An oft unmentioned aspect of the Jack the Ripper murder spree is the political climate against which it was played out.

The 1880’s was a decade of great unrest. Increased foreign competition against British industries had seen the spectre of mass-unemployment rear its head over many cities.

This was particularly noticeable in the East End of London where, in addition to overseas competition, a huge wave of immigration had resulted in direct competition within the local workforce; and many agitators had been actively encouraging the “working men” of the East London to bare their teeth and start demanding their fair share of the spoils of Empire, from which many of them had found themselves excluded.

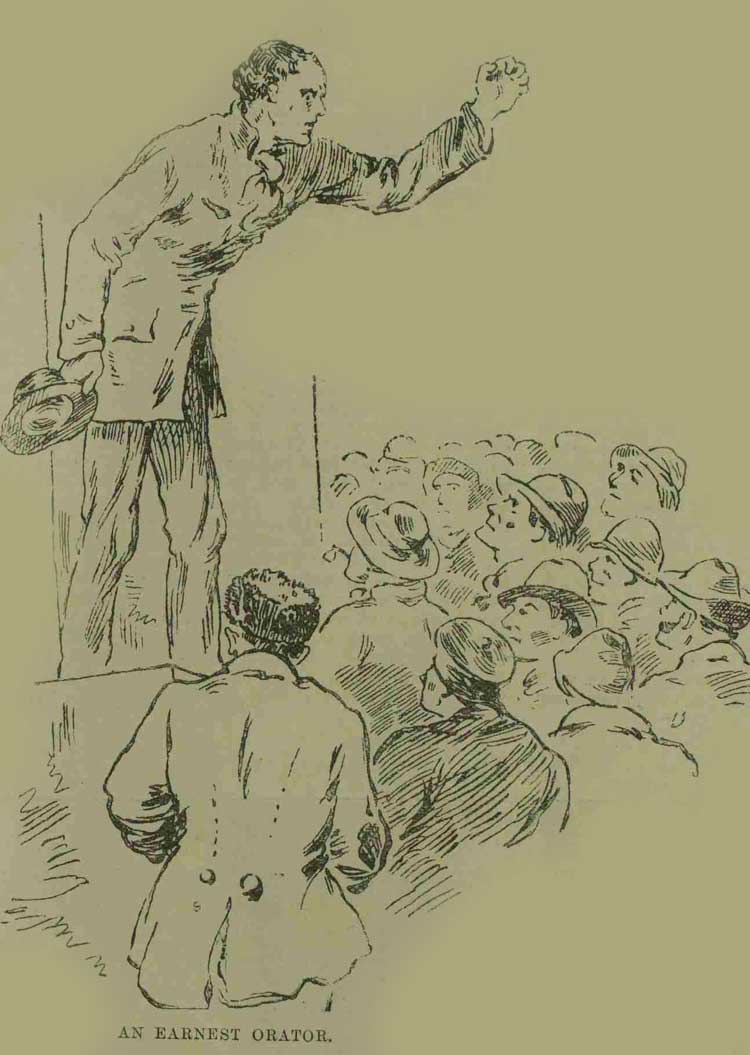

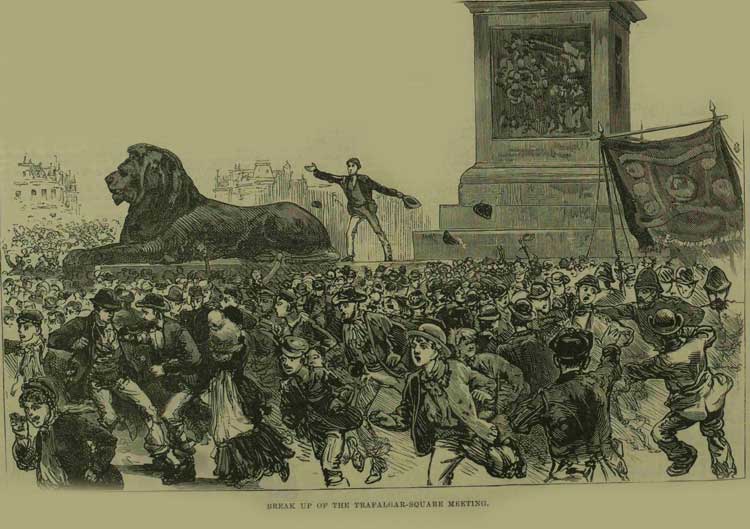

As a result, the people of the East End – or at least some of their more vociferous elements – had been gravitating towards Trafalgar Square, where several Socialist and radical organisations were organising mass meetings at which radical speakers were encouraging them to make their voices heard.

EAST LONDON MOBS

The fact that several of these meetings boiled over into full scale rioting, meant that the mainstream media had begun to demonise the “East End mob” – which, in fairness, were made up of men from all over London, but which were being largely portrayed as am outgrowth of the East End – and, as a consequence, Trafalgar Square became a hotbed of agitation, that, in turn, led to several confrontations between the political status quo and the radicals.

It was against this background of political unrest that the Whitechapel murders occurred, and, as they were reported, and sensationalised, more and more by the mainstream press, Jack the Ripper became the very personification of all the fears and prejudices that the middle and upper classes held towards the residents of the East End.

RIOT IN TRAFALGAR SQUARE

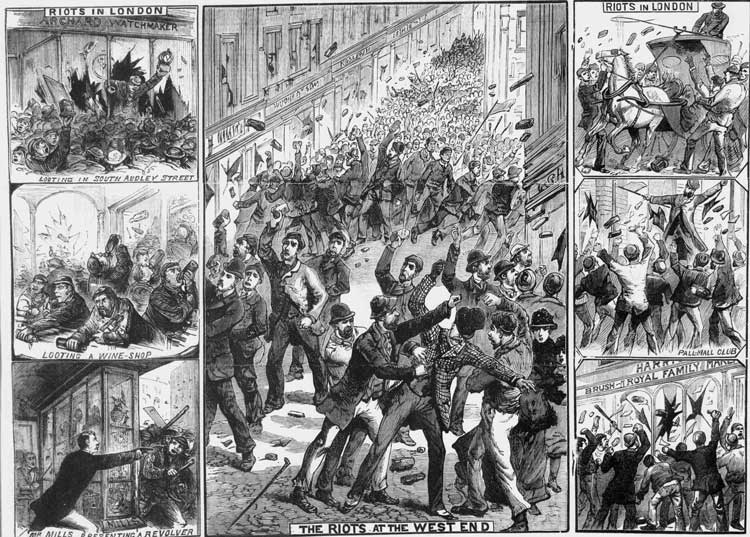

On Monday February 8th, 1886, a meeting in Trafalgar Square, sparked a riot in the streets of the West End of London, that saw an angry mob rampage through some of the Victorian Capital’s most respectable – and well-heeled – streets, leaving a trail of broken windows and whole scale destruction in its wake.

THE POLICE COMMISSIONER RESIGNS

The fact that the police were unable to contain the violence sent waves of trepidation coursing through many middle and upper class households, and sparked a huge amount of press criticism of the then Police Commissioner, Sir Edmund Yeamans Walcott Henderson (1821-1896), whose immediate response was to resign his post.

SIR CHARLES WARREN TAKES OVER

He was replaced by Sir Charles Warren, who, over the next two years, would demonstrate his mettle, and his determination to prevent mob-rule from occurring on the streets of London again, by putting down similar unrest with such ruthless efficiency that the radical press would turn against him and would then use the Jack the Ripper murders, and the police inability to catch the perpetrator, to attack him on an almost daily basis.

A FULL REPORT ON THE DAY OF RIOTING

In its edition of Saturday the 13th of February 1886, The Illustrated London News, treated it readers to what was, quite literally, a blow by blow account, of the day’s events:-

RIOTS AT THE WEST-END OF LONDON

A deplorable outbreak of silly and mischievous mob-violence, attended with wanton destruction of property in some of the most fashionable streets of the West-End, took place on Monday afternoon.

It arose from an open-air meeting of the unemployed and distressed men of the labouring classes, improperly convened in Trafalgar-square.

The exciting and provocatory speeches of certain fanatical orators, belonging to the Socialist Democratic faction of physical force Revolutionists, stirred up the feelings of some part of this vague assembly, and furnished the ill-disposed, of whom many, probably. were neither in distress nor anxious for honest work, with a pretext for acts of outrage, not unaccompanied with robbery amid the confusion that ensued.

A RAMPAGING RABBLE

A rabble of several thousand men and youths, bearing little resemblance to any of the London working classes, suddenly poured from Trafalgar-square through Pall-mall, up St. James’s-street, and along Piccadilly to Hyde Park-corner, turned east of Park-lane, and got into the Grosvenor-square neighbourhood, visiting South and North Audley-street, and everywhere doing all the damage they could to shops and houses.

The police seem to have been taken by surprise, for they were not in sufficient force to stop this rapid movement, which might easily have been arrested at certain points, by a barrier formed of two or three hundred disciplined constables with their truncheons.

ASSEMBLED IN TRAFALGAR SQUARE

The number of people assembled in Trafalgar-square, at three o’clock, was estimated at fifteen or twenty thousand.

Part of these were really East-End labourers, men of the building trades, or from the docks, or artisans out of employment, who intended merely a peaceable or orderly “demonstration.”

Some were organised in processions, with flags and bands of music.

Another part, which may not have exceeded one-tenth of the multitude, consisted of mere idlers and reckless street vagabonds, ready for any chance of making a disturbance: and these were, no doubt, the actual rioters at the close of the meeting.

THE POLITICAL FACTIONS

The proceedings of the original “demonstration” were organised by the Labourers’ Union, of which Mr. Kenny is the secretary, with the object of demanding that, public relief works, for unskilled labour, should be started by Government, and Parliament should amend the laws relating to land.

A party of “Fair Traders,” claiming Protectionist fiscal legislation to exclude foreign manufactures, had apparently seized this opportunity to enforce their views of commercial policy upon the minds of working men.

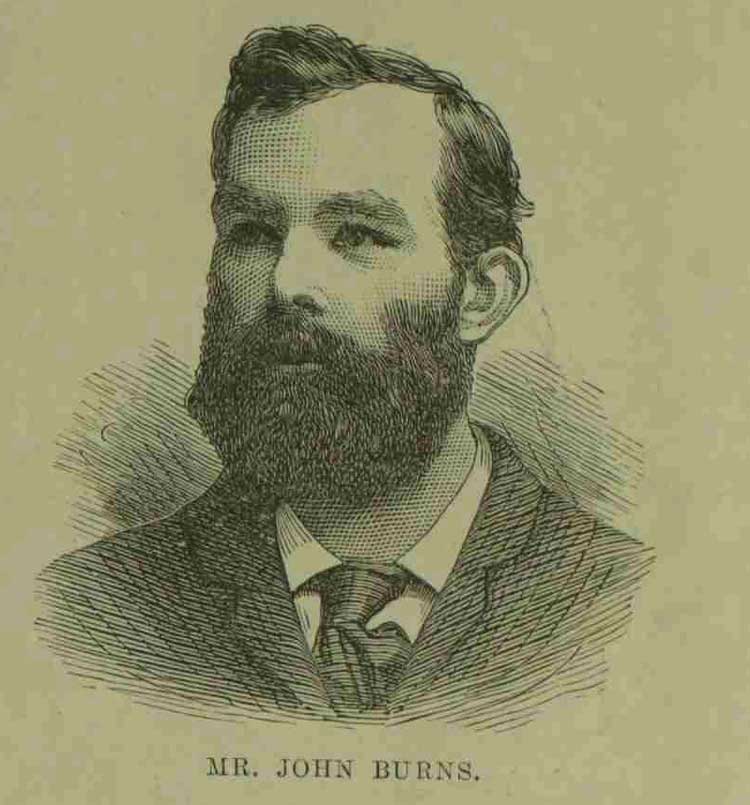

Lastly, there was the Revolutionary Communist party, headed by Mr. Hyndman and Mr. John Burns, who were certainly not acting in concert with the two former sections, and the three different sets of speakers vehemently contradicted each other; but there was a loose mass of senseless ruffianism, caring not for the arguments of either party, which finally broke away to indulge in deeds of havoc, and to spread alarm in a part of town frequented by the upper classes.

NOT ALARMING AT FIRST

The proceedings in Trafalgar-square. for an hour or more, around the Nelson Column, in front of the National Gallery, and at the stone balustrade above the fountains, where the various sections of the assembly heard their respective orators, and assented to several resolutions, did not seem alarming.

They were conducted in such a manner that no disturbance was anticipated.

The force of five hundred police in attendance had been deemed adequate to deal with any emergency which might arise.

Yet, during these proceedings, the scene presented in Trafalgar-square was extraordinary.

The whole of the middle space, where the fountains are, was densely packed with people: the roadways on each side were filled, the steps of St. Martin’s Church were thronged, and towards Pall-mall East, were spectators, apparently taking no part in the demonstration.

THE LABOURERS’ UNION AND FAIR TRADERS’ MEETING.

The meeting held by the original promoters was led by Mr. Kenny, with whom appeared to be associated the East-End Fair Trade Leaguers, Messrs. Lemon, Peters, and Kelly, with Mr. Cook, late Conservative candidate for Battersea, and Mr. Albert Charrington.

The platform stands were made on work benches at the north end of the square.

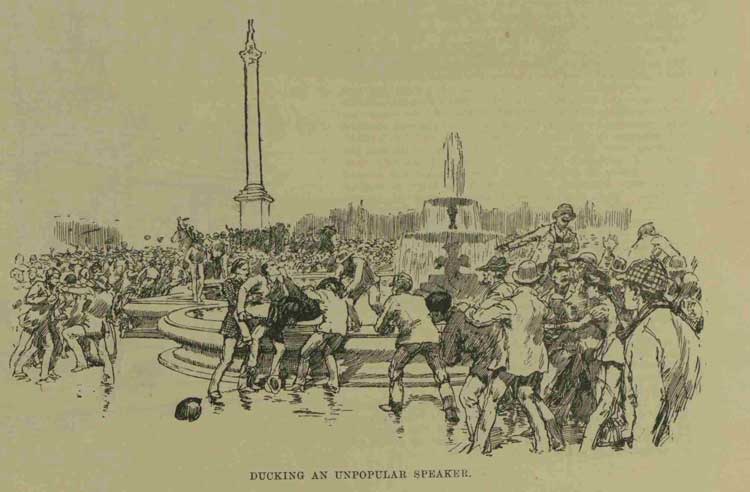

A person named Johnson, known as a Clerkenwell Democrat, coming to one stand, was denounced and ill-treated.

Another speaker was thrown into the fountain – platform and all.

OUT OF WORK LABOURERS

At the chief platform the Fair Leaguer, Mr. Peters, was supposed to take the chair, and the audience here had the largest number of bona fide out-of-work labourers, and but few roughs, who, indeed, were kept in awe and order by the steady determination of the workers to have no disturbance in their midst.

Mr. Peters said that he hoped the rich would see the numbers wanting food, and was met by several voices exclaiming, “We want work, not charity.”

A set of resolutions was then moved by Mr. Kenny, supported by Mr. Albert Charrington and Mr. E. R. Cook, requesting Her Majesty’s Government to start useful public works for the unemployed; also, that Parliament should encourage the employment of British capital in British rather than foreign enterprises, and take measures to relieve our distressed agricultural interest; and that a Ministry of Commerce and Agriculture should be appointed, and fair play should be given to British industry, against the disastrous effects of hostile foreign tariffs and of foreign State bounties on products imported into the British market.

These resolutions were carried by acclamation at three different platforms; but that occupied by Mr. Peters, Mr. Kenny, Mr. Charrington, and Mr. Cooke broke down immediately afterwards, so that this part of the meeting dispersed in some confusion.

THE SOCIALIST DEMOCRATS’ MEETING.

There was a menacing roar of voices as a man with the red flag mounted the stone-work overlooking the fountains, and all faces turned in that direction.

Mr. Burns had a loud voice, which could be heard at a great distance.

He declared that he and his friends of the Social Democratic Federation were not there to oppose the agitation of the unemployed, but to prevent people being made the tools of paid agitators in the interests of the Fair Trade League.

He went on to denounce the House of Commons as composed of capitalists who had fattened upon the labour of the working men, and in this class he included landlords, railway directors, and employers, who, he said, were no more likely to legislate in the interests of the working men than were the wolves to labour for the lambs.

To hang these, he said, would be to waste good rope, and as no good to the people was to be expected from these “representatives,” there must be revolution to alter the present state of things.

The people who were out of work did not want relief but justice. From whom should they get justice? From such as the Duke of Westminster and his class, or the capitalists in the House of Commons and their classes? No relief or justice would come from them.

The working men had now the vote conferred upon them. What for? To turn one party out and put the other in? Were they going to be content with that while their wives and children wanted food? When the people in France demanded food, the rich laughed at those they called the “men in blouses”; but the heads of those who laughed soon decorated the lamp-posts.

ALL THE OUT OF WORK RAISE THEIR HANDS

The leaders of the Social Democratic Federation wanted to settle affairs peaceably if they could; but if not, they would not shrink from revolution.

A large part of the audience heard all these violent sayings without approval or rebuke, and then the speaker asked those out of work to hold up their hands. Nearly all the hands were held up.

Mr. Champion, who was chairman of the meeting at the Holborn Town hall last week, called by the Social Democratic Federation, the next speaker, followed by John Williams, the man who was imprisoned for resisting the police at an East-End Socialist meeting.

MR HYNDMAN ADDRESSES THE ASSEMBLY

Mr. Hyndman then proceeded to address the meeting, and made a violent harangue.

He said the people out of work were asked to be moderate, but how could they be moderate when they were out of work and starving?

It depended upon them whether they would drive the middle classes to bay, and if they did they would soon win.

Mr. Burns made another speech, in which he observed that the next time they met it would be to go and sack the bakers’ shops in the west of London.

THE TUMULT AFTER THE MEETINGS.

It was only towards the close of the speaking in Trafalgar-square that any signs of violence were shown.

As soon as the speakers stepped down from the small wooden constructions, which had served for platforms, the mob seized the platforms and soon broke up the planks into splintered pieces. These they tossed about over each other’s heads, howling and cheering all the time, and laughing and jeering at the police when they interfered.

Then the crowd moved towards the end of the Strand, and for some time lingered at the block of buildings of which the Grand Hotel forms a part.

They hailed every vehicle which passed, and tried to stop its progress.

The police seemed powerless against the hundreds of persons who constituted the mob, and they did little more than endeavour to protect the cabs, omnibuses, and other vehicles which constantly streamed along the busy thoroughfare.

Once they endeavoured to arrest those who attempted anything in the nature of personal violence, but their prisoners were immediately rescued.

Eventually, however, a reinforcement of police from Scotland-yard and Bow-street came on the scene, and two prisoners were speedily marched off to Bow-street Police Station.

The crowd remained in front of Morley’s Hotel in the square, and continued to hang about for several hours.

THE RIOT IN PALL-MALL.

While the followers of the East-End Labourers’ League, with their allies the Fair Traders, moved off peaceably, returning home along the Strand, a mob headed by several Socialists, one of whom was carrying a small red flag, marched off into Cockspur-street almost unknown to the vast concourse of people on the other side of the square.

This mob, estimated at from 1000 to 2000 persons, proceeded into Pall-mall, and it soon became evident that they were bent upon mischief, and they had loaded themselves with stones and other missiles.

It was remarked by many of the quiet spectators that this mob included a number of roughs who were not really unemployed working men, and that several of those who were apparently acting as ringleaders were respectably dressed.

Mr. Burns, who had presided at the Socialist part of the demonstration, was borne along on the shoulders of several men.

Mr. Hyndman, who was also one of the speakers, was likewise in the crowd.

On their reaching Pall-mall, stones were thrown at several of the clubs in this thoroughfare.

CLUBS ATTACKED

At the Carlton Club the vast crowd, which had now increased to several thousands, stopped, and several of the Socialist leaders climbed on to the railings, and one of them waved the small red flag.

The quickly growing concourse of rabble howled and shouted as they were harangued by their leaders, and hurled stones at the windows.

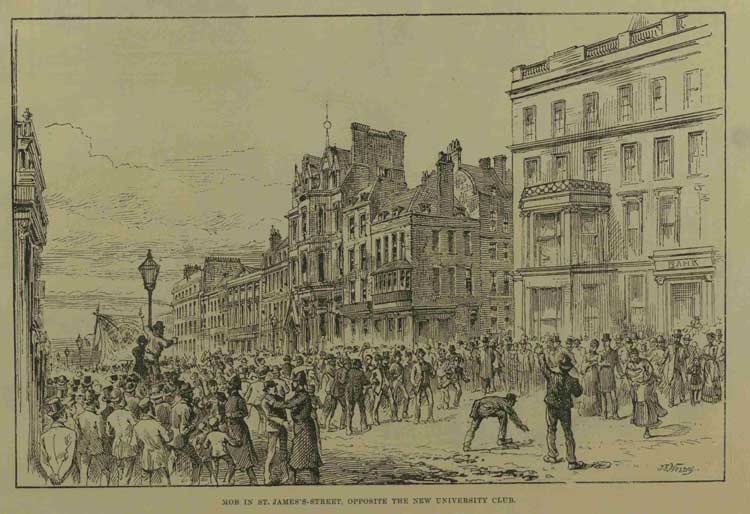

OUTRAGES IN ST. JAMES’S STREET AND PICCADILLY.

The mob swept on furiously round the corner of Pall-mall and up St. James’s-street, and here they threw stones at the windows of nearly all the clubs and some of the shops and private houses.

The first attacked was Arthur’s Club, in which all the windows of the morning-room were broken by stones.

At Brooks’s Club, about forty large panes of glass were smashed.

At the Devonshire Club, eight or nine windows were shattered. and the windows at the New University Club and Boodle’s Club shared a similar fate.

THE MOB ARRIVE ON PICCADILLY

Arriving at the top of St. James’s-street, the mob turned to the left, along Piccadilly, where their violence took a more serious form.

Throwing stones at every moment as they passed, they broke the windows of the Bath Hotel, at the corner of Arlington-street, the windows of the General Stock Exchange, and several shops.

Then they smashed in the windows at the shop of Mr. W. G. Adams, portmanteau-seller.

Some men entered the shop and seized several wood trunks and a small bath. These they carried off and smashed, and threw the bath into the Green Park.

They then turned their attention to the right-hand side of the thoroughfare.

Several windows in private residences were broken.

Much more serious damage was effected when the mob reached Half Moon-street.

At the corner of this street is the establishment of Mr. H. Benjamin, livery tailor, glover, and hosier. The mob here made a determined rush at the windows, which they battered in with stones and other weapons, and then seized the articles of clothing and hosiery which the windows contained.

Turning to the opposite corner of the street, they dashed at the shop of Mr. E. Gallais, wine and spirit and cigar merchant. They served four or five of his large plate-glass windows in the same manner, and some possessed themselves of bottles of spirits and wine.

HYDE PARK-CORNER.

After this act of pillage, the mob went on rapidly in the direction of Hyde Park, throwing stones at most of the private residences, including that of the Hon. E. Marjoribanks, the newly-appointed Comptroller of the Household; and Messrs. Need’s shop, in which works of art are shown, was attacked and the windows broken.

Windows were also smashed at the Bachelors’ Club, at the corner of Hamilton-place, and at the residence of the Duke of Cambridge at the corner of Park-lane.

Rushing wildly onward, the infuriated mob entered Hyde Park, where, for a short time, they were addressed by some of their leaders, who took up a position at the foot of the statue.

Here the mob stopped carriages and turned out their occupants.

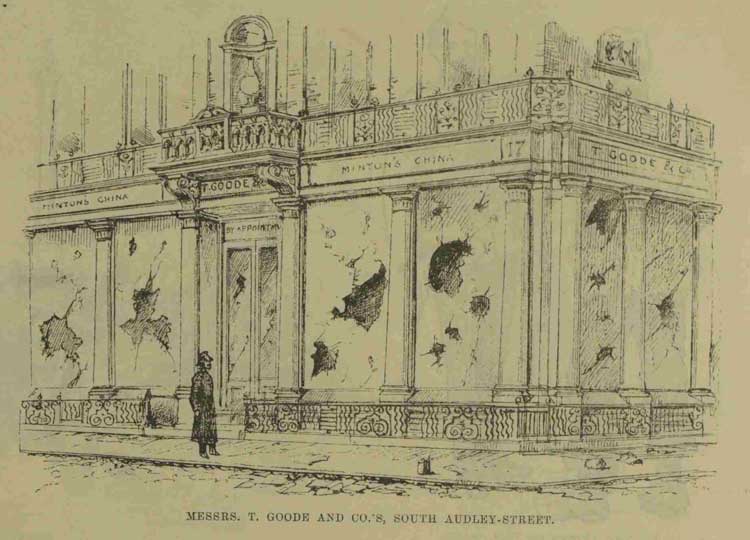

HAVOC IN AUDLEY-STREET.

After a brief halt in the park, they resumed their destructive march.

Rushing madly up the road and through Stanhope-gate, they smashed the windows of Lord Manvers’ residence facing Park-lane, and of Lord Gainsborough’s house at the corner of Tilney-street and Dean-street.

From here they passed along Dean-street into South Audley-street, where there are many shops; they completely wrecked nearly every shop from beginning to end, and the damage to property must amount to a very large sum, while a large quantity of valuable goods were stolen or destroyed.

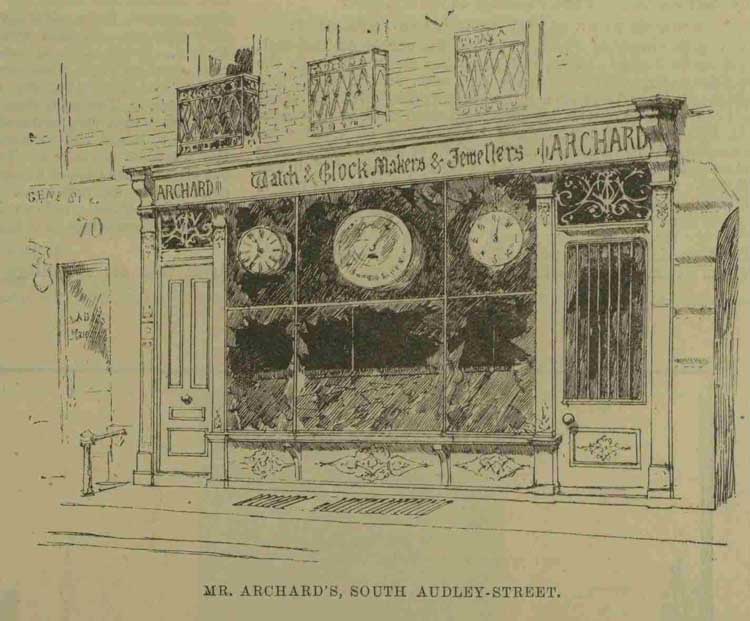

The first shop attacked in South Audley-street was that of Mr. Archard, jeweller.

The windows were smashed to atoms, and watches and jewellery, consisting of rings, pins, studs, earrings, and brooches, to the value of £300 or £400 were torn from their places and taken away.

The large chinaware establishment of Mr. Goode, opposite, also suffered, but the windows were somewhat protected by an iron palisading.

MORE WINDOWS SMASHED

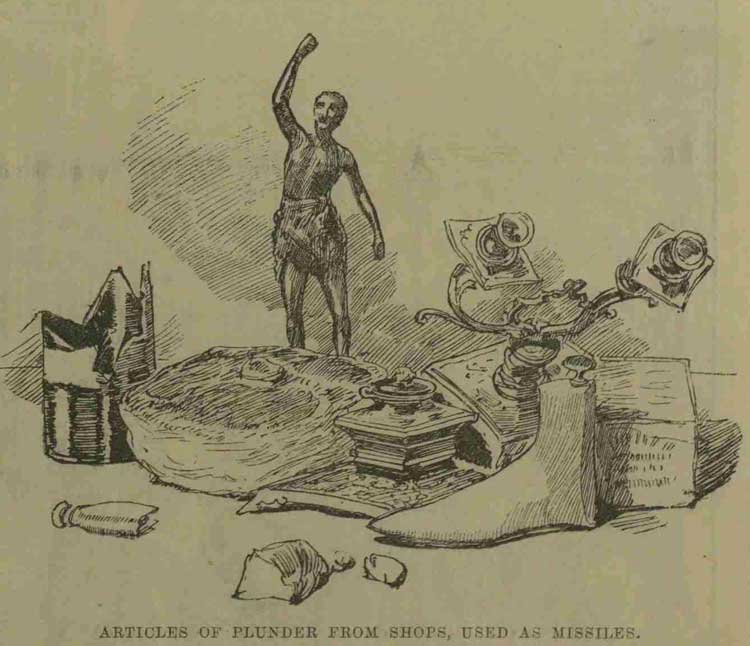

Next the mob smashed the windows at the shop of Messrs. Slack and Co., hatters, throwing some empty bottles of wine and spirits into the shop and damaging the stock.

At an upholsterer’s shop at the corner of Adams’-mews, some valuable silk-covered chairs were destroyed, together with the large plate-glass windows.

The mob proceeded to the shop of Messrs. Cadbury and Pratt, poulterers, and entirely cleared out the open windows of the game and poultry exposed there for sale.

Many of the birds they threw about the street and scrambled for, and others were thrown into shop windows along the street.

From here the mob proceeded to a butcher’s, and seized several joints; it next directed its attention to a boot and shoe shop, treating this with similar destructiveness, and carrying away boots and shoes.

These articles were employed as missiles to attack other shops as they continued their progress.

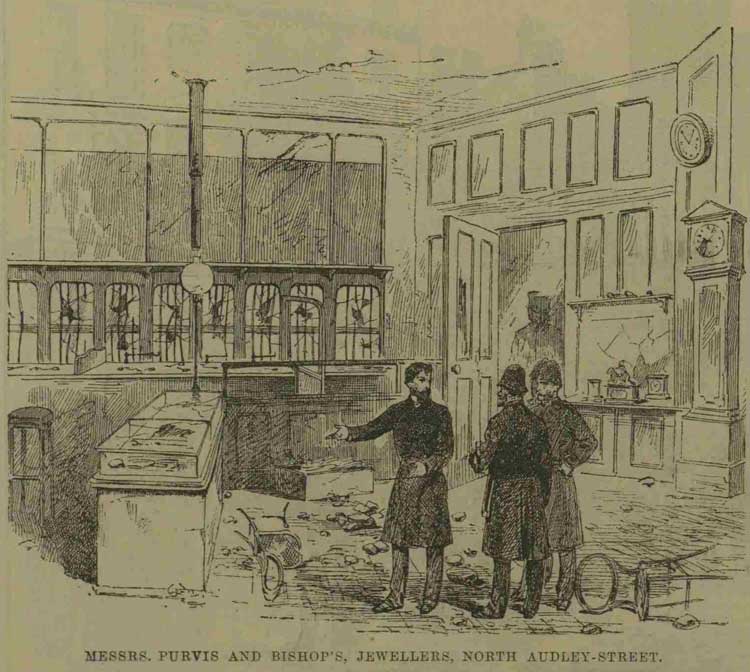

Crossing Grosvenor-square, and throwing at the windows of several large private houses as they passed, the mob reached North Audley-street, and here their work was as destructive as in South Audley-street.

Some of the shopkeepers, however, were prepared for them, and had put up their shutters.

THE MOB DISPERSES IN OXFORD STREET

Finally, the mob gradually dispersed in Oxford-street.

On Tuesday and Wednesday, fears of a renewed outbreak were entertained. and many shopkeepers at the West-End, and in the Strand, put up their shutters in the afternoon.

Trafalgar-square was guarded by a large force of police, and no further rioting was attempted.