Late on the evening of the 28th June 1887, 24-year Elizabeth Cass went out to purchase a pair of gloves from Jay’s millinery shop at 243 to 253 Regent Street in the West End of London.

Probably the last thing on her mind that evening, as she sauntered along Regent Street, was that she was about to find herself embroiled in a scandal that would shine a very bad light on the Metropolitan Police Force; would lead to a ferocious debate in Parliament; and which would cause a public outrage so great that even Queen Victoria herself would become involved in it.

MISS ELIZABETH CASS

Elizabeth Cass had grown up in Stockton-On-Tees, in the north-east of England where she had lived with her parents and where she had been employed by a number of persons as a dressmaker.

In May 1887 she had answered a newspaper advertisement placed by Mary Ann Bowman, a dressmaker of 19 Southampton Row, London and, having been given the job, she was engaged by that lady, who paid her 10s. a week as well as providing her board and lodging.

Before being employed by Mrs. Bowman she had stayed at Manor Park for three weeks with Mr. and Mrs. Tompkins, who had previously employed her in Middlesbrough.

She had, she later stated, not been in London before that time.

Prior to the 28th of June she had been in Regent-street with Mrs. Tompkins upon one afternoon, but had never been there alone and that was the only time she had ever been there.

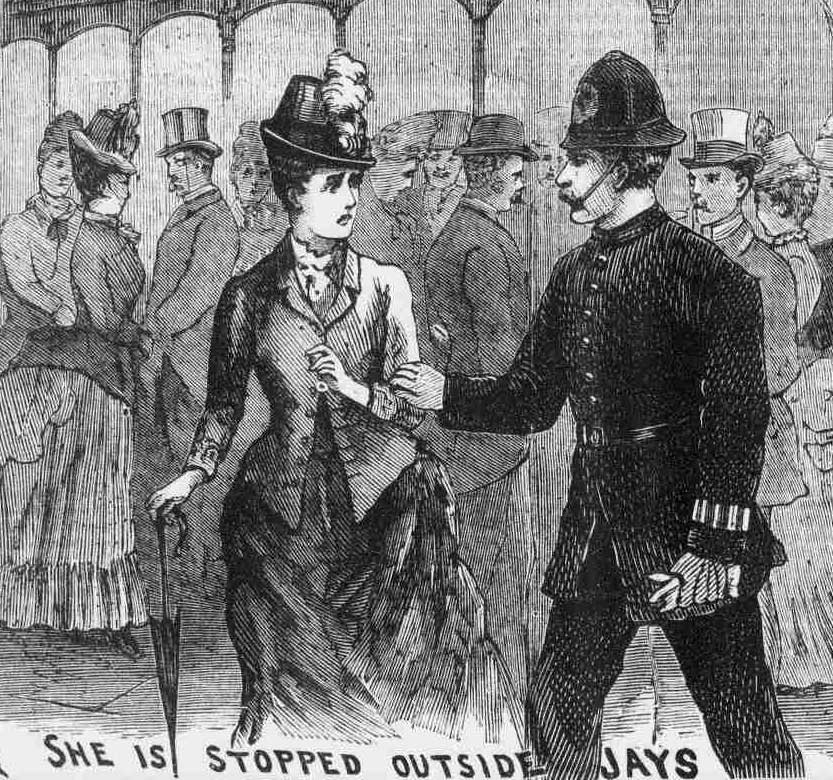

ARRESTED BY PC ENDACOTT

On the night of the 28th June 1887, she finished work at her usual time of around 8pm, and asked Madame Bowman if it would be alright if she went out. Permission was granted and she headed out at between 8.30pm and 9pm.

On leaving the house she cut through Bloomsbury Square and headed past the British Museum into Tottenham Court Road after which she turned along Oxford Street. She later stated that she had walked its first section, as far as Regent Circus, where she turned right and walked to the steps of the church of All Souls’ on Langham Place. She then turned and came back to Regent Circus, and then turned left and began retracing her route along Oxford Street.

She had, she said, been alone on the whole journey. She had spoken to no one, and no one had spoken to her.

Just after she had turned onto Oxford Street there was a little crowd at the corner, and she proceeded to push her way through it.

At this point a policeman – PC Bowden Endacott – came up, took hold of her arm, and said, “I want you.”

“What for?” she asked him.

“I have been watching you for some time.” was his reply.

Miss Cass told him, “You have made a mistake”, to which Endacott replied,”Oh no, I have not.”

He then asked her, “Who is that girl you were with?”

Miss Cass told him, “I was not with any girl,” but PC Endacott was insistent, “Oh yes you were, but she has slipped behind somewhere”

“You have made a mistake, I was not with any girl,” said Miss Cass – but again Endacott refused to believe her. “Yes you were; don’t tell lies; I wish I could have put my hand on her, as she is worse than you.”

Again Miss Cass insisted that he had made a mistake. “Oh no I haven’t,” was his emphatic reply.

Realising that arguing with the officer was futile, Miss Cass asked him where he was taking her and he told her to Tottenham Court Road Police-station

TAKEN TO THE POLICE STATION

Once more she told him that he had made a mistake, but he said that he had been watching her for a few weeks.

He then took her to Tottenham-court-road Police-station. As they walked he told her again that he wished he had got hold of the other girl.

She repeated that there was no other girl with her, and that he had made a mistake.

He then took hold of her arm, although she told him she would walk by herself. She later recalled that he told her several times “not to tell lies.”

At the police station she was placed in the dock and was charged with solicitation and prostitution by Endacott.

Acting Inspector Police Sergeant Comber asked Endacott what he had seen, to which the constable replied, “I saw here take hold of two or three gentlemen, and I heard her solicit for prostitution, and I took her into custody.” Comber then asked him if he knew her, to which Endacott replied, “Yes; I have known her as a prostitute walking Regent Street for some time.”

Turning to Miss Cass Comber asked, “You hear what the constable has said?” She didn’t reply. Indeed, Comber later recalled that she looked sullen and withdrawn.

At this point, Miss Cass moaned and fainted, whereupon she was given a chair and a glass of water.

Miss Cass was then taken to a cell, whereupon she asked not to be put in there.

“You must go in,” was Comber’s reply.

She pushed the door open, as the officer was closing it, and said, “You will send for Mrs. Bowman at once?”

At eleven o’clock that night she was taken out of the cell into the charge room, where she saw Mrs. Bowman, who asked her “what man she had been speaking to.”

She told Mrs. Bowman that she had not spoken to any men.

MRS BOWMAN’S RECOLLECTION

Mrs Bowman later recalled the events of the night in a statement that appeared in The Morning Post on 13th July 1887:-

“On the night of the 28th. Miss Cass said she wished to go out for the purpose of making a small purchase. That was at about a quarter to nine.

When Endacott came to the house at about half-past ten he said, “Miss Cass is your lodger ?” She replied that she did not take lodgers.

Endacott said she was charged with soliciting gentlemen in Regent-street, and that he had seen her there for the same purpose for many weeks.

She replied, “That is impossible, because she has not gone out.”

Endacott then said, “Well, if you want her you had better come and fetch her.”

Mrs Bowman then went to the station and saw Miss Cass, and became bail for her.”

MISS CASS’S COURT APPEARANCE

The next morning Miss Cass appeared before Stipendiary Magistrate Robert Milnes Newton at Great Marlborough Street Police Court.

Police Constable Endacott entered the dock to testify against her.

He claimed that he had seen her three times before in Regent Street, each time late at night and, on each occasion, she had been soliciting for prostitution.

Turning to the prisoner, Mr Newton asked Miss Cass what she had to say.

She replied that the policeman had made a mistake; and she insisted that she had not, as Endacott had asserted, been seen in the streets for weeks.

In fact, she continued, she had never been out alone before.

Mr. Newton then asked her what she did for a living, to which she replied that she was a dressmaker, and that she worked for Madame Bowman.

At this Mr Newton asked, “Who is Madame Bowman? Let her come forward.”

According to Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper:-

“She was not sworn. Mr. Newton asked what she knew of the Prisoner, and Madame Bowman replied that she was her forewoman, and that she was a respectable young woman.”

Mr. Newton observed that she had been out in Regent-street on the previous night, to which Madame Bowman replied, “Yes, but for no bad purpose.”

Newton, though, was having none of it.

“I say she was,” he insisted.

Visibly shocked by the Newton’s outburst, Madame Bowman asked, “I beg your pardon,” to which the irate Magistrate replied,”Don’t beg my pardon; stand down”

It was more than apparent that Mr Newton was far from convinced of Miss Cass’s innocence.

DON’T WALK ALONG REGENT STREET

Indeed, in his summing up, Mr Newton made it plain that, in his opinion, PC Endacott had been in the right and that Miss Cass had, in fact, gone out on the night of the 28th June 1887 for immoral purposes.

However, he opted to discharge her with a caution.

As Cass left the dock, Mr Newton could not resist the urge to impart a piece of magisterial advice as to how she should conduct herself in public in future:-

“Just take my advice: if you are a respectable girl, as you say you are, do not walk Regent Street and stop gentlemen at 10 o’clock at night. If you do you will either be fined or sent to prison after this caution I have given you.”

THE BLACK FLAG ON REGENT STREET

The Magistrate’s assertion – which effectively branded any woman who ventured along Regent Street after 10pm a prostitute – led to an outpouring of press indignation.

Commenting on Newton’s reprimand The Pall Mall Gazette, in its issue of the 7th July 1887, had this to say:-

“There exists no authority in the British Constitution whereby a police magistrate – for the time being – can set apart any quarter of the City as a preserve of prostitutes, but the authority exists in Marlborough-street police-court.

That authority is Mr. Newton.

However little he may have intended it, Mr. Newton has practically proclaimed Regent-street as a public lupanar [the Lupanar was the most famous brothel in Pompeii], by declaring that any young woman who speaks to a man in that famous thoroughfare after ten o’clock at night shall there and then, at the option of any police-constable, be arrested and afterwards fined or imprisoned.

That is, in effect, the result of his warning to Miss Cass, and it is not by any means the first time he has not merely pro-claimed Regent-street, but has given effect to his menace.

A correspondent signing himself “A Liberal” writes to us:-

I had occasion to be at Marlborough-street police-court some three years ago, with a cabman.

The night charges were brought in.

Several well-dressed females were charged in the same way as Miss Cass.

Some old looking foreigners looked capable of anything, while others, younger, protested their innocence.

“Were you in Regent-street after ten o’clock ?” said the magistrate. “Well, yes, sir, but I was —-.” “That’s enough,” said he: “fined or seven days.” “I am quite innocent,” said a young girl, excitedly, I remember. “But you were in Regent-street after ten, and you should not be,”said his worship: “fined, &c.”

The result is that at ten o’clock every night it is as if a Black Flag were hoisted, and the proclaimed district is practically set apart as a happy hunting ground for the debauchees of the town.

If the police may arrest and a magistrate imprison every woman in Regent-street after ten – then every woman, especially if she be young and pretty, is fair game for the fast man about town.”

MRS. BOWMAN COMPLAINS

The first hint the Metropolitan Police received that the case wasn’t going to slip quietly away came on the 30th June 1887, when Mrs Bowman sent a letter to Scotland Yard complaining about the police treatment of Miss Cass.

On the 1st of July 1887, Mr. Atherley-Jones – the Member of Parliament for North-Western Durham (who was also a barrister) – took up the case on Miss Cass’s behalf and raised the matter in the House of Commons, asking the Home Secretary, Henry Matthews, to order an enquiry.

Unsatisfied by what he perceived as Mathews’ flippant dismissal of the request, he succeeded in forcing a Parliamentary debate followed by a vote on the issue.

During that debate, one Member of the House, Mr Caine, even went so far as to accuse the Metropolitan Police of “being in the habit of levying blackmail from women in the streets”, and stated that “this was the root of the evil disclosed in the present case.”

When Atherley-Jones won the vote, Matthews had no choice but to order Sir Charles Warren, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, to carry out a full enquiry into the matter; and, by mid-July 1887, the name of Elizabeth Cass was the talk of newspapers countrywide, and Police Constable Endacott – who was suspended from duty on the 6th July 1887 – must have been ruing the day that he had decided to approach her on Regent Street.

In the next instalment we will cover the full enquiry into the case of Miss Cass.