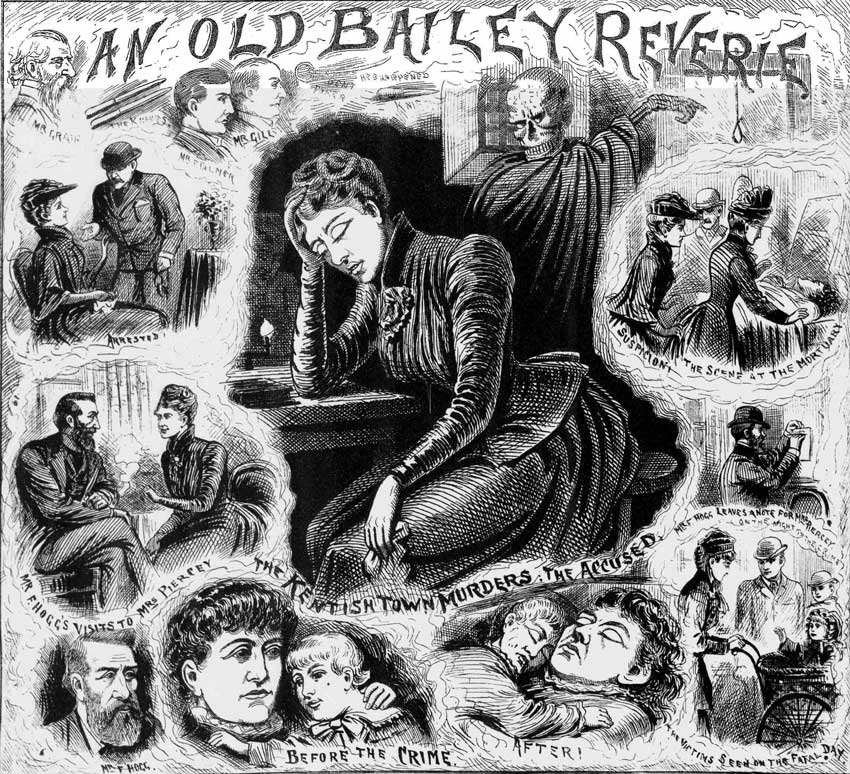

Following the “guilty” verdict at her trial, for the murder of Phoebe Hogg and her infant daughter, several attempts were made to commute Mary Pearcey’s death sense to one of imprisonment.

She was also urged to claim insanity, a request she steadfastly refused.

The newspapers were convinced that she must be guilt-ridden over her foul crime and that memories of it must be haunting her as she languished in her prison cell, despite the fact that she had, as far as anyone could tell, shown no remorse, or, for that matter, acknowledgement of the crime.

THE EXECUTION OF MARY PEARCEY

Accordingly, her execution took place at Newgate Prison on the 23rd of December 1890.

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper recounted the days leading up to and the immediate aftermath of her execution in its’ edition of the 28th of December 1890.

“The official intimation from the Home Secretary that he could not interfere with the course of law in the case of Mrs. Pearcey was not made known to the convict until the chaplain’s visit on Sunday, when he informed her that all appeals for human mercy were at an end.

The prisoner gave no sign of anxiety or regret, and merely turned in her seat and passed her hand across her brow, remarking as she had so often done before, “I am innocent of the murder.”

The Rev. Mr. Duffield spent a great portion of the day in the condemned cell in quiet, earnest conversation with the woman, who appeared quite reconciled to her fate.

TRINKETS DISTRIBUTED

Shortly after 10 on Monday morning Freke Palmer [Mary Pearcey’s solicitor] had a parting interview with the prisoner.

As the day was so cold, their conversation took place not in the ordinary visiting “cage,” but in the chief warder’s room, which is well warmed and lighted.

She entered with a firm step and a certain amount of cheerfulness, remarking on the disagreeable weather.

Her first desire was to ask Mr. Palmer to distribute certain of her articles and trinkets, all trinkets of very small value, among her relatives and friends – a ring to her mother and a testament to her sister.

A STRANGE ADVERT

Mrs. Pearsey next requested that Mr. Palmer should cause an advertisement to be inserted in the Madrid papers dressed to certain initials, with these words, “Have not betrayed.”

[The full advert, which has never been explained, read – “TO M.E.C.P. – Last wish of M.E.W. Have not betrayed.”]

Surprised at this commission, Mr. Palmer asked whether it had to do with the case.

“Never mind,” said she.

He then asked, “Do you admit the justice of the sentence?”

“No,” was the reply, “I do not. I know nothing about the crime.”

“But,” it was urged, “even if you did it in a trance you must have some idea or shadowy recollection of the matter?”

“I know nothing about it,” she repeated.

“Under those circumstances let me ask whether you are satisfied with what we have done for your defence and the efforts we have since made on your behalf.”

“I am perfectly satisfied,” she responded, “I don’t think any more could have been done.”

“If you have any facts to reveal, and will let me know them, even at this late hour, I will lay them before the Home Secretary, in the

hope of obtaining mercy.”

“I have nothing more to say; don’t forget about those things. Good-bye.”

And she went again across the yard to her cell.

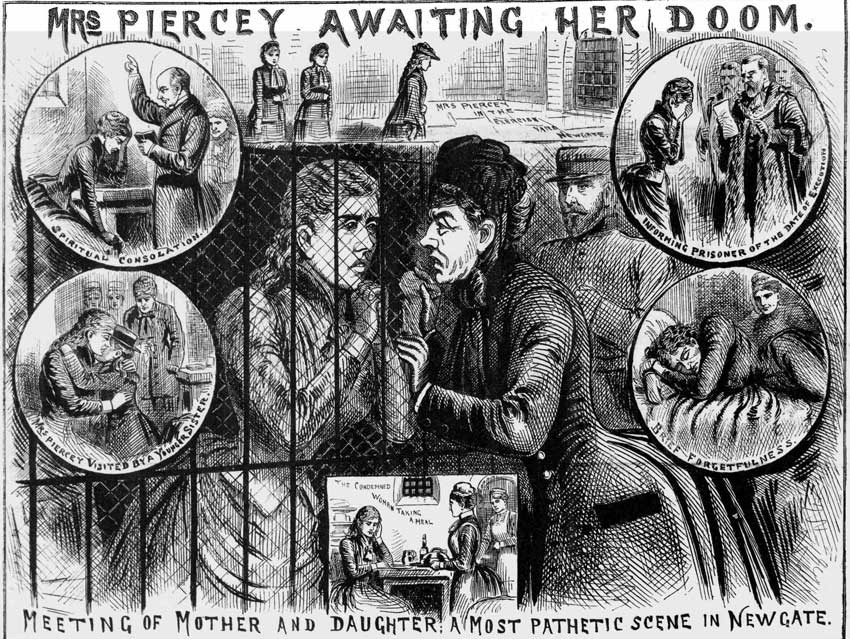

THE MOTHER’S FAREWELL

Mrs. Wheeler [Mary Pearcey’s mother] rose at seven on Monday morning, and after getting a cup of tea, started, accompanied by her youngest daughter, shortly after eight, so as to be at the gate of Newgate at 10 and have all the time they could with the ill-fated girl.

The fog was so dense that it was with great difficulty they could grope their way along.

After travelling some distance in a train they changed to an omnibus, but unfortunately got into one which carried them up Bishopsgate-street.

This mishap caused considerable delay, and it was 20 minutes past 11 o’clock before they reached Newgate.

The convict had been growing impatient, and the mother and daughter were told they could only have a final interview of 40 minutes, instead of the two hours allotted to them.

Mrs. Wheeler and her youngest daughter were allowed to see the convict in the chaplain’s room.

She received them very affectionately, and after embracing and kissing them both she took them each by the hand and sat down between them, laying her head all the time on her mother’s breast.

SOME TIME IN SILENT GRIEF

In subsequently describing the interview, the mother said:- “After we had spent some time in silent grief, Nelly said to me, “Well, mother, my time is very near now when I shall see you no more. But I feel resigned now. I am trusting in a merciful Saviour, and I feel that God will forgive me all my sins, and that I shall go to heaven, and that I shall meet my father and my two little sisters there before you. Yes, I shall see them first.”

I then said to her, “Well, Nelly, if you are guilty I hope you will confess.”

She then said in a most emphatic manner, “Mother, I am not guilty; I am innocent. You do not think I am guilty, do you?”

I said, “No, child, I do not think you are guilty if you say you are not at such a solemn time as this.”

THEY WANTED ME TO PLEAD INSANITY

Then she said, “Mother, they wanted me to plead insanity, but I would not have that plea at all. I know I am not insane. I am no more insane than any of them, and I was not going to be sent into the presence of my Maker with a lie in my mouth.

Besides, if my life had been spared on that plea I should only have been sent among a lot of convicts and criminal lunatics, and I might have grown as wicked as the worst of them, and have had a long life of misery.

No, mother, I am innocent of the real murder, but rather than be shut up with a lot of convicts I would sooner die than live.”

LOVE AND KIND MESSAGES

Then we talked about business arrangements.

She had been in the habit of allowing me a little money every week to pay the rent of my room, and she seemed very much concerned how I should get on without her.

She sent her love and kind messages to all her relations and friends, and expressed a hope that they would not think her guilty of the terrible crime imputed to her.

Then she asked me to be kind to her sister and brothers, and I said I would.

Next she took her sister’s hands, put her arms around her neck, and said, “And now dear, you will be a good girl, won’t you, and not fall into any temptation?” Her sister replied that she would.

Then we kissed and embraced each other, and taking a last farewell, left the gaol, getting back home again, I scarcely know how.”

THE WISH TO SEE HOGG

At the convict’s particular and reiterated request permission was given to the man Frank Hogg [her lover and the husband and father of the victims] to visit her between two and four on Monday afternoon, and it was quite evident that she had built upon seeing him once more.

As the time passed on, and he did not come, she grew somewhat nervous and impatient, and when it was evident that she would be doomed to disappointment, a terrible fit of dejection seized her.

She lay on her bed with her bands over her face for some time sobbing, but not speaking.

When this was over, and she rose again, her face was calm, her voice had recovered its quiet low tone of speaking, and she resumed her reading at the table, without giving any sign of the storm of emotion she had just passed through.

The wretched woman seemed to have hardened her heart, and determined to maintain the strictest silence.

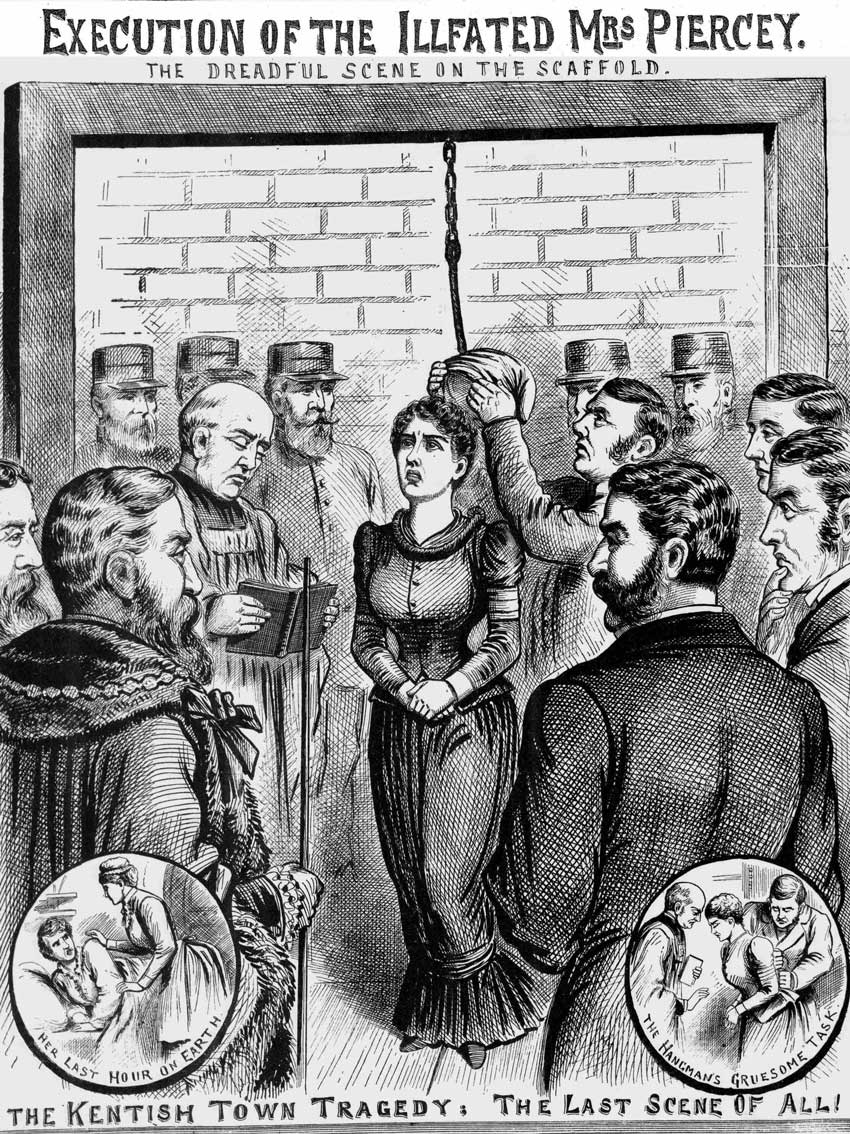

THE EXECUTION

The execution took place at eight o’clock on Tuesday morning [23rd December 1890].

Late on Monday evening, about half past nine o’clock, the condemned woman was removed from the cell in which she had been imprisoned into the condemned cell in the male wing, which is in close proximity to the execution shed.

Mrs. Pearcey was attended by three women warders, and on her way was in tolerably good spirits, but complaining of the dense fog.

Soon after 10 o’clock the Rev. Mr. Duffield, the chaplain, returned to the prison, and proceeded immediately to her cell.

I AM NOT GUILTY

He had an earnest conversation with her for rather more than half an hour, and urged her, “Do not be launched into eternity with anything on your mind which yo can now explain.”

She replied calmly but faintly, “I have nothing to explain, I am not guilty.”

HER LAST NIGHT

All day she had eaten very little, and when she went to rest, about half-past 11, she took no supper.

Her sleep was very disturbed – not half an hour of consecutive slumber dimmed her senses – and about half-past three she rose and dressed, and then asked for a cup of tea.

She ate nothing.

From that time she occupied her time in reading, now and then addressing a remark to her attendants, who were far more exercised at the terrible crisis than she was herself.

SHE AVOIDED THE SUBJECT OF THE MURDER

It was about six o’clock when the chaplain next visited her, and she received him in a languid manner, alway evading conversation on the subject of the murder.

The chaplain had hoped to have received from her at that trying moment some confession in regard to the part she bore, and in solemn words pointed out her position once more. He urged her to make some reparation to her fellow creatures by letting them know the truth, but all he could get from her was that it was absurd to suppose that Hogg was connected with it.

For more than an hour this painful interview was maintained, but no change was made in her obdurate contention that she was not guilty.

BREAKFAST AND PRAYERS, BUT NO CONFESSION

A little after seven o’clock he left, and her breakfast was brought in.

But she would not eat anything – merely drank a little tea.

Again, about half-past seven, the chaplain returned, and for some time engaged with her in prayer.

She was perfectly calm and she repeated the Lord’s Prayer with him in a quiet but distinctly audible voice.

Again and again he urged her to make her peace before the inevitable doom overtook her, but met with no response.

At length, just as the clock pointed to five minutes before the hour he said, “The foot of the executioner is almost at your door. Now I ask you, for the last time, is there anything you have to say to me?”

“No,” was her emphatic reply.

“Do you admit the justice of your sentence?”

“Yes; but the greater part of the evidence was false.”

“Then you mean to say by that that you are guilty?” asked Mr. Dufield, in anxious expectation of a reply.

But no reply came; she shook her head and sat down upon a form.

THE EXECUTION PARTY ARRIVES

After a word or two more of exhortation and sympathy, the chaplain left, and the officers of the law entered.

They consisted of Alderman Sir James Whitehead, Bart., High sheriff of the County of London; Mr. Metcalfe, his under sheriff ; Colonel Milman, governor of the gaol, and Berry, the executioner.

When she saw them she quietly rose from the form where she was sitting, and the female warders gathered round her.

“This is Berry,” whispered one.

“I know,” she replied, as she took his proffered hand.

SHE WAS PINIONED

Scarcely a word was said as she was pinioned – a work of only a few seconds’ duration.

Just before the pinioning she had some more tea, and in answer to Sir James Whitehead’s question as to whether she had anything to say, she replied in the negative.

She turned round to the female warders who have been her constant companions since her conviction, and calmly bade them “Goodbye” – not a tremor in her voice, and no trembling in her hands.

HER UNCOMPLAINING FORTITUDE

They, who during their enforced intercourse with her had grown to like her quiet submissive ways – her uncomplaining fortitude – were much affected, and, when Berry had completed his operations, two set out to walk with her, one on each side.

By a sign, however, she refused their aid, and walked alone and unsupported into the corridor.

Here were assembled certain other gentlemen who watched the procession pass in solemn silence.

It only went across the corridor into the exercise yard beyond.

THE WHITE CAP DRAWN OVER HER EYES

By another recent merciful modification, at this point the white cap was drawn over the prisoner’s eyes, so that she saw not the instrument of death.

Guided by Berry, the warders led her directly under the rope.

The shed was lighted by gas, and the front, which on occasions of execution is generally raised, remained closed.

The chaplain meanwhile had placed himself just in front of the wretched woman, reciting passages from the Burial service.

HER EXECUTION

When she arrived upon the drop, the female warders left her, and two male warders took their place while Berry fixed the rope.

Not a word was spoken after leaving the cell by the prisoner or anyone else; save the solemn phrases of the liturgy.

As soon as the strap was affixed round her dress, just below the knees, Berry touched the warders, who stepped back, then laying his hand on the lever he pressed it down, the floor opened, and Mary Eleanor Pearcey passed away almost instantaneously from sight.

Death must have been immediate, there was only the smallest vibration of the rope – which gave a drop of 6ft – and, as was given in evidence at the inquest, it resulted from dislocation of the vertebrae not from strangling.

EVIDENCE OF PAIN

None the less when, after an hour, she was taken down and laid in her coffin there was an unusual suffusion of blood visible under her delicate skin, and the purple hue of her lips, curled back and showing her prominent teeth, gave evidence of pain.

THE SCENE OUTSIDE

Those who had occasion to enter Newgate prison on this painful business found, long before half-past seven, the Old Bailey crowded with a dense throng of people – both men and women – who had come to receive a secondhand excitement by seeing the black flag run up at the entrance the moment of execution.

Not a word of sympathy was expressed for the culprit, who, especially by the women, was considered to have deserved her doom.

It is proper to say, on the authority of the chaplain himself, that he attaches little or no importance to the semi-confession made by the convict.

Remarkable as it may seem, women under sentence of death rarely, if ever, do confess, and in Pearcey’s case there would appear to have been other mysteries in connection with her life than that which has made her name notorious.”

THE ILLUSTRATED POLICE NEWS

In its issue of Saturday the 27th of December 1890, The Illustrated Police News provided a more detailed account of the scene outside the prison as the execution was taking place inside:-

“Despite a bitter frost, a sulphury fog, and slippery streets, small knots of people commenced gathering in the Old Bailey before seven o’clock on Tuesday morning to satisfy a morbid curiosity in seeing the black flag hoisted over the walls of Newgate Prison, a symbol to the world that Mrs, Pearcey had paid the penalty of the law for the atrocious murders of Mrs. Hogg and her infant child at Hampstead.

The solemn tolling of the dying woman’s funeral bell had no effect upon the crowd, not the slightest sympathy being felt by the members of her own sex.

At one minute before eight o’clock a yell from the crowd proclaimed the fact that the black flag was hoisted, and directly after the crowd gave vent to their feelings in a loud cheer, which was taken up and repeated as the scattered groups gathered into one compact mass in the Old Bailey.

Excited talk was general, and fierce delight was expressed when it was found that the unhappy creature had paid the penalty of her crime.”

THE CHAPLAIN’S HEALTH AFFECTED

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, continued its coverage of the execution by describing the visible effect the strain of it had had upon the countenance and the emotional well-being of the chaplain:-

“The constant ministrations of Mr. Duffield, and his intense anxiety to improve the spiritual condition of his prisoner, told upon his health and appearance in a most serious manner, and both at the execution and the inquest he looked extremely ill.

It is impossible to estimate the care and anxiety which such an office imposes upon a conscientious man.

HER BODY IN THE COFFIN

Those who, at the inquest, saw the body lying in the shell noticed not only the discolouration of the face already mentioned, but an expression of pain quite foreign to Mrs. Pearcey’s countenance during all the anxious days of the trial.

Her long luxuriantly curling hair was spread down her back and over her shoulders, her hands, outstretched and without any appearance of contortion, were at her side, and her feet, though denuded of boots, appeared small and well shaped.

She was dressed in the striped, stuff gown she wore at the trial, and, at the foot of the coffin, her boots were placed to be buried with her, since it is required that all persons executed should be buried in the clothes last worn by them.

There could be no doubt that the neck had been dislocated, for one of the jurymen moved the head about to ascertain the fact.

GREAT LUMPS OF LIME

Close observers could see that in the bottom of the plain deal coffin were great lumps of lime – while in the corner were two or three bags of the same material, which were to be emptied into the coffin before burial.

The lid had a large number of holes bored in it, and when it was fastened down several buckets of water were poured into it before it was taken to the place of burial.

This, as is well known to all who have visited Newgate, is in the passage-way leading from the gaol to the court.

As the jurymen entered the prison to view the body they passed by the already open grave, which was about 7ft. deep.

It is the same grave as was used for one Wiggins, who was executed in 1867 for the murder of Agnes Oaks, his paramour, at Limehouse.

When the ground was disturbed there was hardly a trace of his body discoverable.

Five bushels of lime were spread beneath the coffin, and the same quantity placed above it, the earth filled in, the flagstone relaid, and the spot marked with a “P.”

THE INQUEST VERDICT

Having viewed the body, lying in the shell on the floor of the scaffold beneath the beam, the jury at the inquest into her death returned their verdict that “they were satisfied that sentence had been executed upon Mary Eleanor Pearcey, and it was carried out in a proper manner.””

A BIZARRE AFTERMATH

Whilst the trial was still on-going, Madame Tussaud’s waxworks, spotting the opportunity afforded by the publicity and excitement being generated by the case, had secured many of the items that had been discussed at length in the court case.

According to Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper:-

“All the furniture from the prisoner’s lodging has been secured by Madame Tussaud’s, together with every object of interest made prominent at the trial.

Already there has been arranged a facsimile of Mrs. Pearcey’s sitting-room, complete with pictures, couch, and piano; in fact, every detail, even to the lace on the mantel border, being observed.

Mrs. Pearcey’s model figures as the centre of the group, represented standing up, with her hat hanging by a riband to her hand.

Adjoining this excellently executed group is the perambulator – sold to Messrs. Tussaud by the man Hogg – and its fixings, including the nut found; the prisoner’s jacket, worn on the day of the murder, models of the heads of the victims, and the piece of toffee which the murdered baby had been sucking.

Preparations are being made to show the kitchen (the scene of the murder), the bedroom, and a tableau representing the Hogg family at home.”

Indeed, so eager was the waxwork’s to jump on the bandwagon of the publicity generated by the trial and execution of Mary Pearcey that, by the end of the month, adverts for their new attraction had begun appearing in the newspapers.

THE END OF THE AFFAIR

Thus ended a saga that, since October 1890, had captivated the Victorian public’s imagination.

Frank Hogg soon faded from the limelight, and it has never been established what happened to him once his mistress, and the murderess of his wife and daughter, had been executed.

Given his unpopularity with the public at large, he may well have used the money paid to him by Madame Tussaud’s to start a new life elsewhere, possibly in America.

Notwithstanding the police and newspapers at the time dismissing the murder as having anything to do with the Whitehcapel murders, Mary Pearcey’s name has, perhaps inevitably, still managed to end up on the ever growing list of Jack the Ripper suspects, although the majority of serious scholars of the case lend her candidacy little credence.

It would appear that she murdered Phoebe Hogg in a fit of rage, possibly following an altercation over her relationship with Phoebe’s husband, Frank.

The baby, it would appear, was suffocated by the weight of her mother’s body, which Mary Pearcey placed on top of her in the perambulator in order to transport her away from the scene of the crime.

The mysterious advert that Mary Pearcey had her solicitor place in a Madrid newspaper has never been explained.

Indeed, the only thing that can be said with any degree of certainty is that, with the execution of Mary Pearcey, on the 23rd of December 1890, a sad, sordid and tragic case, at the heart of which lay a murdered mother and child, came to gruesome conclusion.