?”

A PEEK AT THE STREETS

What is intriguing about articles such as this is the opportunity they afford us to, quite literally, gain a glimpse of the frenetic activity that was happening in the area in the wake of another crime. Indeed, the article then goes on to report on the police activity in the area in November 1888:-

“We have been assured that specially-trained officers, both in uniform and plain clothes, are daily and nightly on the watch against another crime – or,rather, against the escape of the criminal, for the police have admitted the hopelessness of preventing the perpetration of the deed. Let only the miscreant rip up another victim, said they, in effect, and his capture will be certain.

Well, another was provided in Miller’s Court, and because the murderer – quite naturally, of course, from the point of view of the game between him and authority – varied his tactics, he escaped once more.

Miller’s Court is now guarded night and day by the police. Mitre Square is also under watch and ward, and Berner Street has a double share of protection.

But are the authorities simple enough to imagine that so skilful and wary a ruffian – that anyone, indeed, but the stupidest and most reckless of criminals – would attempt to repeat his barbarous experiments in one of these places – for the present at least?

Must he oblige the police by committing the murder under their noses before they arrest him? It would really seem so.”

NOT IMPRESSED BY THE POLICE

Evidently Reynolds Newspaper along with, it must be said, several other newspapers, was not in the least bit impressed by the police endeavours to catch the perpetrator of the Whitechapel murders.

Indeed, the writer of the article was most certainly not pulling any punches when he reported that the police:-

“have exhibited an incapacity that amounts to imbecility in all their methods: and whether it is the outcome of divided counsels in high quarters or sheer incompetence, the result is the same, and a brutal murderer is given what seems absolute impunity to practise his horrid crimes. This is a terrible outlook for the poor of the East End, but we are afraid that it must be accepted.”

THE POLICE ARE AT LOGGERHEADS

The article went on to inform its readers that they must reconcile themselves that “all is discord, confusion, and imbecility.” That the journalist responsible for the article had little, in fact no, faith whatsoever in a police force that was riven by internal strife is more than evident.

In reference to the higher echelons of those charged with hunting the killer, for example, the feature had this to say:-

“The authorities are at loggerheads with each other: the Chief Commissioner [Sir Charles Warren] has resigned: the head of the Criminal Investigation Department [Dr. Robert Anderson] is new to the duties and no one knows anything about him: his predecessor [James Monro] is located somewhere in Whitehall under the wing of an incompetent Home Secretary [Henry Mathews]”

In short, the police have lost the plot and, under the current regime, there is no hop of them getting it back, let alone of them preventing further horrors in Whitechaepel.

THE POLICE HAVE FAILED MISERABLY

The journalist responsible for the scathing attack was at pains to assure his readers that he had “presented the matter as it is, without exaggerating a single point or going beyond the bare record of the facts as reported.”

But, when the results – or to be more precise the lack of them – of the police handling of the case were taken into consideration, there was only one conclusion that could be drawn:-

“The police have failed miserably. They have obtained grace again and again from a horror-stricken public, and almost in so many words they have dared the human fiend of Whitechapel to try his hand once more.He did so seven times, and with all their assurances he is as free as ever to pursue his hellish work, and may pursue it periodically. for aught the police can do, for years to come.”

ROLL ON 1889!

Reading these newspaper attacks on the police, you can’t help but feel sorry for the likes of Inspector Abberline and Inspector Reid, who were pursuing their inquiries into the long winter nights with few results and precious little gratitude or sympathy being shown towards them. It really must have sapped their morale.

Evidently 1888 had not been a good year and, as the last week of November approached, they must have been looking forward to the prospect of a new year and, hopefully, a fresh start, in their hunt for Jack the Ripper.