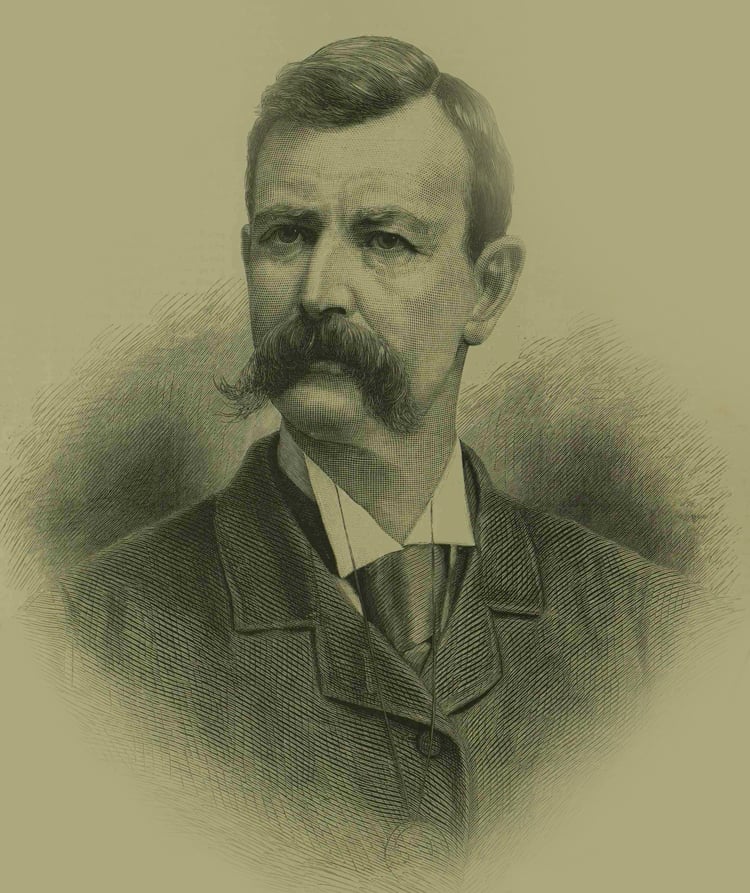

The “Bloody Sunday” unrest of 13th November, 1887, was, arguably, one of the most shameful occurrences during the tenure of Sir Charles Warren as the Chief Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police.

Many newspapers were united in their condemnation of the police behaviour on the day, and the reaction was one of the reasons why the radical press was so ready to heap ignominy on the police in general, and Sir Charles Warren in particular, during the Jack the Ripper murders when they occurred the following year.

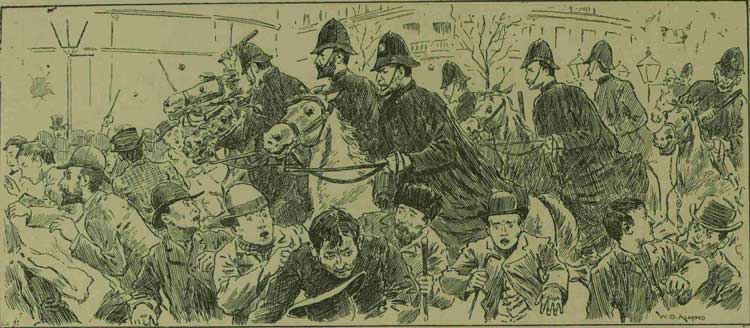

SUNDAY TRAFALGAR SQUARE POLICEMEN IN ACTION

The Peterhead Sentinel and General Advertiser for Buchan District published the following article on Tuesday, 22nd, November, 1887.

It was written by a journalist who had been caught up in the carnage and who, therefore, was able to provide a first-hand account of the events as they had unfolded on that notorious Sunday afternoon:-

“London, Saturday, November 19th. I went to Trafalgar Square last Sunday to witness the meeting between the “police and the people.”

Fortunately, I did not get my head broken. I say fortunately because broken heads were the order of the day, and it was due to luck rather than to good management that I did not swell the roll of victims.

I was wedged into a dense crowd in the middle Northumberland Avenue when a band of mounted policemen dashed into us at full gallop and belaboured right and left with their batons at the unfortunate crowd.

MANY CASUALTIES RESULTED

An old man alongside got a severe blow to the forehead, and, with the blood streaming down his face, I assisted to carry him on to the pavement, where a Police Sergeant humanely took him in charge and had him sent off to Charing Cross Hospital.

There were a good many other casualties as the result of this charge, which occurred just after four o’clock.

Several people were knocked down by the horses, whilst others suffered from the brutal blows administered the police.

DISCRETION IS THE BETTER PART OF VALOUR

As I saw that arrangements were being made for a fresh charge down Northumberland Avenue, and that there seemed every evidence of a “shindy,” the Life Guards having just ridden up Whitehall with a magistrate at their head prepared to read the Riot Act, I determined to act upon the time-honoured motto that “discretion is the better part of valour.”

I did not quite see the use of attempting to repel a charge of police cavalry armed with batons, by the aid of my umbrella, said utilitarian adjunct of piping times of peace being absolutely the only weapon, lethal or otherwise, with which I was equipped.

Accordingly, I was trying to find my way out of the crowd, when a friendly voice halloed to me from a first-floor window in the large building at the corner Northumberland Avenue and Whitehall. This, I suddenly recollected, was until recently the premises of the National Liberal Club, but the Club having moved into still more spacious quarters, the old premises are to let.

THE ASSEMBLY WITHIN

After a brief parley, the stout oaken door was opened by the caretaker and I passed inside to find myself in the presence of a more or less distinguished company, who were gazing from the various windows upon the remarkable scene in the Square below.

At one window was the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette (Mr Stead) and his staff, at another Mrs Cunninghame Graham, wife of the member for one of the divisions of Lanarkshire, who had just been assaulted by the police and led captive within the cordon of police guarding Trafalgar Square, and at yet another was a group of well-known journalists and several detectives who took a fine bird’s-eye view of some active friends of theirs, whom they suspected of attempting to ply their vocation in the midst of the crowd underneath.

LOOKING OUT FROM THE DARKNESS

It was a somewhat weird sensation I experienced standing in the darkness (for we had no light of any sort) and looking out upon the scene of tumult raging all around the square.

By the brilliant light of the numerous gas lamps we could discern quite clearly what was going on, and sometimes when we could not see we could hear. We could tell the dull thud of a policeman’s staff across the back or skull of a human being, when we could not see by whom the blow was administered.

We saw men struck down prostrate under the hoofs of the horses, and we could see them being raised up by their friends and carried to the hospital.

THE POLICE BEHAVIOUR

How did the police behave?

If that question were put to me in the witness-box I fancy I could answer it as well as anybody.

My readers are no doubt perfectly well aware that all this ruction of which I have been speaking arose out of an order by Sir Charles Warren, the Chief Commissioner of Police of the metropolis, prohibiting the holding of any public meeting in Trafalgar Square, and directing that any organised procession attempting to approach the Square should be broken up.

The police, of course, were only obeying instructions.

Their orders were to prevent people assembling near the Square and to keep the way clear.

I will admit that, before resorting to force, they did try gentle and persuasive means.

When people first began to cluster about the pavements the foot policemen came along and in a manner which was quite bland sang out “Pass away, gentlemen, please” – “pass away” being invariably the phrase of the London “bobby”, and not the oft-quoted “move on,” which has done duty in many a satirical tale and ditty.

THEY BEHAVED LIKE MADMEN

It was not until the crowd became dense that the mounted police were ordered to charge, and let me say at once that it is against the mounted police that the accusation of gross brutality may with fairness be directed.

They behaved like madmen, rushing hither and thither and striking out wildly and blindly with their batons.

They spared neither gentle nor simple, and I myself saw them hand over to the foot police several harmless people whom they had mercilessly pounded with their staves and fists.

As an evidence of their recklessness, one of them drove his horse right through the large plate glass window of the ground floor of the building where I was, and an Inspector, thinking the crowd had done this, gave orders for a fresh charge down Northumberland Avenue.

At one time we were alarmed by a cry that our building was being set on fire. This was shortly before five o’clock when the tumult was at its worst. The cry was originated by some mischievous roughs in the crowd lighting matches and throwing them in the broken window.

Fortunately, they did not do any damage, and half a dozen policemen with drawn staves having been stationed in front of the window, any further attempt at mischief was frustrated.

It was close upon six o’clock before the Square was rendered comparatively clear, and we left the building.

THE FOOT GUARDS WERE READY

It was then that I learnt from an Inspector of Police that the Foot Guards, who were called out and stationed by the National Gallery, would have been ordered to charge the crowd with fixed bayonets if the people had not cleared away or been dispersed by the police.

It had been arranged before-hand to read the Riot Act at six o’clock and then give the order to the military to charge.

Fortunately, the dispersion of the crowd at an earlier hour averted frightful carnage, for not only were the Horse Guards provided with swords, and the Foot Guards with bayonets, but each man of the latter also carried his ammunition pouch with a certain number rounds of ball cartridge.

THE WOUNDED TREATED

At Charing Cross Hospital over a hundred persons were treated for wounds.

The house surgeon, whom I afterwards spoke to, knew that it could not be otherwise, informed me that nine-tenths the wounds were caused by policemen’s staves.

The crowd was absolutely defenceless, many having not even a stick or an umbrella to defend themselves with.

ATTACKING DEFENCELESS PEOPLE

It was the wanton attack they made on defenceless people that constitutes the gravest of the charges against the police cavalry.

The hooting of the mob and the cries of “cowards” and “brutes” only inflamed their ferocity, and led them to indulge in fresh acts of barbarity.

One man I saw held by the hair of the head by one policeman while another rained blows on his head and shoulders with his staff. The man had to be taken off to hospital, and it is a marvel to me that his skull was not fractured.

IN DEFENCE OF THE POLICE

There is something to be said in favour of the police, who are, after all, human beings and not machines.

These men had been on duty, some of them from ten o’clock in the morning, without rest, and I almost believe without refreshment.

It was a cold day, and, added to this, the hooting of the mob was calculated to irritate and inflame those feelings of resentment to which policemen, in common with other human beings, are subject.”