On Tuesday 18th of November 1890, Mary Pearcey appeared at Marylebone Police Court, charged with the murder of Phoebe Hogg and her baby daughter.

Since her arrest, it had transpired that, although she was widely known as Mrs. Pearcey, she wasn’t, in fact, married and was, therefore Mary Ellen Wheeler.

It was under this name that she was tried, albeit the press continued to refer to her as Mrs. Pearcy, Piersey, or Pearsey – presumably as journalists were spelling her name phonetically as they heard it from the police or in court.

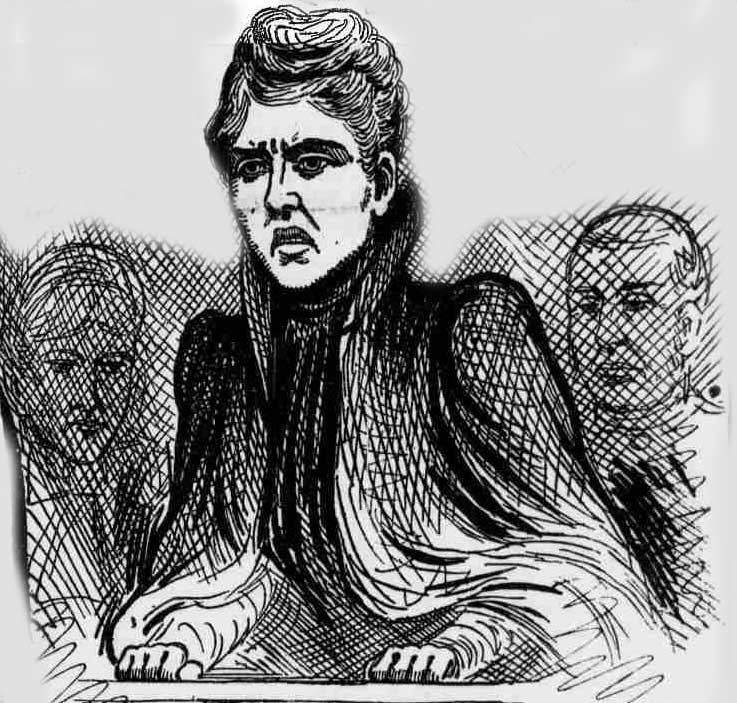

A DESCRIPTION OF THE ACCUSED

The following Sunday Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper provided its readers with a description of the accused and of her manner in court:-

“Mrs. Pearsey is a woman of about five feet six, neither slight nor stout. There is nothing of the murderess in her appearance; in fact, she is a mild, harmless looking woman. Her colouring is delicate and her hands are small and shapely.

But she has not a single good feature in her face. Her eyes are dark and bright, but of no size; her mouth is large and badly formed, and her chin is weak and retreating.

Mrs. Pearsey sat motionless in the dock at Marylebone on Tuesday, attired in a plain black cloak, a dark green hat, trimmed with dark green ribbon, and six-button black kid gloves. Never once did she move her head either to the right or the left; but for all that her mouth and her eyes were never at rest a minute. She was more on the alert than those who observed her casually imagined.

A thrill went through the court when she bent over the side of the dock to whisper to her solicitor; and at the close of the proceedings, when the prisoner was asked if she had anything to say, you could have heard a pin drop. Everybody was curious to hear her voice. It was a thin, weak voice, with no emotion in it.”

CHARLES BRITT’S STATEMENT

Several witnesses had come forward to give evidence that pointed to her having carried out the murder of Phoebe Hogg.

One was Charles Britt, who was described in the press as being a “little man of about 60 years of age,” who had been passing Mary Pearcey’s abode at 2 Priory-street at about 3. 30pm on the afternoon of October 24th 1890, when he noticed a woman, who was wearing a brownish hat and jacket, and who was holding a bassinette perambulator, and who was knocking at the door of number 2. As he passed, the door was opened, he believed, he said, by a lady.

CHARLOTTE PIDDINGTON’S STATEMENT

Next door neighbour Charlotte Piddington, who lived at number 3 Priory Street, said that she was very friendly with Mary Pearcey and that she had borrowed a wicker dress stand from her on the Tuesday prior to the murder.

By the day of the murder she had finished with it and wanted to return it.

So, according to her later testimony:-

“I looked over the wall – I put it over the fence in Mrs. Pearcey’s premises, and called “Mrs. Pearcey” five or six times – there is a wooden fence between the yards at the back, about three feet high – I got no answer – I was in the habit of so calling her when I wanted to attract her attention – she usually answered me – the time was about between three and four – before I put it over I heard a smashing of glass – the sound seemed to come from downstairs – I was upstairs against the landing window on the first floor – when I had put the stand over I heard another smashing of glass as I was going in – I went back into the house, and stopped upstairs till about two or three minutes to four, when I came down – I also heard a child scream as I was putting the stand over the wall – it was a sound like a child in pain, or being hurt, or something – I came out into the garden again to fetch the clothes in because it was raining – the stand had gone – I did not look at the clock.”

SARAH BUTLER’S STATEMENT

Sarah Butler, who, with her husband, lived on the second floor of 2 Priory Street – and who stated that she knew the the murdered woman’s husband Frank Hogg as “Mr Pearcey” – had come home at around 6pm on the evening of Friday 24th of October 1890.

On entering the passage she later recalled:-

“I noticed it was dark – usually a light was in the passage – Mrs. Pearcey attended to it – I knocked myself against a bassinette that was close to the hall door – on the right as you come in. I saw Mrs. Pearcey against her front sitting-room door – I could not see whether there was a light in the room – she said, “Mind” – I said, “All right, I can feel what it is” – I passed it – in going towards the stairs I passed Mrs. Pearcey – she was dressed – she had a hat on – I went upstairs – shortly afterwards I heard my husband come in – I had only got up the first flight of stairs – in about ten minutes I came down alone – I went along the passage to go out – the bassinette had gone – that was about ten minutes past six – I returned almost directly – I went out again – I came home the last time about 10.15 – I saw nothing more of the prisoner that night.

The next morning, Saturday, I came down about eight – I went through the back door – I noticed a good bit of burnt paper on the mat – in the yard I noticed two panes of the kitchen window broken – I went into the little wash-house at the end of the passage – the floor was swamped with water – I saw two zinc baths there, with a black apron over them – the apron appeared to be wet – it was spread out – I went back into the house – about 10.30 I came down again – I went into the wash-house – I saw a pair of long lace-curtains with some blood on them – I had seen them in the kitchen two or three days past…”

ELIZABETH ROGERS’S STATEMENT

Elizabeth Rogers, who lived at 7, Priory Street with her husband William, stated that she knew the prisoner very well on account of the fact she had done her mangling for the previous six months.

A little after 6pm, on Friday 24th of October 1890, she had turned out of Bonny Street into Priory Place and was about to pass under the railway arch when she saw Mary Pearcey pushing a bassinette perambulator in the middle of the road.

She later recalled:-

“It was very heavily loaded and was covered over with some black stuff. It was higher at the head than at the handles – I was coming in the direction of her house – she was going the other way – when she saw me she dropped her head over the handles, and she had a difficulty in pushing it up the hill – the road is narrow at that spot – I looked round – she turned to the left – that would lead her into the Prince of Wales Road.

I had seen her once or twice walking in Priory Place the week before this – she wore a green hat with green ribbon round, and a dust cloak – on this night she had a light ulster with buttons – I could not see a dark brown dress and black jacket; the ulster was buttoned – the hat looked green, not blue – the place is dark – I was at the kerbstone – nothing was said by either of us…”

ANNIE GARDINER’S TESTIMONY

Shortly after passing Elizabeth Rogers, Mary Pearcey had been seen, wheeling her cumbersome load, by another crucial witness, Mrs Annie Gardiner.

The Illustrated Police News reported what she said she had seen in its edition of November 15th 1890:-

“On Friday evening I left my house, 13 Crogsland-road, which leads into the Prince of Wales-road, near the house of the deceased woman, to go shopping. I had only come from the country at three o’clock in the afternoon. This was about half-past six.

As I crossed over Crogsland-road into the Prince of Wales-road I saw a person coming along with a perambulator. I thought I knew her, and, of course, I looked right into her face to see if I knew her. I found that she was not the woman I took her to be.

I turned completely round, and stood perfectly still, looking after her, and said to a little girl I had with me, “Oh, good gracious – what a load that woman has got on her perambulator! I suppose it’s someone moving.”

It looked to me as if someone was moving, and had packed as much on the perambulator as they could get on, and covered it with a black shawl.

There was nothing smooth about it, and it looked as if things had been piled on the top as thickly as they could, and then tucked the shawl down to keep the things from falling off. The things did not look like tumbling off.

She was going towards Haverstock-hill, and I watched her past the row of houses in which the deceased lived.

When I first saw the woman she was about a yard, not more, round the corner from Crogsland-road, and in the Prince of Wales-road.

She was coming from the direction of the Castle-road. She was in the road about a foot from the pavement and I stood on the kerb. She didn’t look in my face, but she must have heard my voice and what I said to the little girl, but she didn’t look round.

She was making as much haste as she could with her load. She had a difficulty in pushing it. In fact, I thought what a shame it was to load a perambulator so heavily. I am sure I looked into her face quite close from the kerb, because I was able to distinguish that it was not the person I took her to be.

I was taken to the police-court last Tuesday, and taken into a room full of men and women. I was asked to pick the woman out, which I did. I remembered her height, face, and figure exactly, and I identified her as the woman I saw wheeling the perambulator. When I identified her I saw that she had a green hat on, but I had described it as a black hat, and of course a green hat would look like a black one at night.”

SARAH SAWHILL’S STATEMENT

Sarah Sawhill, a female searcher at Kentish-town police-station, had told an earlier court hearing of an exchange she had had with the accused on the 25th of October 1890.

According to Sawhill, whilst she was carrying out the search Pearcey had told her:-

“I met Mrs. Hogg on Wednesday afternoon, accidentally, in Kentish-town-road. She passed me by and took no notice of me.

On the Thursday I wrote a note to Mrs. Hogg and gave it to a boy to take to her….to invite Mrs. Hogg to my place on Friday afternoon to tea, as I would be at home that afternoon….I sent the note by a boy, who was to wait for an answer.”

Pearcey then went on to say that Mrs Hogg had arrived at her place at “…between four and a quarter past. As we were having tea Mrs. Hogg made a remark that I did not like. One word brought up another.”

At this point Pearcey, realising that she was incriminating herself, had stopped and observed, “Perhaps I had better not say anymore.”

MARTHA STYLES’S INQUEST TESTIMONY

Martha Styles, the sister of Phoebe Hogg, told the inquest into her sister’s death that the last time she had seen Phoebe alive was on the 23rd of October when the deceased had come to meet her off the train at Finchley Road Station.

On that occasion the deceased showed her a note that, she said, had been delivered that day by a boy and which, she said, she believed had come from Mrs. Pearcey.

They were both surprised by this because Phoebe had not seen Mary Pearcey since the February of that year.

The note, so Martha Styles told the inquest, was written on an odd piece of white paper, and was written in pencil.

There was no date or address on it.

It read:-

“Dearest, Come round this afternoon and bring your (or our) little darling. Do not fail.”

Martha said that she had seen Pearcey’s handwriting and was certain it had come from her.

MRS HOGG’S SUSPICIONS

In fact, her sister had received a similar note, three weeks before asking her to go and see the writer (although there was no signature) at some public house.

When Phoebe Hogg arrived at the location, Mary Pearcey crossed the road to see her and asked her to go on a trip to the seaside with her. Mrs Hogg had told Pearcey that she would decide whether she would go or not at a later date and would let her know her decision.

According to Martha Styles’s inquest testimony, her deceased sister had told her that the idea of the trip was that they could look over an empty house – she thought in Southend. She was to leave her baby with Mrs Pearcey’s nurse.

Phoebe, she testified, had told her, “If she wants me to go she will have to wait a very long time.”

Later, her sister had told her that “If I had gone to Southend no-one would have thought of looking for me down there in an empty house.”

She ended her evidence by stating that her deceased sister had entertained grave suspicions of Mary Pearcey’s motives.

WILLIAM HOLMES’S TESTIMONY

The boy who had delivered the note to Phoebe Hogg, on Mrs. Pearcey’s behalf ,was 12-year-old William Henry Holmes, who lived at 138 Prince of Wales Road.

He later related how, on the morning of Friday 24th of October, at about 11am, his mother had sent him to the shop.

As he was returning home he met Mary Pearcey who asked him if he would deliver a note for her. He informed her that he would have to take the things in first and, having handed them to his mother, he came out and saw Pearcey waiting for him on the opposite side of the road.

Crossing to her, she asked him to take a note to 141, Prince of Wales Road where he was to ring the top bell.

He later recalled:-

“She gave me a penny and the note and said I was to be sure to give it to Mrs. F. Hogg. I went to 141 – it was about one hundred yards – I rang the top bell – I gave a woman who opened the door the note – I went back – I saw the prisoner again in the Crogsland Road, and she beckoned me towards her – I went; she asked me if I gave it to a tall elderly person with a fringe – I did not know, so I said, “Yes” – I mean I did not know what she meant – I had given the note to a tall woman – she said, “All right, thank you,” and walked away…”

AN INTERVIEW WITH ELIZABETH STYLES

It appears that Martha Styles wasn’t the only relative of Phoebe Hogg, to whom the murdered woman had confided in concerning her suspicions of Mary Pearcey.

On the 9th of November 1890, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper had carried an interview that Elizabeth Styles, the dead woman’s niece, had given to the Central News Agency:-

“A representative of the Central News the other day obtained an interview with Miss Elizabeth Styles, a niece of the murdered woman.

Being asked as to the relations which existed between Mrs. Hogg and her husband, Miss Styles said they were distinctly unhappy.

It was certainly not true that the deceased knew Mrs. Pearcey before marriage.

“I knew,” continued Miss Styles, “that my aunt only became acquainted with Mrs. Pearcey through the Hoggs’ connection.”

How do you think she was induced to visit Mrs. Pearsey after she said that she would not?

“That I cannot tell; there must have been some very strong inducement in the letter which she received on Friday morning.

I am sure that it had been planned to murder her on the Thursday.

I met my aunt that afternoon, and we went to Finchley-road station to meet my other aunt, Miss Styles, who was coming from Rickmansworth.

She showed us Mrs. Pearcey’s letter, and she said that Mrs. Pearcey would have to wait for a long time if she waited for a visit from her.”

Are you sure that your aunt suspected her husband’s visits to Mrs. Pearcey?

“I am certain of it. My aunt often spoke to me about it. When my aunt called at Mrs., Pearcey’s about a fortnight ago, to say that she could not go to Southend, she said, after a while, “Well, I must go, or-Frank will be home.” Mrs. Pearcey immediately said, ‘”Oh no he won’t be home before eight o’clock.””

Do you think your aunt was in actual fear of Mrs. Pearcey?

“I am sure she was. She never-liked Mrs. Pearcey, and I never did. She avoided me; I really think she imagined I could see through her. I know my aunt was afraid of her, for when she spoke to us about the Southend affair she said, “No fear of me going to Southend. Why, I might be thrown over the cliffs, and none of you would know anything about it here.””

Will you tell me what was your first intimation of the terrible occurrence?

“It was on Saturday morning that I first heard of it. Somebody had told me of a murder in Crossfield-road, but I did not take any interest in it.

But when an inspector called upon me in Albion-road, and began to ask me questions, I said, “Oh, surely it can’t be her! ” The inspector said, “Don’t be upset; it may not be her.”

“Well,” I said, “if it is so, I know who did it.”

When the inspector asked me who, I said, “Mrs. Pearcey.”

That was what made them go and search her house – Inspector Miller said so.”

TESTING THE PERAMBULATOR

Lloyd’s Weekly News also reported how Inspector Banister had revealed that the police had gone to great lengths to establish whether Mary Pearcey could have used the perambulator to remove the bodies of Mrs. Hogg and her infant daughter from the scene of the crime:-

“I tested the perambulator, to see if it would bear the weight of a fully grown body, by getting into it myself, being covered over and wheeled about in it.

I tested and found that such a perambulator could be wheeled with perfect ease from the street through the passage and into the kitchen….”

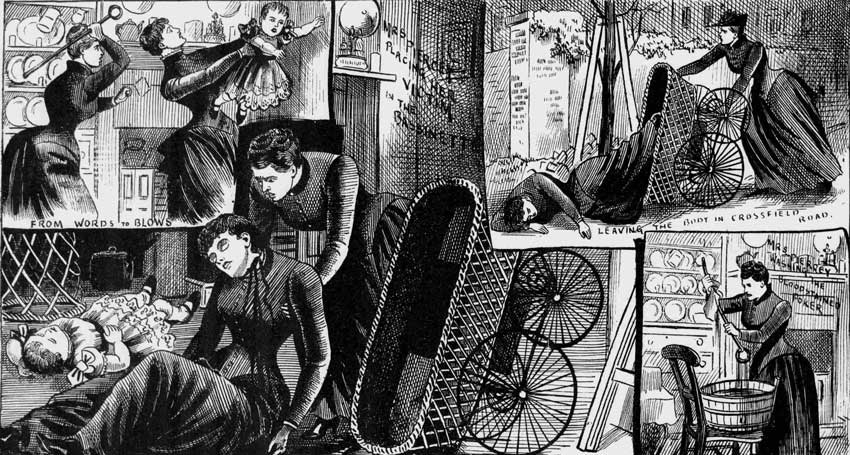

THE MURDER OF PHOEBE HOGG

The consensus amongst the detectives working on the case was that Mary Pearcey, by way of a note delivered by the boy Holmes, had lured Phoebe Hogg to her rooms at 2 Priory Street on the afternoon of Friday 24th of October 1890.

In the course of a conversation, something may have been said that sent Mary into a fit of rage in the course of which she seized a poker and struck Phoebe a blow which had knocked her unconscious.

She had then cut her throat and loaded her body into the perambulator, placing Phoebe on top of her daughter, which had suffocated the infant.

Having done so, she had covered over the gruesome cargo, and had then wheeled it off through the streets – where she had been seen by the aforementioned witnesses – her intention being to dump the bodies on wasteland.

However, the cumbersome burden proved too much for the perambulator and it had collapsed, causing the body to fall out at the spot where it was found in Crossfield Road.

She had then continued to Hamilton Terrace, where she had abandoned the vehicle before taking the baby to the wasteland and leaving her where her body was found.

Certainly the Jury at the Coroner’s inquests were in no doubt that Mary Pearcey had murdered the mother and baby and they returned a verdict of wilful murder, citing Mary Pearcey as the perpetrator.

At the Marylebone Police Court hearing, the presiding magistrate committed her for trial at the Old Bailey.

MARY PEARCEY’S OLD BAILEY TRIAL

The trial of Mary Pearcey for the murder of Phoebe Hogg and her daughter Phoebe Hogg, commenced at the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey) on Monday the 1st of December 1890.

On the 7th of December, 1890, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported on the opening of the trial:-

“The trial of Mrs. Pearcey, for what are known as the Hampstead murders, drew a large and excited crowd to the Old Bailey on Monday.

Some time before the opening of the Court the Prisoner was conveyed from Holloway to Newgate in a cab, in charge of a male and female warder…When the unhappy woman stepped up into the dock and found herself suddenly in the midst of a prying crowd, every eye turned upon her, and confronted by the imposing array of the judgement-seat, she visibly quailed.

Nevertheless, she stepped composedly forward, looking very much improved since her last appearance at Marylebone.

Her black crepe-trimmed cape had given place to a brown cloak and the hat had been discarded. She wore her brown hair rolled tastefully about her shapely head.

THE DEFENCE, PROSECUTION AND JURY

Mr. Forrest Fulton and Mr. C. F. Gill appeared to conduct the prosecution on behalf of the Crown, the prisoner being defended by Mr. Arthur Hutton. Mr. J. P. Grain held a watching brief on behalf of Mr. Frank Hogg, the husband of the deceased.

During the process of empannelling the jury, a juror asked to be excused from serving, on the ground that he entertained doubts as to the legality of capital punishment.

The Judge: If you really have any doubt on the subject I think you ought to be excused. The juryman then left the box and another was sworn in his place.

The case is exceptional, as several well-known City men are said to have actually asked to be summoned on the jury for this trial.

The prisoner remained standing while she was formally charged with the two-fold murder, and to each indictment she replied in a firm, soft voice, “Not guilty”

Then she sat down in a chair placed in the centre of the large dock, crossed her hands in her lap, threw her head well back, and sat all but motionless throughout the proceedings.”

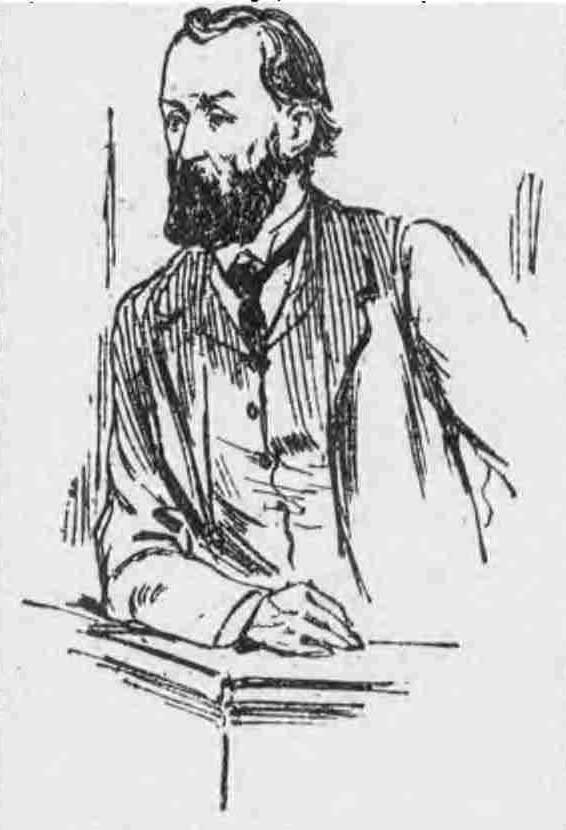

FRANK HOGG IN THE WITNESS BOX

One of the early witnesses to give evidence was the bereaved husband, Frank Hogg, who provided the court with the information on how he came to meet his wife and on his relationship with the defendant.

He and Phoebe, he stated, had been married since November 1888, although he admitted that he had been “familiar” with her prior to their marriage and, as a result, their daughter, Phoebe Hanslope, had been born on the 11th of April 1889.

HIS MEETING WITH MARY PEARCEY

He had met the accused, he said, around 1886, when she was living with her husband, Mr Pearcey, in Bayham Street, Camden Town.

As it had, by this time, been revealed that the accused wasn’t actually married to Mr Pearcey, Frank Hogg clarified that he had “always believed that he was her husband, she went by the name of Mrs. Pearcey.”

When they met, he was, he said, managing a provision business that belonged to his mother at 87, King Street, Camden Town, and he continued to manage that business up to the 22nd of March, 1888, when he left it to become a furniture mover, sometimes for his brother, and for some time at Shoolbred’s.

As far as he could remember, Mary Pearcey had moved from Bayham Street to 2, Priory Street in September or October 1888, and he had called on her, only once or twice he insisted, although he was in the habit of receiving letters from her.

HIS AFFAIR WITH THE ACCUSED

He confessed that he had had a latchkey to 2, Priory Street for about the last twelve months, which Mary Pearcey had given him so that he could “go in” when he liked and “have immoral intercourse with her – that intercourse first took place after my marriage; never before – I believe it was at the Christmas time, 1888, the Christmas following my marriage – it continued up to 24th October this year.”

CHRISTMAS WITH HIS WIFE AND LOVER

He then went on to give details of the bizarre circumstances under which his wife had first become acquainted with the woman now accused of her murder:-

“…my wife was not acquainted with the prisoner till December, 1889 – the prisoner sent an invitation through me, verbally, to ask her to spend Christmas Day with her – I carried the message – my wife was not aware at that time of the relations between the prisoner and myself – she accompanied me on Christmas Day last to 2, Priory Street, and I introduced her to the prisoner – we stopped there that night and the day following, Boxing Day – I and my wife occupied one bed, and the prisoner another – after that the prisoner was in the habit of coming to visit my wife at 141, Prince of Wales Road, from time to time, as a friend, with the child – in January, 1890, my wife was seized with illness – the prisoner came to 141 and offered to nurse my wife in her illness, and take care of the child; we kept no servant – my wife could not keep about; she was sometimes in one room, and sometimes in another – she was not able to attend to her domestic duties – she continued in that condition for about a fortnight or three weeks as far as I recollect – during that time the prisoner was not an inmate of 141; she came in the morning, and went away at night; for the first two or three days she stayed the night, but afterwards she came in the morning, and went away in the evening…”

DR THOMAS BOND’S TESTIMONY

The various witnesses who had previously testified at the inquest and Marylebone Police court – and whose evidence can be read higher up this page – were then called to testify.

One of the final witnesses to be called was Dr Thomas Bond who had examined the body of Phoebe Hogg at the mortuary on the morning of Saturday the 25th of October 1890.

He told the court what he had found:-

“The scalp was very much broken at the back, and the bones of the skull were fractured, and some of the fragments penetrated the brain. The throat was cut, and the spinal column was divided, so that the head was adherent to the body only by the muscles at the back of the neck and by some skin. Those cuts had been made during life, or immediately after death – the skin and muscles were much retracted from the cut; that would indicate that the cut had been made either during life, or very soon afterwards, while the body was still warm.

There was a bruise on the forehead, and a cut on the forehead, and I also found on the right forearm, in front, a large ragged cut, which appeared to have been done by glass.

I formed the opinion that the scalp had been first injured there was a large quantity of matted blood all over the hair, and great extravasation of blood under the scalp.

In my opinion the cause of death was the fracture of the skull and the cut throat – the fracture of the skull alone was enough to cause death, but I do not think it would have caused death immediately. The poker produced is such an instrument as might have caused the fracture.

There might or might not be convulsions as the result of such a blow – I think there were convulsions, because the motions and faeces had passed on to the clothes; that would ordinarily occur in convulsions; I did not see that, I was told by one of the doctors in attendance that that had occurred.

The cuts on the throat must have been made by more than an ordinarily sharp knife.

There was one fracture on the skull cap which was oblong in shape, and when I compared it with the round part of the handle of this poker, it corresponded as nearly as I should expect a fracture through a bone to correspond.

On the 26th October I went to 2, Priory Street, and there examined the back kitchen.

I saw where the panes of glass were broken; they were apparently broken from the inside; the fragments had all fallen on the outside – there were splashes of blood on the panes that remained in the window. I examined the glass that had fallen outside I found one spot on a fragment which had fallen outside; but I found two spots and a little streak on the broken glass which remained in the pane that was outside.

The ceiling and walls of the kitchen were splashed with blood, and the different articles in the kitchen had spots of blood on them; it was not such blood as would be produced by spurting from an artery; they were round in spots, similar in shape to splashes of mud that you see on walls or windows, such as might be caused by striking with some heavy instrument…”

MARY PEARCEY’S DEFENCE

The evidence against Mary Pearcey was, to say the least, quite overwhelming; and the fact that no witnesses were called in her defence effectively sealed her fate in many peoples eyes.

Mr Arthur Hutton, defending her, argued that most of the prosecution’s evidence was circumstantial and, furthermore, he argued,”evidence which it would be most dangerous to accept as conclusive.”

He went on to point out that:- “as the jury would have noticed, the prisoner, had she been guilty, might easily have escaped, but had not done so.”

THE JUDGE’S SUMMING UP

Notwithstanding her defending barristers bold attempts to create reasonable doubt in the mind of the jurors, the judge, Mr Justice Denman, in his summing up, pointed out that:-

“As regards the case being one of circumstantial evidence, it was not to be expected that there would be an eye witness in the case of a premeditated and deliberate murder.”

The judge made not attempt to hide the contempt he felt for Frank Hogg:-

“It must be said,” the judge told the jury, “that no man ever gave himself a viler or more loathsome character…they could scarcely have a witness who they should watch with closer care or suspicion than a man who came before them to tell them such a shameless story of his relations with the prisoner and other women, including his own wife…”

He went on to state that:-

“The finding of the button was an important thing because it tallied exactly with all the buttons on the dress which the deceased woman wore… The knife and poker that the police found were fully capable of performing the dreadful things which had been perpetrated..the only thing that you have to decide is whether you are satisfied beyond reasonable doubt that the prisoner did, on the 24th of October, between the hours of ten minutes past three o’clock and ten minutes past six o’clock, either by herself, or with someone else…get rid of the deceased woman by blows on her head with the poker, and by cutting her throat with some sharp instrument. If you entertain no reasonable doubt about the matter, you ought to convict the prisoner; but if you entertain any doubt as to whether she was, either by herself, or with others, instrumental in the murder, you ought to give her the benefit of the doubt.”

In his summing up the judge also made special mention of the fact that Mary Peacrey had whistled whilst the police were searching her house the day after the murder and advised them that this showed her utter lack of remorse over what had occurred.

The jury then retired to consider their verdict.

AWAITING THE VERDICT

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, on Sunday the 7th December 1890, recalled the atmosphere in court as the jury left the room:-

“The prisoner meanwhile sat quietly, but, when touched on the shoulder, rose and walked firmly dawn the stairs leading from the dock.

The Judge, who, it was noticed, had the black cap beside him on the bench, kept his seat for some quarter of an hour, as though expecting the speedy return of the jury.

As there was no sign of this, his lordship, the presiding alderman (who sits under the sword of Justice), and the two sheriffs then left.

The court instantly broke into a babel of conversation.

No one seemed to entertain any doubt as to the verdict; though some little surprise was manifested to find the clock strike two without its being given.

Momentary excitement was caused by a communication being sent from the jury-room to the judge and a reply-returned. But nothing transpired as to its nature.

Shortly before a quarter past two there came the cry of “Order,” and the peculiar hush which settles down upon a criminal court when the final scene of a great trial is about to be reached.

The Judge returned to the bench, the jury moved through a crowd of spectators to their box, and the unhappy prisoner was brought back for the last. time.

At the top of the stairs she hesitated for a moment as if uncertain what to do.

Her bearing was wonderfully calm, the only display of emotion being a tremor of the lower lip.

She was gently conducted to the front of the dock; a female attendant standing close to her right, a male warder at her left, and another immediately behind her. But she stood in full view of the court, which was now densely crowded to the very doors, without any need of assistance.”

FOUND GUILTY

The article continued:-

“Gentlemen of the jury, have you agreed on your verdict? asked the Clerk of Arraigns.

“We have,” replied the Foreman.

“Do you find the prisoner at the bar guilty or not guilty?

There was a touch of deep emotion in the Foreman’s voice as, amid deep silence, he answered – “GUILTY.”

The prisoner never moved a muscle, but looked straight before her with the same inflexible look which she had borne throughout.”

HAD SHE ANYTHING TO SAY

The prisoner was then asked if she had anything to say why sentence should not be passed on her?

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported that:-

“Though she showed no sign of breaking down, even at this awful moment, the prisoner’s tongue seemed to cleave to the roof of her mouth, as she murmured, “I am innocent of this charge.”

MARY PEARCEY SENTENCED TO DEATH

The judge then donned the black cap and proceeded to pass sentence on the prisoner:-

“You have been found guilty after a most patient trial, and after a most powerful and able defence, and I must say that I feel it to be absolutely impossible to conceive that the death of Phoebe Hogg would have taken place without your having been an active instrument towards that death.

It is a terrible case. I don’t wish to add to the pangs which you must feel by saying much to you.

I do say, however, that I think it is one of many instances which have come before me, even at this very Session, of the terrible results of persons giving way to prurient and indecent lust.

You have become a person of so little moral sense that eventually you have been an instrument, and a willing instrument, of taking away the life of a woman whose only offence was that she was married to a man upon whom you had set your unholy passion.

Now, I cannot hold out to you any hope whatever.

Within a very short time you will have ceased to live as am inmate of this, our world.

You will have a certain time to prepare yourself for death. God grant that you will use that time for the best, and that you will employ the short time that you have on earth in preparing yourself for another world.

I pass upon you the sentence of the law, that you be taken from here to the place from whence you came and thence to the place of execution, there to be hanged by the neck until you are dead, and your body to be afterwards buried within the precincts of the place where you are executed; and may the Lord have mercy upon your soul.”

HER REACTION TO THE SENTENCE

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reported on her reaction to her sentence in its 7th of December issue:-

“Throughout the delivery of sentence the prisoner stood firm and erect, but the frequent movement of the “tell-tale hands” indicated suppressed anxiety.

At the reference to her removal from “this, our world”, tears forced themselves to her eyes and moistened her cheeks.

She met the next ordeal, however, with such undiminished firmness as to extort from one of the detectives engaged in the case the remark that, “she was the most remarkable criminal he had ever seen or read of.”

In the usual form provided for females the Clerk asked the prisoner if she had anything to urge why the sentence of death should not be carried out?

The reply was awaited amid intense silence, but the unhappy creature seemed doubtful as to what was expected of her.

After a momentary but painful pause, the aged warder on her left whispered to his female companion, “You’d better tell her.”

She at once made the inquiry as to her condition, which the prisoner met with a shake of the head.

At this instant a portion of the question was repeated, by the Clerk, and Mrs. Pearcey answered in a clear, steady voice, “Only that I am innocent of this crime, sir.”

Then she turned, round and walked quietly, and without assistance, down from the dock.”

HER EXECUTION

Mary Pearcey was executed at Newgate Prison on the 23rd of December 1890.

Right up until the moment the noose was placed around her neck, she insisted that she was innocent of the crime; although, when the chaplain asked her, as she mounted the scaffold,”Do you admit the justice of your sentence? ” she gave the enigmatic response “Yes; but the greater part of the evidence was false.”

RELATED ARTICLES

The Murder of Mrs Phoebe Hogg, 23rd October 1890.

Shameful Scenes At The Funeral Of Phoebe Hogg.

FURTHER INFORMATION

Read the full Old Bailey transcript of the Mary Pearcey Old Bailey Trial.