It is always intriguing to read bygone accounts from journalists who, at the time of – and in the years proceeding – the Jack the Ripper murders, ventured into the East End of London in order to report on the conditions, sights, sounds, smells and people that they encountered.

One such article appeared in the Daily News on Monday the 18th of May 1903 and featured a report from a journalist who had set out to find the worst street in London:

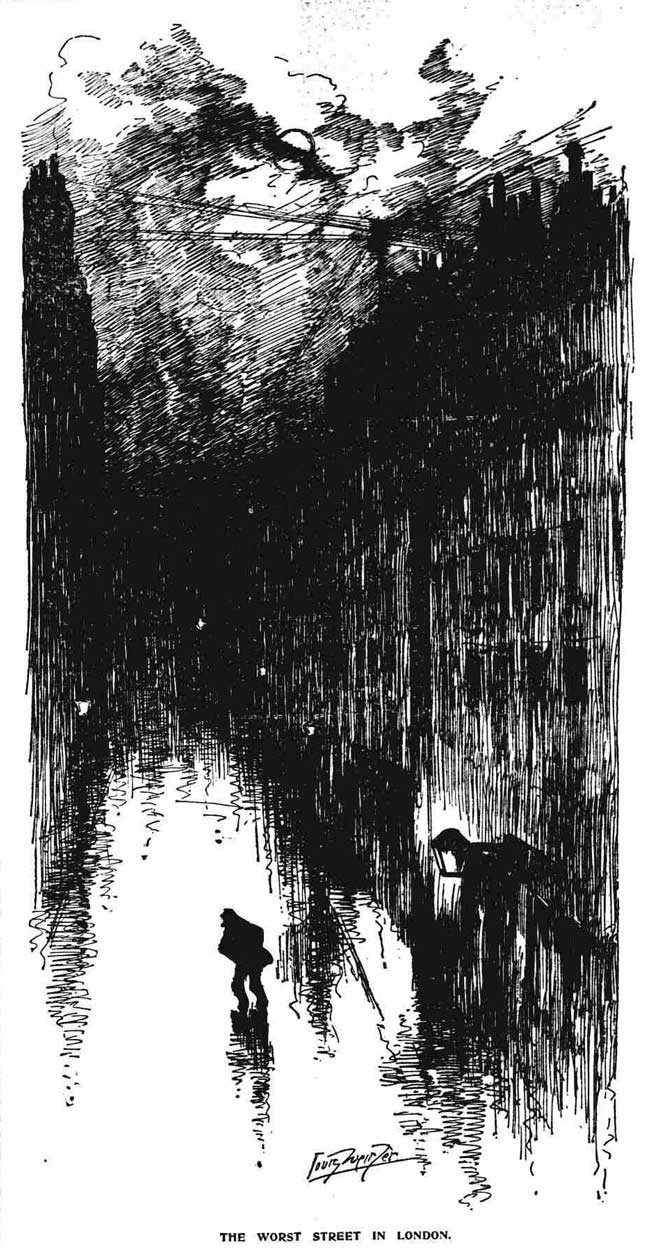

THE WORST STREET IN LONDON

“The East-end was a region known to me only superficially in its daylight aspect.

It was my purpose to see it at night: and this is the story of solitary wanderings beyond Aldgate that began soon after midnight, and continued till five o’clock on a clear, grey Friday morning.

Expectation was falsified by all my experiences.

Yet, on looking back, it seems that nothing could well be other than it proved to be.

THROUGH WHITECHAPEL HIGH STREET

In the beginning I sauntered down the thoroughfare – superb in its breadth and radiant with electric light – that begins as Whitechapel High-street and presently enters into the new name of the Mile-end-road.

Nothing happened all the way.

My impressions were merely negative.

A few quiet souls were abroad – carters and others late to leave their work, as it seemed – but there was no quarrelling, no shouting, no man at mutiny with himself or the world.

Nor, beyond St. Mary’s church, was any girl or woman to be seen; while human misery was only once suggested – by the drooping figures on the circular seats outside the London Hospital.

A POLICEMAN’S ADVICE

Hard by the People’s Palace I took counsel with a policeman.

Where could I have some glimpse at the lawlessness, crime, and horror that made up the East-end of my imagination?

All his talk proved in harmony with the ugly suppositions that appearances so far had left lamely unconfirmed.

This street and that street – naming two within easy reach – were regions of especial terror, not to be traversed by respectability without uniformed guardianship.

And, in our growing friendliness, the policeman volunteered as my pilot to the nearest little Hades.

He stood at the end of the street and pointed.

“A wonderful rough place, that, sir!”

I gazed down the short perspective of shadows, gas light, and solitude wherein two cats moved furtively.

WHERE ARE THE ROUGH PEOPLE?

“But where are the rough people?”

“Oh, they’re all gone to bed long ago.”

Certainly it was close on two o’clock – but all gone to bed!

I grew a trifle impatient.

Ratcliff-highway and Wapping – I suggested – were they not places of nocturnal disorder and alarm?

Yes, assented the constable, there were sights to be seen there; but his urgent recommendation was that, at such an hour I should not venture alone into that quarter.

He even urged that the journey thither would not be unattended by risk.

Perhaps, already a vague scepticism was growing in my mind – at any rate, I reflected that, having come out to see the East-end by night, it behoved me to see it thoroughly.

Finding my purpose set, the policeman gave me directions how to go, thoughtfully figuring out my course through broad thoroughfares, where, he apprehended, the minimum of harm would befall me.

And so, good morning, and away on our opposite beats.

LOST IN THE ABYSS

My first turning must have been a false one, for it ended in a narrow street, which led into another, and that into a third, so that in ten minutes I was lost to all knowledge of my whereabouts, unable to retrace my steps, equally unable to determine from among the multiplicity of tiny thoroughfares which would assist my progress.

Then fear came.

Suppose there was solid grounds for the policeman’s cautions, and suppose from among the shadows some unknown menace should spring out upon me?

Lawlessness could ask no easier prey; I had not so much as an umbrella wherewith to guard my person.

ON THROUGH THE MAZE

On and on I walked, taking turnings at random in that maze of right angles.

Coming to a thoroughfare of broad dimensions, I found two constables standing together in the middle of the roadway.

The large building with the lights, they told me on my seeking topographical information – was the Thames Police Court; and their stern, inquiring looks made manifest a desire to learn something of myself, and why the small hours found me drifting ignorantly through that end of the town.

Then, on full disclosure of my intent, there came further vague testimony to the fearsome social elements I had sought for so zealously without finding.

I told them my thought of the matter – that their imaginations were haunted by bugbears; that they could not see the facts as they were for so persistently conceiving them otherwise – and at this bold polemical attack, followed as it was by a demand for definite statistics of recent assaults, they talked in a different key.

ROWDYISM AND VIOLENCE

Now I was informed that a new face had come upon the East-end of recent years.

Rowdyism and violence had gone with good wages and the robust physique they sustained.

DORSET STREET, SPITALFIELDS

I should find Ratcliff-highway as decorous a thoroughfare as any I had traversed, and this was coupled with the assurance that, if I desired to see the East-end at its blackest, I must visit Dorset-street, Spitalfields.

That, they assured me, was beyond all comparison “the worst street in London.”

For Whitechapel, accordingly, I shaped my course, passing along Commercial-road East, where parish scavengers were busy with their brooms, and the only vehicles were vans piled high with vegetables, moving slowly through the night towards the wholesale markets.

A COFFEE BREAK

To a coffee-stall at the junction with Whitechapel High-street – the first I had seen that night – I gratefully repaired for refreshments and thither presently came a shambling figure with a piece of paper in his hand and a humble petition on his lips.

Might he – and his head turning loosely on his neck, bent humbly towards the keeper of the stall – might he take a light for his pipe; and to make manifest that he was not asking for a match, and would put no one to any trouble, he extended his piece of paper towards the bars of the little cooking range.

In that purely explanatory attitude he awaited the proprietorial decision, which was in his favour: and as he fumbled at the fire I suggested a cup of coffee and a hard-boiled egg for his acceptance – a courtesy well received.

We fell into an easy chat, and I asked him how often he had been to prison (only once – when he was in the Army, he replied), and whether he managed to get any sort of fun out of life.

The strangeness of the abashed smile with which he apologetically explained that he didn’t, graphically indicated that his smiling muscles had long been out of use.

But I am describing this incident merely to describe another.

A CONSTABULARY TRIO

As we were conferring together I was aware that three policemen had mysteriously accumulated against the shop shutters a few paces behind us; and when, our meal concluded, I had bidden my friend good-bye, curiosity impelled me to step back and engage the constabulary trio at close quarters.

It was even as I had supposed.

They looked me up and down with hard ill-favour. nor were they in any haste to answer my simple question most politely asked – where, would they kindly tell me, was Dorset-street?

Nay, in the eye of the one to whom I had more particularly addressed myself, there was an ugly glint plainly signifying that, for two pins, he would arrest me.

SLUGGISH, SLOUCHING FIGURES

In Commercial-street I passed several sluggish, slouching figures, each the counterpart of my coffee-stall companion.

Having failed in the dark to recognise Dorset-street, I was fain, on coming abreast of Spitalfields Market, to seek further guidance from still another constable.

A cheerful fellow, he took great delight in my company on learning the nature and object of my wanderings.

Most obligingly he discoursed of thieves that dwell thickly thereabouts.

A REMINDER OF OLIVER TWIST

One of his memories was of an old gentleman who instructed youth how to remove trifles from the pockets of unsuspecting citizens; and the whole affair had so familiar a ring that I came near to inquiring whether, of the proficient pupils who had fallen into police hands, one answered to the name of Charlie Bates.

The evil reputation of Dorset-street was so graphically confirmed in this quarter that, fear returning with growing sleepiness, I was in no urgency to penetrate its secrets.

Yet light was soon visible in the eastern sky, and that sight gave me heart for the enterprise.

INTO DORSET STREET

It was dark and dismal in that narrow street of tall houses.

Cats were eating garbage in the roadway.

That black mass of rounded shapes terms the way – men crouching in a doorway – gave no heed to the solitary passerby.

A glow of ruddy fire-light came from the spacious kitchen of a common lodging-house, separated from the pavement only by upright bars.

Grey smudges over a first-door window proved on near inspection to be fairy lamps – in that place, with their crust of grime, an eloquent contradiction of festivity.

At the end of the street fortune threw me into communion with a desirable policeman.

He knew the place by heart, and, because of sympathy and a clear mind, he understood its people.

TRAGIC SIGHTS

Brusque and fearless in conversation with me, his soul was full of tears for them.

He showed me what there was to see with never a word spoken.

Walking along the street, he pushed open the doors with his knee, flashing his lantern into the blackness within.

And I saw heaps of rags lying on the floor, and sometimes one of the heaps would quiver and heave, and out of those noisome draperies the haggard and revolting travesty of a human face – once a woman’s – would emerge, blinking at the sudden light.

It was as though this robust and strenuous man, charged with feelings he could not utter, was acting as showman in the infernal regions.

MILLER’S COURT

There is magic in comparisons.

After what I just had seen, the court in which Jack the Ripper slew his last victim – at another time a spot to compel a shudder – had only a mild historic interest.

Also was there but a subdued taint of tragedy in the aspect of a Dorset-street parlour wherein, two years ago, one wretched woman murdered another.

A FINAL EXPERIENCE

But I was to have a final experience of the unthinkable.

My policeman left me to enter a house midway up a narrow court, it being his practice at that hour to rouse a man who, despite a long record of penal servitude, now had “another chance” in a job at the market.

During my companion’s absence I explored the court, wherein I encountered an appalling stench, besides seeing – and the brave pathos of the sight brought my heart into my mouth – a horseshoe displayed over one of the doors.

Reappearing, the policeman motioned me to accompany him back into the house.

I entered that cavern of darkness, climbing the rickety stairs at his heels.

On the landing above be poured his lantern light into a narrow recess under the staircase.

There, wedged dexterously into the space, lay two men with a cat asleep on one of their shoulders; while at their feet, and at ours, was another of those heaps of collapsed rags I now know to be women.”